“I made millions of holes…”

Ugo La Pietra on his life's journey and incredible lighting pieces: “I don’t understand anything. I must understand through my own personal journey.”

We meet Ugo La Pietra in his spacious studio in Milan, filled from floor to ceiling with his works: paintings, ceramics, furniture, prototypes and books.

As an artist, filmmaker, editor, musician, cartoonist, teacher and formally architect by training, Ugo La Pietra so far managed to work bypassing rules and systems. Two Arcangeli rise above us. A small Globo Tissurato sits on a cupboard, a larger one sits on the floor. Some other lamps in methacrylate are scattered around, within reach. The following interview was translated from Italian.

-

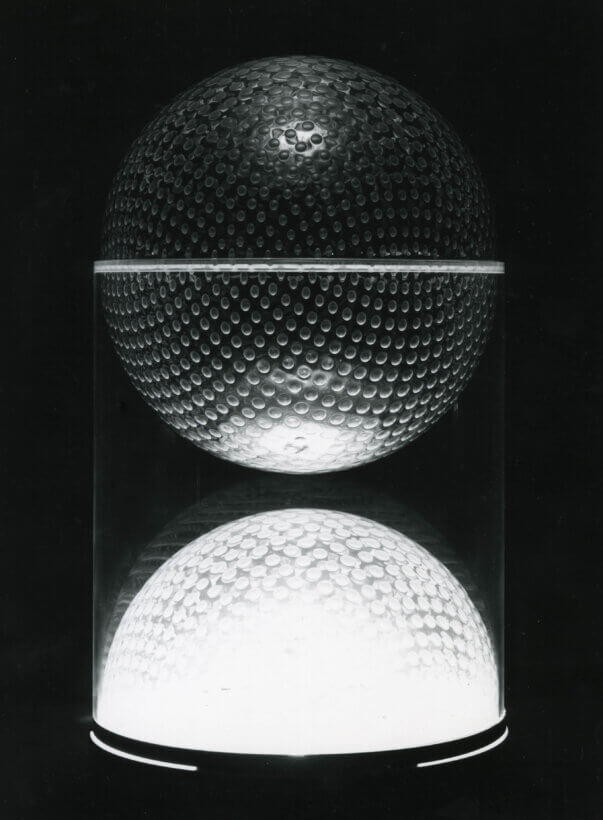

Globo Tissurato was the first lamp that you made, but it was an instant hit, wasn’t it?

“Yes, it was importantissimo, because it was published in Domus, and the day after it was published the greatest gallery owner in the world, a certain Iolas [Alexander Iolas, who had galleries in New York, Geneva, Paris, Milan, Zurich, Madrid and Rome] opened a gallery in Milan and said: ‘I want this gallery all lit up by these lamps’ —a particular effect. He let me do the job, and since it worked out very well, he was happy and he began to tell everyone he knew, all of them billionaires: ‘This La Pietra makes lighting.’ And so I’ve done work for Aga Khan and many great collectors, all thanks to this lamp here.”

-

-

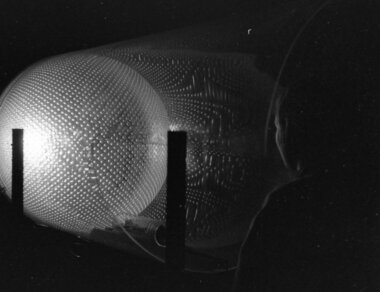

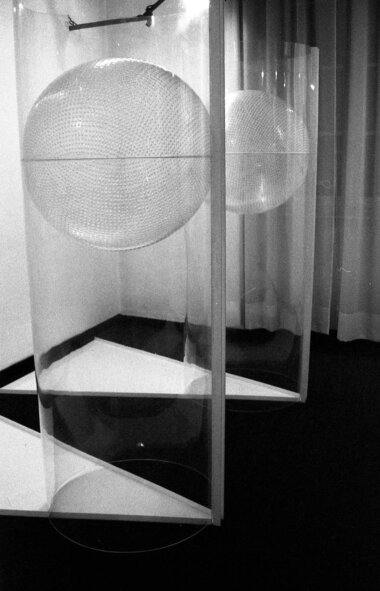

Far above: Ugo La Pietra with his Globo Tissurato lamp in 1967. Above and right: Globo Tissurato at Galleria Cadario in Milan in 1969. Pictures courtesy Archivio Ugo La Pietra.

