“We do not create anything, we have intuitions.”

— An interview with Piero Castiglioni

When we arrive to meet with Piero Castiglioni in Milan, we notice the architect in the street in front of his studio, dressed in a long brown wax coat and smoking a cigar. He accompanies us across the courtyard and, with a noticeably springy step, walks down the stairs to the studio where we are greeted warmly by his collaborators and his dog, the Rhodesian Ridgeback Simba, who jumps at us happily. We spot scale models of famous lighting projects, like those of the Musée d’Orsay and the Church of the Savior on Spilled Blood in St. Petersburg, and many lighting models on the ceiling.

Castiglioni leads the way to his room filled with ever more lighting models, awards and which has a wall with radio models by his father Livio, and offers us a seat. He sits down with his inseparable Cuban cigar—which regularly goes out and which he then enthusiastically lights again—looking at us kindly. The following interview has been translated from Italian.

-

I would like to start with the studio where we are now, because you have been working here for a long time. It has a long history, doesn’t it?

“Lunghissima… [laughs]. In this studio I have worked since 1972, so I started working here fifty-two years ago. First with my father [Livio Castiglioni—Palainco], who already had his studio here. He also worked here with his brothers, with the other two architects, Pier Giacomo and Achille. Later my father and I got together after I had graduated, and I had started working on my own. It happened when I did “Italy: The New Domestic Landscape” in New York [at MoMa—Palainco], where I was doing the audio-visual lighting part for Ugo La Pietra. My father was working there as well, initially for Joe Colombo, but since he had died shortly before, he was collaborating with his brother Gianni.

And there we met. He said: ‘You do the same things that I do, let’s work together.’ ‘Well, let’s see…’ I said. ‘You do your jobs, I do mine, and every now and then we do something together’, he proposed.

But working in the family is by no means easy, so I reluctantly said: ‘Okay, let’s try it.’ And after six months I had no more projects of my own, and neither did he, because we had found our form of communication.” -

Piero Castiglioni in his studio in Milan. (Picture by Palainco)

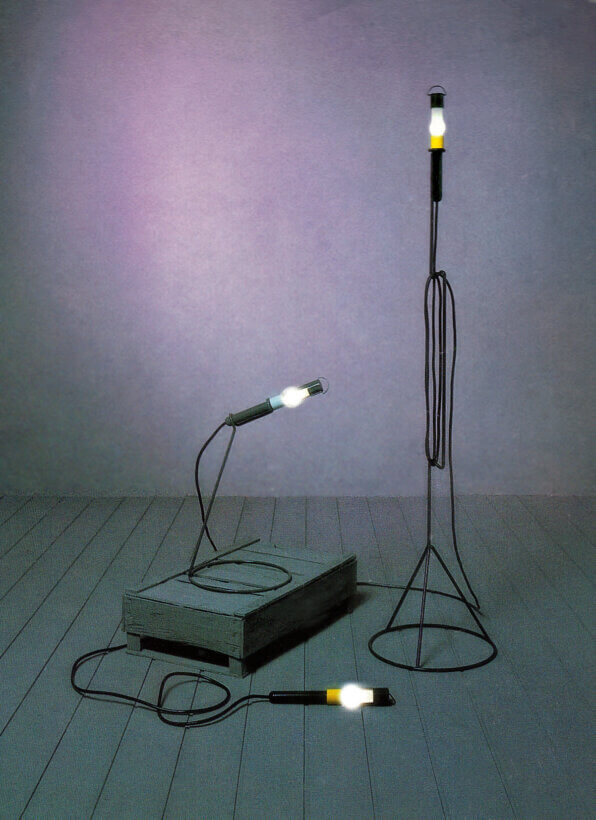

Below: Scintilla AT1F300, designed by Livio and Piero Castiglioni in 1972 and produced by Fontana Arte. (Picture ©Studio Piero Castiglioni)

Piero Castiglioni in his studio in Milan. (Picture by Palainco)

Below: Scintilla AT1F300, designed by Livio and Piero Castiglioni in 1972 and produced by Fontana Arte. (Picture ©Studio Piero Castiglioni)

-

-

“With my father there was great harmony, and from working together there was born what later would become the Scintilla system. It was a bit of a revolutionary idea: to dismantle the lighting fixture and leave the light source naked. You see them over there [he points at the ceiling, where two early Scintilla prototypes are mounted perpendicular to each other]. And to make it so, that the environment becomes the lighting fixture. Because there is a direct light, which makes these waves, but light is also reflected by the walls and like that, the environment becomes the lighting fixture.

The first time we used them was in an art gallery in a historic palazzo, all frescoed. He said: ‘You can’t put up devices, let’s put in naked halogens, because they don’t interfere with the space in an invasive way as they are very light.’ We started like this, and then after that I did showrooms and private houses.”

Were they easy to apply in different kinds of spaces?

“Yes, you just needed to bring the wire and connect it. It was this thing of going against the trend by not making a lighting device as such, a lamp. It was revolutionary, in fact. There were those times when I went against the grain.

However, since I did many things and couldn’t follow the production—because initially we produced them ourselves—I had to hand it over to Fontana Arte and I could continue to do other things.”“I almost never sit down at a table to invent something.”

Today we mainly do lighting projects and every now and then we do some design projects. I almost never sit down at a table to invent something; normally a design project is done when I’m in the field, at a job, and I can’t find a lamp that is suitable. Well, then I design it and I have it produced.”

On the seemingly endless list of lighting projects that Piero Castiglioni developed for buildings, museums, urban spaces and exhibitions one can find many important projects, like the Roman Forum, the Sistine Chapel, The Uffizi in Florence and the Centre Pompidou, but also the city of Ahvaz in Iran.

“I’m only missing one continent: Antarctica. We have worked in Brazil, in the United States, in all of Europe, China, Japan, Mexico. I have done fifty-two museums alone, all over the world. I have worked with ten Pritzker laureates, without considering also the competitions that we still do.”

-

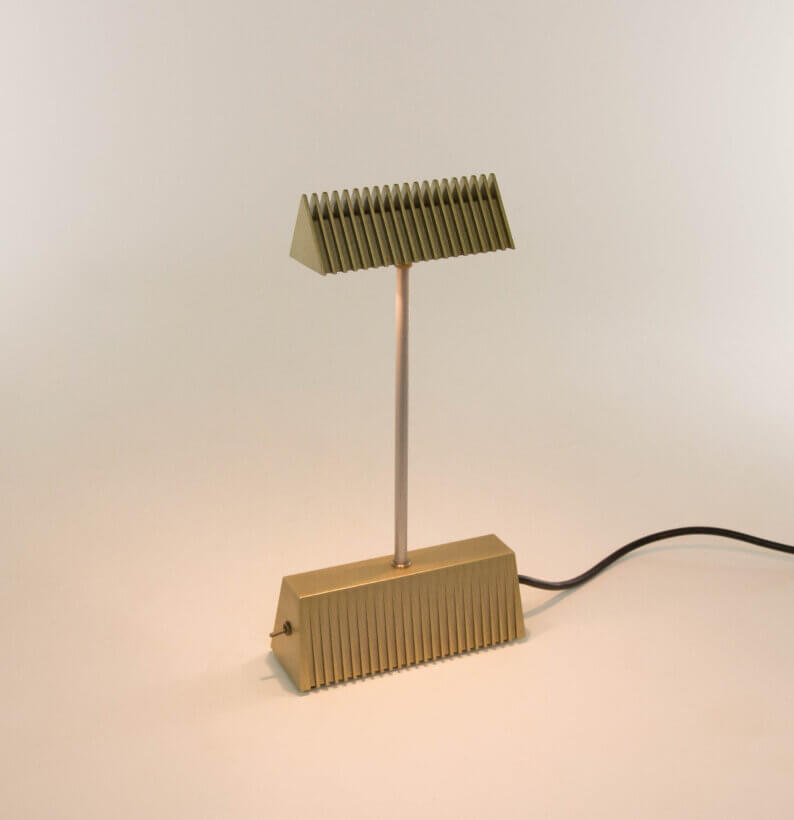

Minibox table lamp, designed by Piero Castiglioni with Gae Aulenti for Stilnovo in 1981. (Picture by Palainco)

Minibox table lamp, designed by Piero Castiglioni with Gae Aulenti for Stilnovo in 1981. (Picture by Palainco)

-

How do you take on lighting projects like these, that involve great responsibilities and real challenges?

[He lights his cigar again.]

“Well, the biggest challenge was that of Musée d’Orsay, because when Gae Aulenti and I tackled the theme I had already teamed up with her in the competition. And when we won, she and the chief curator of the museum told me: ‘Be careful, this is a train station that we have to transform into a museum, which is already a very complicated thing. There’s the architecture, and there are some very important works. That’s it. We don’t want to see any light bulbs, and we don’t want to see any light fixtures.’ And at the time it was very difficult. Working with Aulenti I made sure that the architecture became the light fixture. At d’Orsay you couldn’t even see a light bulb, not even a fixture. There was the light that was always mediated by indirect light controlled from the vaults and the niches.”