Far above: Ugo La Pietra with his Globo Tissurato lamp in 1967. Above and right: Globo Tissurato at Galleria Cadario in Milan in 1969. Pictures courtesy Archivio Ugo La Pietra.

-

Do you consider the lamps that you made part of your oeuvre?

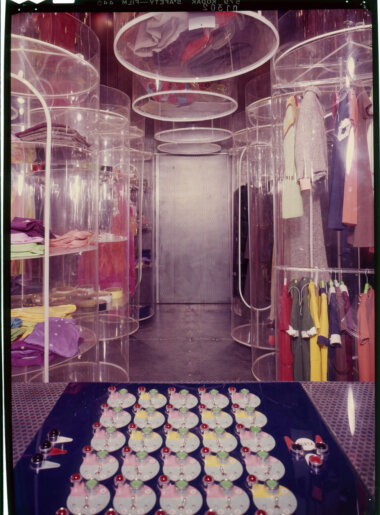

“Especially those in methacrylate are part of my work, mostly because of my relationship with craftsmanship. I made them in a very small company. I had a friend, Michele Moro, who died last year of Covid, poverino. I worked with him, we did everything together, for years. Small things, but also large things, fittings, like these here, very important ones for Mila Schön, a very beautiful shop [in Rome—Palainco]. We have done many things. We did this shop, everything with methacrylate sheets [shows pictures]. Do you see these sheets here, they are big, aren’t they? They all have little dead holes in them. I have done them one by one with a drill, by hand.”

Wow!

[He laughs at our surprise] “Haha, all of these were done by hand with a drill. It’s a technique that I kind of invented myself because I did it at the beginning of the sixties with this artisan. It’s a passionate work that has given me a lot of attention in the art world. So, with methacrylate I did a lot of things. Also lamps of course, because it lent itself as a material. The novelty was that it was a material that conducted the light. It was an interesting discovery, at least in terms of lighting, that later was used by others, also by Colombo, also with the same artisan [Joe Colombo designed table lamp Acrilica, that was produced by O-luce—Palainco].”

-

Left and right: Boutique Altre Cose in Milan in 1969, designed by Ugo La Pietra with Aldo Jacober and Paolo Rizzatto. The shop was composed of an empty room with large cylindrical methacrylate containers hanging from the ceiling, which contained clothes. The boutique was linked to underground disco Bang Bang by an inclined lift. Pictures by Saporetti, courtesy Archivio Ugo La Pietra.

Left and right: Boutique Altre Cose in Milan in 1969, designed by Ugo La Pietra with Aldo Jacober and Paolo Rizzatto. The shop was composed of an empty room with large cylindrical methacrylate containers hanging from the ceiling, which contained clothes. The boutique was linked to underground disco Bang Bang by an inclined lift. Pictures by Saporetti, courtesy Archivio Ugo La Pietra.

-

Did you work together in his workshop?

“Yes, in his workshop, which was small. He had an oven where we made these sheets, also the largest ones. [He laughs, as if talking about it brings to mind images of working in the workshop] I’ll tell you a funny story, it’s incredible. At a certain point all these sheets became large as these objects became large. [shows a picture of the shop Altre Cose in Milan] These here are very large sheets, but the oven was small, and they didn’t fit in. So, in order to be able to shape the sheet we had equipped a small room with a jet of hot air. Pfffffffffffft… [he makes a blowing sound as if to mimic the sound of the hot air jet.] He and I were taking the sheets, we held them in our hands with the front directed to the air and when the hot air finally softened it, we took the sheets and threw them on a male mold and we worked on it to make it take the form.” [He gestures with his hands as if working the material]

You wore gloves, I assume?

“Yes, because we practically had no female mold, to give the sheet its shape. We

really needed those gloves. We put the plate on the mold but still had to shape the hot plate by hand.”You really made them by hand, you worked with the material yourself and were not just watching?

“No, I actively participated in this handcrafted work, not like with many of my works, for example in ceramics. Some of those I made myself, but often I gave a drawing to the artisan. But these pieces, almost all of them I made myself.”

And in the same way you tried to make the small holes yourself?

“I made millions of holes…, but if you look at my paintings from that period it’s the same thing, there you also see small marks.”

Were you able to make Globo Tissurato entirely in the workshop?

“Yeah, sure, only the lower part he (Michele Moro – Palainco) couldn’t do. A company nearby did the metal part.”

It must be challenging that the globe of the Globo Tissurato needs to come out as a true globe.

“Eh, yes; the most difficult part of this cylinder is hollowing it out so that the two domes fit very precisely one inside the another, do you understand?” [He fetches a smaller Globo Tissurato that sits on a cupboard and shows it to us up close.] “Does this one close properly?” [It does.]

-

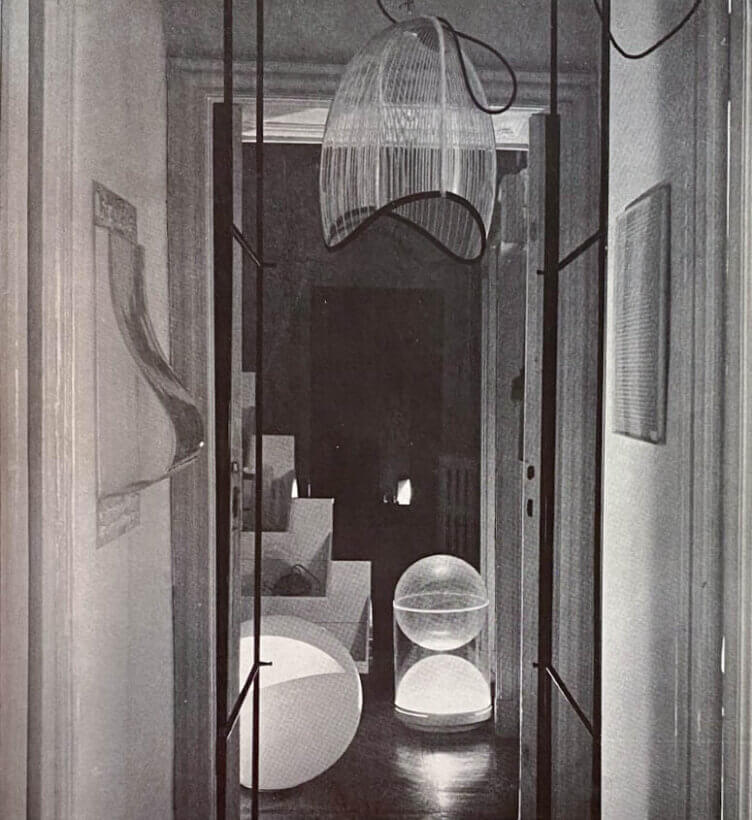

Objects designed by Ugo La Pietra in his home in Milan, as published in Domus in 1971 (from the Palainco archive).

Objects designed by Ugo La Pietra in his home in Milan, as published in Domus in 1971 (from the Palainco archive).

-

“My neighbour was a young engineer who worked at Siemens. When I was at the cinema, I was fascinated by the light that goes out slowly before the film starts. There they used very large equipment, but I turned to my neighbour to enquire about how we could make it smaller. This is how we invented the light intensity regulator. It was done for the first time for this lamp. It was a small object, also in methacrylate. Then he started a small company to produce these regulators. I supplied the first Globo Tissurato lamps to this artisan company. So, now when they are published, they often attribute it to Zama Elettronica, because it was the company that produced only a few pieces. Not more, because they didn’t sell. But this company mainly made the light intensity regulators. The novelty of this lamp was not only the fact that it was made of methacrylate and it had reflections, but above all because it had the first light intensity regulator [This would of course become famous as a dimmer—Palainco]. This is why we put these things into production, because they had the latest technological innovations.”

-

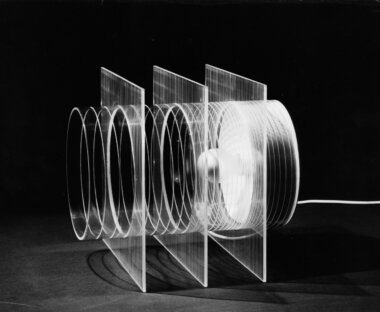

Another object that you made the was the table lamp in the form of a cylinder, which was a type of interactive lamp?

“Well, interactive, as in everyone could change the colour of the light.”

“I never understand how I did certain things. [He laughs, while looking at a picture of the lamp.] I don’t have it here, so I can’t say how I managed to find a system. Ah, yes… [laughs heartily], it’s the hardest thing… This is a circle; how did I get this circle in without cutting it in half? I don’t know, I don’t know how I did it. Technically I don’t understand. This is a circle, to put this circle here I need to cut all this here. I don’t remember anymore. No… There must be a trick, but I don’t remember it. Because when I look at it I think: How did I do it? If I had it here, I would remember how I did it.”