-

Piero Castiglioni working in Musée d’Orsay in 1983. (Picture ©Studio Piero Castiglioni)

Piero Castiglioni working in Musée d’Orsay in 1983. (Picture ©Studio Piero Castiglioni)

-

Had this been done before?

“It was completely new. And also the light sources that were used. For technical reasons we had a very low standard: fifty watts per square meter, in such a large environment. We had to use discharge lamps as we couldn’t use halogens. Instead we used fluorescent metal halide lamps that always have problems with light, because it always tends towards green. We had to correct it with the architecture. Working on the colour triangle we had found a complementary colour. There was a small amount of pigment in the paints on the walls that had to reflect the light that was close to purple to lower the green. And this made the light turn out white. I did a huge job, it was six years of work; twenty thousand square meters and each area had to be treated.”

How did you know these things? Or did you have to invent everything?

“Well in Italy in the 1970s—when we started with Scintilla—and also in the 1980s, there was no lighting technology. Plant engineers made the projects, also designing the elevators and the air conditioning. There was no specific knowledge regarding lighting and so I had to study to teach myself, even all the photometry.”

But apparently you were very open to discovering these things?

“Exactly, yes. And still today, that is… you always need to have the desire to study. And so today I still study.”

-

A part of Musée d'Orsay in Paris, illuminated with the light fixtures out of sight. Model in 1:10 scale, in Piero Castiglioni’s studio. (Picture ©Studio Piero Castiglioni)

A part of Musée d'Orsay in Paris, illuminated with the light fixtures out of sight. Model in 1:10 scale, in Piero Castiglioni’s studio. (Picture ©Studio Piero Castiglioni)

Piero Castiglioni explains how he managed to illuminate the paintings and walls in Musée d'Orsay evenly and without creating reflections. (Picture by Palainco)

Piero Castiglioni explains how he managed to illuminate the paintings and walls in Musée d'Orsay evenly and without creating reflections. (Picture by Palainco)

-

You needed to hide light fixtures in Musée d’Orsay, but you also designed fixtures that were in sight, like Minibox.

“Yes, we used Minibox, because in some cases, in small rooms, it was not possible to illuminate with that system. [He gets up and fetches a Minibox table lamp and puts it on the table in front of us.] This was the idea. They were placed on some—not tracks—but iron surfaces, and with the magnet that you see here you could orient them. They were not like the lamps mounted on tracks, the ones you always see, that look like lots of hanging salamis [we laugh]. You see, it has a sphere that works with a magnet, and since the halogen lamp would heat up, you had to be careful or you would burn yourself if you were to orient it. In the small rooms of d’Orsay they were mounted on the wall or on the ceiling depending on the situation. And later we also made a table model.”

How did you work on the project with Gae Aulenti, I suppose that you always had to confer, since you always had to know what the other was doing?

“Well, I claim that—and I also talked with her [Gae Aulenti—Palainco] about it—projects always arise from literature. So, let’s dive into a broader story…

Man became Homo sapiens when he began to speak and could exchange information. Then with the advent of writing, the information could remain. And so, language is very important. Vico Magistretti, who was a great friend, said that he did his best projects not with a pencil, but by telephone. There is great truth in that, because by talking we manage to keep some concepts in our brain that must remain abstract for a while. I have transmitted many of my projects by telephone. Later you pick up a pencil and start developing. A project always arose from a discussion between me and Aulenti, so we talked a lot. I knew Gae Aulenti even before my father did, because she was my assistant at university. So yeah, I had that kind of relationship with her.”

“Our work as designers is a servant’s work, we are like waiters.”

Is it safe to say you have learned to highlight the work of others with your work?

“I have always maintained that our work as designers is the work of servants. We are like waiters; we must provide good service.”

[After we look at him doubtfully…]

“Maybe not exactly… let’s say butlers, let’s say that we do a little bit more, but anyway it’s a service job. We must provide a service to the client, to the curator, to the architect, and in this case to La Aulenti. But above all to the works, because they must be well preserved and also to the public, because the public must see them well. It’s a whole set of services that we must give, like a good waiter. Yes, therein lies the satisfaction of the waiter. And when the client, the public and the architect are happy with the work, the waiter has provided a good service and should be satisfied.”