-

Globo Tissurato lamp in methacrylate, produced by Poggi in 1968. By experimenting with the methacrylate sheets Ugo La Pietra discovered that they could be inflated. As a result, the texture formed by the dead holes transformed. Courtesy Archivio Ugo La Pietra.

Globo Tissurato lamp in methacrylate, produced by Poggi in 1968. By experimenting with the methacrylate sheets Ugo La Pietra discovered that they could be inflated. As a result, the texture formed by the dead holes transformed. Courtesy Archivio Ugo La Pietra.

-

It seems that to be able to make all these models, experimenting is very important.

“Yes, I tell my students: ‘Today we’ll build a wall together.’ In the design world, that doesn’t happen. There is no knowledge of materials. Nobody knows this route, nobody ever spends all day in the workshop to work and look, which is the most important part. Because by looking at how the material moves one discovers its qualities. Do you see that thing there? A sheet comes out of a machine, but if you stop it with your hand… from there you can make an object. Like this you can also make inventions. In the workshop, by starting to drill the methacrylate sheets, I also discovered that these sheets could be inflated. And because of that, the texture transformed, because since the sphere is large here and thin here, the holes change completely. There is a modification of the texture in terms of progression, and all this because of a technological fact, that is an inflation. But the inflation is done by a torch which blows and blows, and the inflating is very much up to you. That is also a technique, like the drill. You can make a hole all the way through, but if you only do it halfway through, the mark comes out.

So, if you look closely at the Globo Tissurato you can see that not all holes are the same?

“In fact, they can’t be the same, because when the plate inflates the part here is much bigger, and this part is thin.”

-

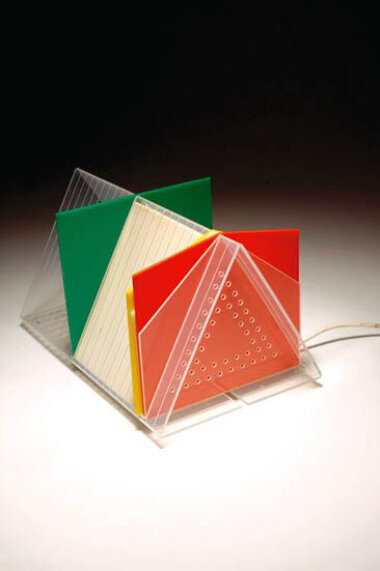

Left: Lamp produced by Zama Elettronica in 1967 and Poggi in 1968. Right: Triangular lamp with cross section, produced by Poggi in 1968. Both pictures courtesy Archivio Ugo La Pietra.

Left: Lamp produced by Zama Elettronica in 1967 and Poggi in 1968. Right: Triangular lamp with cross section, produced by Poggi in 1968. Both pictures courtesy Archivio Ugo La Pietra.

-

Before you told us I thought that the triangular lamp with cross section that was produced by Poggi would have been the first lamp that you made.

“No, let’s say it’s the cheapest lamp, as technically it’s simpler. The Globo Tissurato models need to be inflated and you need to have equipment, whereas this one (the triangular lamp -Palainco) is a plate with a resistant line, a steel wire where the electric wire passes. You put the wire in place, and it bends. It’s very easy, since it’s the only lamp that doesn’t need equipment, these play with much cheaper technology.”

Your lighting pieces in methacrylate are all wonderful objects, don’t you think?

“Eh, yes, I know…” [He laughs]

Even incredible?

“But still, everything I’ve done is never valued by anyone, ever. Even when they give me historical attribution for the use of plastic in the sixties, they don’t quote me in their work. Abroad yes, but not in Italy, because in Italy we are very much against each other. We have little space, we are all enemies, we go to war over a piece of bread. It’s difficult in Italy, very much so. But it seems to be our real advantage over the other creatives in the world, because by suffering so much, and the lack of space and opportunity we are much better than the others, because suffering leads to greater creative density.”