-

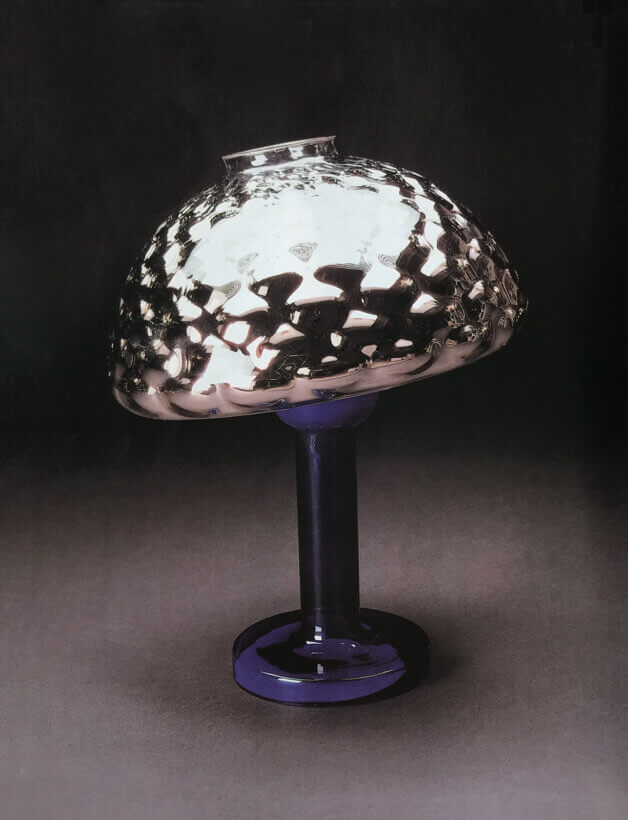

Parola table lamp, designed by Piero Castiglioni with Gae Aulenti for Fontana Arte in 1980. The diffuser was available in light blue, amber, pink and white coloured glass. (Picture ©Studio Piero Castiglioni)

Parola table lamp, designed by Piero Castiglioni with Gae Aulenti for Fontana Arte in 1980. The diffuser was available in light blue, amber, pink and white coloured glass. (Picture ©Studio Piero Castiglioni)

-

In the 1980s you also started to make models for Fontana Arte, for instance Parola.

“La Gae, who had just become artistic director at Fontana Arte, said: ‘We need to design a table lamp’. Since Fontana Arte uses glass a lot, I said: ‘I know three glass technologies: one is glass in sheet, one is the Pyrex glass that we also used for our naked halogens and then there is Murano glass.’ We used all three of them for Parola. The sphere is Murano glass, the stem is Pyrex, which is very resistant, and the base is sheet glass. We didn’t put in anything metallic, so that was already my first idea. Then there was a second idea; we said: ‘Inside the cable will be visible, but we can’t use a plastic cable.’ Instead we used a fabric cable, the kind that is also used for an iron. A fabric cable gives the lamp its nobility, its richness. That’s the idea.”

And the form?

“La Gae said: ‘Let’s make a sphere with a cut so that direct light comes out.’ And there is also the immediate light from the glass, so Parola was born like this. And then we also made it into a floor and a wall lamp.”

-

The Edy series, designed by Piero Castiglioni for Fontana Arte in 1982. Edy was born as a wall lamp when Castiglioni was working on a project for which he needed to illuminate a large portico. It consists of a metal painted structure, with a natural transparent glass diffuser. With a series of accessories it can be installed on the floor, on a table, on the wall or suspended. (Picture ©Studio Piero Castiglioni)

The Edy series, designed by Piero Castiglioni for Fontana Arte in 1982. Edy was born as a wall lamp when Castiglioni was working on a project for which he needed to illuminate a large portico. It consists of a metal painted structure, with a natural transparent glass diffuser. With a series of accessories it can be installed on the floor, on a table, on the wall or suspended. (Picture ©Studio Piero Castiglioni)

-

Drawings of Edy by Piero Castiglioni. (Picture ©Studio Piero Castiglioni)

Drawings of Edy by Piero Castiglioni. (Picture ©Studio Piero Castiglioni)

“Edy is one of the models that I did by myself. I wanted a waterproof lamp, in fact I made an underwater picture at the time of myself with the lamp, because it could be completely immersed in water. The idea was a waterproof lamp that needed to have various functions, with a shade to direct the light, or just naked.”

Was it mainly meant for outdoor use?

“Yes, but I have the lamp at home on my bedside table, and if I want, I can detach it from the support, put it near a book to see better, and then I hang it back.” [Laughs]

-

We like it a lot. We have already asked ourselves why the wire is about ten metres long.

“I needed outdoor lamps for a project, and I wanted to put on some lamps like they did in the past, when they used torches. Edy is like a miniature torch with a halogen bulb. We needed to illuminate a large portico [starts to draw a portico]. We put these torches here; it was born like this. At first it had this function, on its support on the wall with its cable leaving the cable pass going to the sockets that were low on the wall, almost on the floor. Later we did the version with the shade to direct the light, as well as a pendant and a floor lamp.”

[He lights his cigar again.]

Do you remember when you first realised that the objects and the buildings around you were designed by man?

“Well, man is present everywhere, but there is one thing, which is that when we talk about ‘man’ we talk about artifice, artificial, because man makes artefacts. I maintain that the words ‘natural’ and ‘artificial’ are not in contradiction, but they coexist. Is a bird’s nest artificial or natural? It is both, if one must give an answer. Because we too… man is part of nature. When one talks about artificial light there is a bit of a sense of putting it in second place, as if everything that is natural is best. However, natural light does not exist, because if I turn off the lights here, we have a light that comes through the windows, but the windows are again an artefact. That is, even the light that is called ‘natural’, when it enters a building, is an artificial light, because it is always mediated by architecture. And at the same time an artificial light can also be natural, because man is part of nature.”

“I never talk about creativity, but about intuition.”

When did you understand that man could create all these things?

“Man does not create anything. Those who call themselves ‘creative’ in my opinion are just imbeciles, because we cannot create. If there is someone who creates, it’s that that gentleman up there [points upwards]. We do not create anything, we have intuitions, which is different. In fact, I never talk about creativity but about intuition.”

That is beautiful!

“It’s right. We have intuitions, and intuitions come from observation. I always say to young people that learning to observe helps to imagine.”

-

‘I Castiglioni': Piero Castiglioni with his father, cousin and uncles in Achille and Pier Giacomo’s studio at Piazza Castello in Milan in 1968. From left to right: Achille, Livio, Giorgina, Pier Giacomo and Piero Castiglioni. (Picture Ugo Mulas ©Ugo Mulas Heirs. All rights reserved)

‘I Castiglioni': Piero Castiglioni with his father, cousin and uncles in Achille and Pier Giacomo’s studio at Piazza Castello in Milan in 1968. From left to right: Achille, Livio, Giorgina, Pier Giacomo and Piero Castiglioni. (Picture Ugo Mulas ©Ugo Mulas Heirs. All rights reserved)

-

When did you understand that it worked like this, already at a young age?

“By working. I come from a family… My grandfather was a sculptor, an important sculptor [Giannino Castiglioni—Palainco]. He made a door for the Duomo di Milano. He did a lot, and I also learned from my uncles [Achille and Pier Giacomo Castiglioni—Palainco] and from my father [Livio Castiglioni—Palainco]. That is, we chewed over the meaning of architecture—never art—because even my grandfather wasn’t an artist. A great sculptor yes, but he always worked on commission, while an artist sits down and invents something. My grandfather was a craftsman and all things considered my uncles and my father were also craftsmen.”

When you were young did you see all these things that they did?

“Sure. My grandfather, being a sculptor, worked with sculpture moulders; those who made the plaster casts. My uncles and my father in turn used the people my grandfather worked with. At the time there was no three-dimensional design yet, but to make their shapes, their objects, they used the sculpture moulders of my grandfather’s. So, the artisanal contribution was very important.

I also learned another thing from them that is very important. They always had fun, that is, in my father’s studio and that of my uncles there were more toys than at home. I went to the studio to play because they played while they were working. They did serious things while having fun, while many architects do ridiculous things in a serious way instead. And also here we always have fun.”

-

Livio e Piero Castiglioni reflected in a silvered bulb in their studio in Milan in 1975. (Picture ©Studio Piero Castiglioni)

Livio e Piero Castiglioni reflected in a silvered bulb in their studio in Milan in 1975. (Picture ©Studio Piero Castiglioni)

-

At a certain point you decided to study architecture, just like your father and uncles…

“I already hashed it out with the family, so it was my path. In my family we chatted and made fun… In those years—I’m talking about the 1960s—there was a lot of friendship between architects. In my house Magistretti and Zanuso always passed by, and so I was familiar not only with the architecture of my father and my uncles, but also with the work of others who came by. There was great harmony back then among architects, there was no rivalry, let’s say.”

And when you started studying architecture you already knew a lot, much more than others probably?

“Yes, I had that advantage, but then it also was a disadvantage because starting with a family of illustrious architects it is very difficult to keep up with them. I had to keep up with those who preceded me in the family, but I think I succeeded a little. [He laughs a modest laugh.]

Besides, I have always had the desire to learn. I have worked with I-don’t-know-how-many architects, I could say maybe even a thousand. Among them ten Pritzker laureates, but I have also worked with small provincial architects. I have always given them all the support that I could give, like a waiter, but I learned a lot of things from them as well, because every architect has his own way of thinking and working. I learned a lot of things from Renzo Piano, and others.”