-

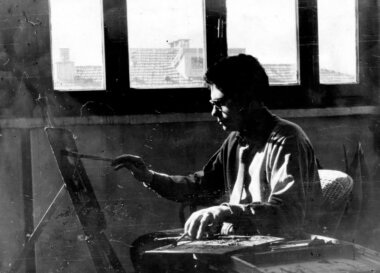

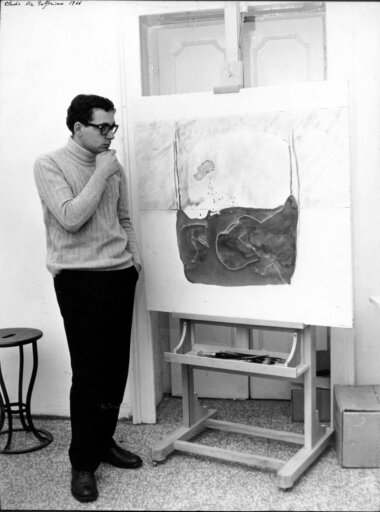

Left: Ugo La Pietra painting in 1959. Right: Ugo La Pietra with one of his works in 1966. Both pictures courtesy Archivio Ugo La Pietra.

Left: Ugo La Pietra painting in 1959. Right: Ugo La Pietra with one of his works in 1966. Both pictures courtesy Archivio Ugo La Pietra.

-

I would like to go back for a moment, if that’s OK with you. I’m curious about your background because many architects in Italy also had an architect father….

“An interesting question, because when I signed up at university in 1957, my classmates—we were few—they were all sons of architects or entrepreneurs, people who had a building company. My father’s only ambition was having a son with a degree. I was already painting in those years and therefore I wanted to go to the academy, but in Italy the academy was considered an inferior school. In the 1920s, we had the Gentile Reform, which said that higher education was divided into two levels: university, and the academy. The academy of fine arts and the academy of music are lower schools. My father, however, thought that a degree was something else, it wasn’t the academy diploma. He demanded I graduate. And so, not knowing what to do, I enrolled in architecture because it was the discipline that seemed to be closest to the world of art. But it turned out to be very far from it, in short. And so I had a lot of trouble finishing these five years of university, because at the same time I was exhibiting in galleries, I was an artist.”

So, during your studies you already understood that you didn’t want to live only in the world of architecture?

“Exactly, already as a student. There is a relationship between all of this. I continued to transfer experiences between architecture and the world of art and design. And I graduated with a thesis called ‘La Sinestesia between Arts.’”

Did this put you in a difficult position?

“It was a tragic choice: In the world of architects, I am the artist in the negative sense of the word, in the world of artists I am the architect in the negative sense, in the world of design, even there…I am nowhere. Living in a society that does not accept you is like ending up like Leonardo himself, who was a great man, but who was never accepted by society. Poverino, when he worked in Rome, they didn’t let him do anything. Because he was a good painter, yes, but he also dissected corpses to see how they were made inside—he did everything. And so, he wasn’t as highly regarded as Rafaello, the painter. Even when they say: in the Renaissance, these figures did a bit of everything. Yes, Rafaello also did architecture, but Leonardo who did a great many things, and ended up in France to die without any assignment. It is not easy.”

-

Ugo La Pietra on Il Commutatore at seven o'clock in the morning, 1970. Il Commutatore as part of La Pietra's long research entitled 'Abitare la città' offered an instrument for decoding the environment. It can assume different inclinations allowing each person their own point of view and individual reading of the external reality. Courtesy Archivio Ugo La Pietra.

Ugo La Pietra on Il Commutatore at seven o'clock in the morning, 1970. Il Commutatore as part of La Pietra's long research entitled 'Abitare la città' offered an instrument for decoding the environment. It can assume different inclinations allowing each person their own point of view and individual reading of the external reality. Courtesy Archivio Ugo La Pietra.

-

Yours is a very beautiful story, because it shows us the path that you have followed and the study you have made of man, that these objects are part of. They were born…

“Exactly, yes, they were born because I became a great observer, so perhaps one of the disciplines in which I am most expert is anthropology. It means that I look at things and people, the world. From there I deduct things. An anthropologist is one who has the ability to read the behaviours of individuals and somehow reveals their particularities, novelties, exceptionalities. So, I have my basic discipline, which isn’t painting or architecture—it’s anthropology, the ability to observe and deduct indications. And then a creative process mixes there. And yes, there is a very ancient reason that this capacity of observation arises above all. Just after the war my mother took us to the cinema every evening, for many years. Cinema, as a world of vision and storytelling, was the basis of my training. So, I have some visual training in storytelling and visual storytelling.”