They also learned from you, probably.

“Yes, there is an exchange.”

-

Cestello, designed by Piero Castiglioni with Gae Aulenti for Palazzo Grassi in Venice in 1986. Cestello was later produced by iGuzzini. (Picture ©Studio Piero Castiglioni)

Cestello, designed by Piero Castiglioni with Gae Aulenti for Palazzo Grassi in Venice in 1986. Cestello was later produced by iGuzzini. (Picture ©Studio Piero Castiglioni)

-

Cestello light fixtures, in the 18th century Palazzo Grassi in Venice, that was transformed into a cultural centre. As the lighting equipment could not be mounted onto the decorated ceilings, nor on the walls or placed on the floor, they were fixed into the added plasterboard walls. (Picture ©Studio Piero Castiglioni)

Cestello light fixtures, in the 18th century Palazzo Grassi in Venice, that was transformed into a cultural centre. As the lighting equipment could not be mounted onto the decorated ceilings, nor on the walls or placed on the floor, they were fixed into the added plasterboard walls. (Picture ©Studio Piero Castiglioni)

-

For Palazzo Grassi in Venice, an 18th century palazzo, you designed the Cestello lamp.

“Yes, we used these lamps, which later would become a bestseller when they were produced by Guzzini. They have copied them all over the world. Palazzo Grassi is a centuries old palazzo that was transformed to house temporary exhibitions. The floors are decorated, and there are decorated ceilings. I worked there with Aulenti. She said: ‘We can’t touch the floors, we can’t touch the ceilings, we only have the walls at our disposal.’

The walls in Venice in these buildings were always covered in fabric because all the humidity from the canals pulled up from the walls. The Superintendency gave us the possibility of making a second wall that contains all the technology of the building.

And with dialogue, like always with dialogue, ideas come out. Speaking with Aulenti I said: ‘Let’s make some batteries of lamps that are orientable. You know, like those baskets used for bottles of water or wine. Let’s make a basket like that. In fact, the lamp was called Cestello [in English: basket—Palainco].

The lamps in the device can be oriented individually. In the rooms of Palazzo Grassi you can see all the devices positioned. We did many calculations, because it’s not easy to get a uniform light on the walls.

Like I said, Palazzo Grassi is a building for temporary exhibitions, with possibly delicate objects, like drawings. The Cestello lamp has five different types of ignitions within each device. This means that a group of lamps was used to give homogeneity on the wall. You could have an ignition for paintings, one for drawings, a third ignition to illuminate decorated ceilings, a fourth ignition that was not constrained by studied angles but was constrained by objects that could be in the centre of the area and the fifth was the emergency one. I did thirty-five temporary exhibitions in Palazzo Grassi.”

-

Scintilla table lamp, designed by Piero Castiglioni for Fontana Arte in 1984. Structure in die-cast anodised aluminium with a built-in transformer. “I couldn't put a naked lamp on a table, and so we made this triangular little hat like a Toblerone chocolate, which had to dissipate the heat of the two halogens that were inside.” (Picture by Palainco)

Scintilla table lamp, designed by Piero Castiglioni for Fontana Arte in 1984. Structure in die-cast anodised aluminium with a built-in transformer. “I couldn't put a naked lamp on a table, and so we made this triangular little hat like a Toblerone chocolate, which had to dissipate the heat of the two halogens that were inside.” (Picture by Palainco)

-

Let’s return to the studio. As you said earlier, you have been working here for such a long time. What does this place mean to you?

“I am fond of it. Here my father, in the beginning, designed many radios. We work like this, there aren’t many of us, just five in total.

[He lights his cigar again.]

There’s something that is important to know, and that not many people know of, which is that the studio was founded by my father and Luigi Caccia Dominioni, who were schoolmates. Six months later, Pier Giacomo graduated and entered the studio. And five years later Achille also joined. Before the war my father had designed many radios together with Gigi Caccia Dominioni and Pier Giacomo. My father was also a radio amateur, so he was passionate about radios [gets up and points out some fantastic radios displayed on the wall].

After the war Phonola, who also made the radio that you see over there, asked my father to become a permanent consultant for them and offered him a dream salary. So my father told me and he abandoned the studio to work for them. He continued to work with his brothers in the evening, always contributing with his ideas, but the studio went on with Achille and Pier Giacomo. Gigi Caccia, who was linked to my father, had also left after my father did. At the time I was too young, and I never met Gigi Caccia.

Until the 1980s, when I was called to do the lighting for an exhibition at the Castello Sforzesco about Ratti [Antonio Ratti—Palainco], the one who made those great silks. And there I met Gigi Caccia and we started to work together on this exhibition.

Afterwards we continued to work together, Gigi Caccia and I, and he became a great friend. This was after the relationship with my father, because he had already died. My father abandoned him practically immediately after the war and I found him again forty years later. Gigi Caccia died at more than a hundred years old. He was another great architect, not very much esteemed, because Italian architects are all left-wing and he wasn’t. Therefore he was a bit mistreated. Even at university they never talked about Gigi Caccia, but I think he was a great architect. He also did a lot with design, and he founded Azucena. So this is another particular episode.”

-

Nina table lamp, designed by Piero Castiglioni and Gae Aulenti for Fontana Arte in 1981. The base and stem are made of a single piece of cobalt blue glass, and the adjustable shade is made of silvered optical glass. (Picture from a 1999 Fontana Arte catalogue, from the Palainco archive.)

Nina table lamp, designed by Piero Castiglioni and Gae Aulenti for Fontana Arte in 1981. The base and stem are made of a single piece of cobalt blue glass, and the adjustable shade is made of silvered optical glass. (Picture from a 1999 Fontana Arte catalogue, from the Palainco archive.)

-

Nina was another model that you did for Fontana Arte.

“Nina was a lamp in blown glass, but Austrian glass. The Austrians also know how to work glass well and above all they had this possibility to silver the interior of the glass to create the reflector. We made this lamp that could be tilted. We said: ‘Let’s make the stem in cobalt blue glass.’

The idea was to make a table lamp with a diffused light and instead of using a lampshade we used this technique that is used for Dewar vessels, making thermos jars. You can orient the screen. And it gave a beautiful light.” -

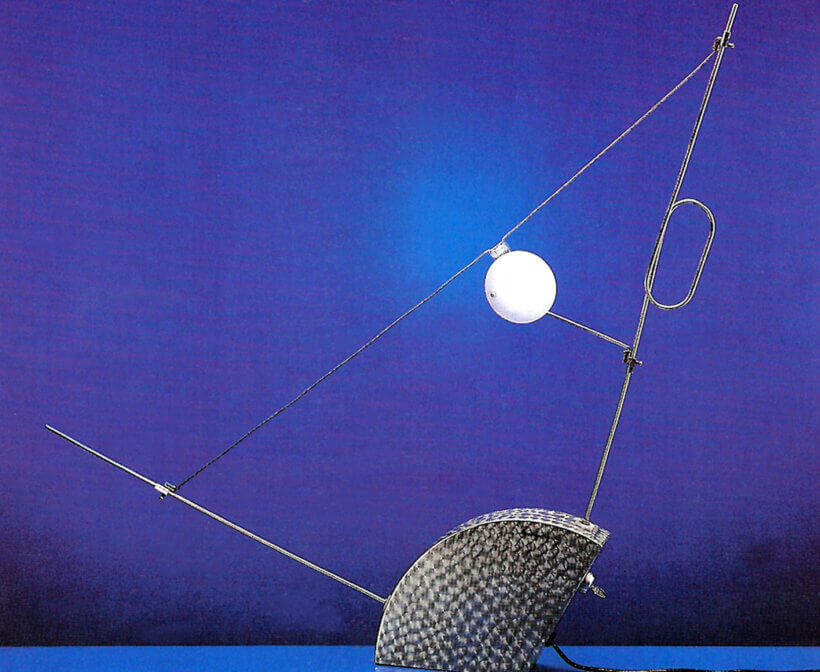

Econolume table lamp with key switch, designed by Piero Castiglioni for Il Mobile Infinito by Alchimia in 1981. The transformer is built in the steel base, conductor sticks are in chromium-plated copper, with silver chains and anti-dazzling screen in Pyrex sanded glass. (Picture ©Studio Piero Castiglioni)

Econolume table lamp with key switch, designed by Piero Castiglioni for Il Mobile Infinito by Alchimia in 1981. The transformer is built in the steel base, conductor sticks are in chromium-plated copper, with silver chains and anti-dazzling screen in Pyrex sanded glass. (Picture ©Studio Piero Castiglioni)

-

Your table lamp Econolume seems more like a work of art.

“Yes, a sculpture. A bit like the works of Ingo Maurer, it’s more poetic.

It’s a lamp that I made for Alessandro Mendini for il Mobile Infinito, in three copies only.“Do you know where they ended up?