Were those Italian films?

“No, above all foreign ones, because after the war all American films arrived. It is from there that I also became very passionate about jazz. In Italy there were only many singers, but by looking at American cinema, jazz music had also arrived, especially Dixieland and swing. And from there all the artists of my generation were first of all jazz musicians.”

Did you play yourself?

“Yes, the clarinet.”

“Since the mid-sixties, life has changed a lot in Italy, and for everyone. The first results of the so-called Italian Boom could be felt when one left school or university and found a job.”

Was it an exciting period for you?

“Well, yes, it was exciting because there were many opportunities. Every day there was a discovery, every day you could be doing things. But then, especially for me, the best years of my life were the seventies. When society had truly lost its power [laughs], and then one could do almost everything freely because the constraints were dissolved and therefore society did not impose its rules on you, because the rules had almost been lost.

The certainties had now disappeared and it was a period of great crisis, but the crisis was stimulating, because the crises in Italy were gli anni di piombo [the Years of Lead, a period of turmoil and violence in Italy—Palainco] the guerrillas, of urban affairs, of violence. But all of this was healthy, because it was a situation that allowed you not to follow the paths set by society, that told you what to do and what not to do. You were free; freedom was not simply won, but it was freedom due to a fact that society had lost its rules. Uprooted. And so no longer having the opportunity to tell you what to do, you were free. Do you see? Until they started shooting people, that was an escalation.” -

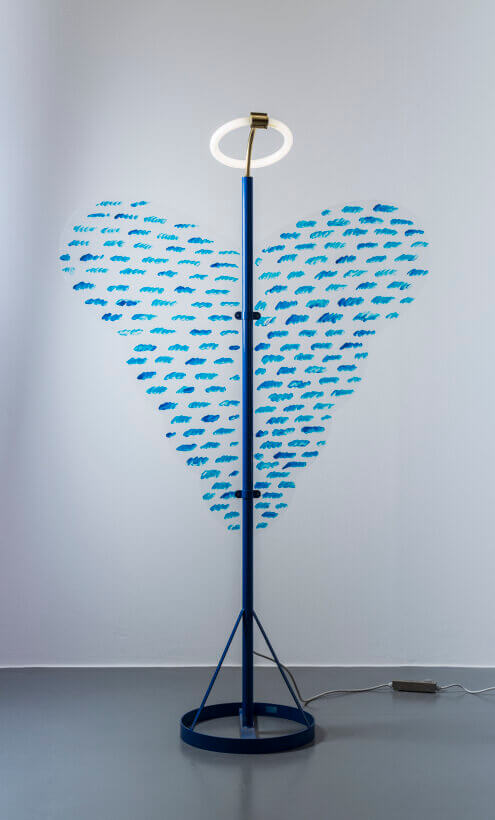

Floor lamp Arcangelo Metropolitano by Ugo La Pietra in lacquered steel, transparent plexiglass painted panels and fluorescent tube, was designed in 1977. Pictured here is a re-edition from 2007. Picture by Tiziano Doria, courtesy Galleria Bianconi.

Floor lamp Arcangelo Metropolitano by Ugo La Pietra in lacquered steel, transparent plexiglass painted panels and fluorescent tube, was designed in 1977. Pictured here is a re-edition from 2007. Picture by Tiziano Doria, courtesy Galleria Bianconi.

-

We sit at the far end of the studio at a large square table that is covered with books and objects. With his vivid eyes, agile movements and sonorous voice Ugo La Pietra doesn’t seem a man in his mid-eighties. In the 1970s, as part of an art project, the creator of 2800 objects designed the floor lamp Arcangelo Metropolitano.

“The Arcangeli are part of the longest research that I have done. They were exhibited at the Triennale in 1979; it was research for which I photographed practically all objects of street furniture that were around. I converted them into domestic objects to demonstrate the profound difference between violent street furniture, which was full of separations and violence, and domestic furniture, which was very comfortable and designed for our daily essence. So, these two worlds were both furnished, but in completely different ways. I put these two things together in a very provocative, almost ironic way. Among the created objects was also the Arcangelo, that had a dual function. Not only as a model for this story, but I also used it to place it in the Milan subway to express my disagreement with this space, that had been built as a second city. There was a city above and a city below, which was a strange thing, because the latter was all the same, while the city above was all different in every corner. So, inventing a second underground city is a good idea, to work on certain things, but with that characteristic of diversity, which belongs to us. But on the contrary, everything looks the same underground. So, I brought these lamps to tell that I certainly didn’t agree with that way of thinking. Instead, I was closer to the Stockholm Metro, which was thoughtfully designed in the 1950s to a scenographic extent that responded to the city above. Underground they built something that could be transferred to the world above. So, also the city told things, which gave the citizens space to live. Not just to move through quickly. That was the concept”.