“Well, Ennio Brion, the one from Brionvega, wanted to buy one, and he still has it. One of my architect friends from Umbria liked it, and I gave one to them. And the third one I kept, because I wanted to have one myself. Then Studio Alchimia did an exhibition of il Mobile Infinito, and I lent it to them. Alchimia went bankrupt, but although it was my lamp I could not get it back. There was no way, I even sued, but nothing could be done. It disappeared.”

Oh no! What a shame!

[He looks at a picture of Econolume.]

“These things happen. This lamp was born in the 1980s, when the energy saving lamps and mini fluorescent lamps came about. I always hated them, because they produced an ugly light and they were expensive. However, it seemed that with that light one could save the planet, which isn’t true.

So, this lamp here has a key switch, which saves energy [laughs]. I said: ‘To save energy let’s put a key to switch it on, and we will make a big saving.’ It was a point of contention.”Are the relationships between light and architecture and light and man always important to you?

“Exactly, and where there is art, you also must do a service to art. Especially today with outdoor lighting, light has become an architectural material, like iron and glass. Glass is a material one doesn’t see because it is transparent, but it is a material that is used. The same goes for light, which is not a matter, but it can be seen, it’s there. It’s an architectural material like iron, like brick, like cement.”

-

Piero Castiglioni working in his studio with the wall display with the radios designed by his father, Livio. (Picture ©Studio Piero Castiglioni)

Piero Castiglioni working in his studio with the wall display with the radios designed by his father, Livio. (Picture ©Studio Piero Castiglioni)

-

“LED lamps are a great transformation. I maintain that the LEDs have killed the device, they are killers. That is, killers of a certain type of light fixture. In technical devices, design is finished because the LED is either a punctiform light with a refractor to widen the beam, tighten it and adjust it. The LED can be a point, a line, or a surface, that’s it. The device no longer exists. In fact, everyone who produces technical LED lamps does the same thing.

But what is saved is the decorative lamp. [He gets up and walks to the wall where the radios that Livio Castiglioni designed are displayed.] Look at what happened with those radios… There are valves inside that heat up, transformers, resistors. These are all three-dimensional objects. Then look what happens: technology changes cultural models. [He points at a later, flat model by Bang & Olufsen.] That one is no longer a three-dimensional object, it’s a two-dimensional graphic object, because the technology killed a dimension. When the transistors arrived, the radio became a graphic object, not a design object.

And then the chip arrived. The chip is even smaller than the transistor. So where is the radio? We have it here [picks up his iPhone]. Who buys a radio today? It no longer exists, it is dead.”And what will happen to the lamps that you made, and to those that your uncles made?

“Many of them are decorative lamps. Arco [by Achille and Pier Giacomo Castiglioni—Palainco] is a functional lamp, but it’s also decorative. The base in marble, the stem, the reflector. That type of lamp will live forever. And also that one [points at the Tizio table lamp by Richard Sapper] will live on forever.

“Intuition happens by observing.”

How can you have dedicated almost your entire life to lighting? Do you get tired of it sometimes?

“No, no, I’ve always had fun. You must have fun with the things that you do, otherwise… I still have fun today.”

Do you work every day?

“I work every day. I’m eighty years old, but I’m still working.

We always have new themes, and like Rogers [Ernesto Nathan Rogers—Palainco] said: ‘Architecture goes from the spoon to the city.’ For us it’s the same, that is: we do things, from a small display case to the lighting of a city, like Ahwaz in Iran for example. Besides, the change of scale helps the imagination a lot; being able to think on different scales.In the courtyard there are some pots with clovers. I often go outside and while smoking my cigar, I have found four-leaf clovers. It’s precisely like that. Learning to observe helps to imagine, and observation is also a bit like looking for a four-leaf clover. Last year I found sixty of them, this year only one. No one thinks of clovers, they all seem the same, but there is always a four-leaf clover. You just need to find it, but it’s very difficult.”

Are you saying that one must always have an open mind and use their intuition?

“Exactly. Intuition happens by observing, and if one observes then one opens a dialogue; one observes and maintains a back-and-forth, and then the result arrives. That’s how it is.”

-

- Palainco wishes to thank: Maestro Piero Castiglioni for his warm welcome and for generously sharing his passion and insight into lighting.

- We would also like to thank: Viola Fumagalli, for her kind support.

Unless otherwise stated, all material is sourced and/or generated internally. All rights reserved.

- Text: Palainco, Koos Logger & Ingrid Stadler.

- Image sources: Courtesy of Studio Piero Castiglioni, Ugo Mulas Heirs and Palainco: Koos Logger & Ingrid Stadler.

The article and its contents may not be copied or reproduced in any part or form without the prior written permission of the copyright holders.

Published on: 15 September 2025