-

Left and right: Arcangeli Metropolitani in metro station Melchiorre Gioia in Milan in 1977. For this project, that was part of a larger research, Ugo La Pietra created Arcangelo Metropolitano. A pole as part of street furniture was transformed into a spectacular lamp. Courtesy Archivio Ugo La Pietra.

Left and right: Arcangeli Metropolitani in metro station Melchiorre Gioia in Milan in 1977. For this project, that was part of a larger research, Ugo La Pietra created Arcangelo Metropolitano. A pole as part of street furniture was transformed into a spectacular lamp. Courtesy Archivio Ugo La Pietra.

-

Looking at the photos of the Arcangeli in the subway corridor I wondered what the reactions of the public were like.

[Disapprovingly:] “The public never gives a damn! The public passes by, sees things and says: A curious thing, isn’t it… The public always reacts over a very long time. It takes a very long time for the public to become aware of something in a city. First of all, whatever one puts in the city, the public will reject it. It does not belong in their living space; a new thing has nothing to do with it. They would like to destroy it. Sometimes it stays, and over time, slowly, it becomes something that belongs to the public. But not initially, initially anything an artist or an architect proposes in a street or in a square is immediately rejected. It has always been like that. Even in Bernini’s time when they put up the fountains, they said: ‘How disgusting’ and they didn’t want them.”

-

Ugo La Pietra (third from left) at the Polytechnic University of Milan with his fellow students, including Renzo Piano (second from left) in 1961. Courtesy Archivio Ugo La Pietra.

Ugo La Pietra (third from left) at the Polytechnic University of Milan with his fellow students, including Renzo Piano (second from left) in 1961. Courtesy Archivio Ugo La Pietra.

Since the early 1960s, you have been researching the relationship between man and his environment. Do you know when this interest was born, maybe already at an early age?

“It’s difficult to say… [He thinks for a moment.]

No, I think I started to become aware of some things very late. Because I’ve always been a slightly dyslexic child, which means that I didn’t understand anything that they explained to me. I was always last in class; my grades were very bad. And still today, if you explain something to me, I will not understand. I don’t understand anything. I must understand through my own personal journey. And when I went to university, for example, I had bad grades there too. Then one day I took a book, and I started copying all the books in notebooks with my drawings, a monstrous job. But I had photographed all the notebooks

-

in my head, so when I took the exam, the notebooks responded… I didn’t understand anything, but I answered everything perfectly. I graduated with 110 cum laude, I was the best student in my class. But I didn’t understand much. In fact, I never understood anything. I’ve always figured things out through my own personal journey. So, I played in an orchestra for fifty years, but I didn’t know music. I’ve always painted, but I didn’t go to the academy. I made a very late film, but I’ve never studied the medium. I directed eight magazines, not just one. Directed means as they were small magazines, that the director did a little bit of everything, so you had to have some experience. I had it because I invented things myself. And this meant that until I was twenty I was not conscious, I didn’t understand, I didn’t know anything. I had a world that was, let’s say, a bit fantastical, but I didn’t have a relationship with reality. And then I began to understand how to approach reality through my own personal journey. Because in first grade in my notebooks I wrote the letters backwards, the i with the dot underneath. I was just a dyslexic. And so, slowly, I went through all that and became someone, who in the last two, three years wrote eleven books. I also write a lot, but I’ve never done any school, maybe I didn’t even know how to write. In short, I learned it by myself. This is a bit my characteristic and therefore I at sixteen, seventeen—at fifteen, fourteen, ten I was a lost child, boy, young man. I didn’t know what women were, I never understood anything, it was terrible. A very difficult life. Then … I also became good at things, but it took a long time.” [laughs]

How wonderful!

“You wouldn’t expect it, but that’s how it was. Even today, if a friend says: ‘I’ll teach you how to play this card game’—even if it’s very simple, while he’s talking I hear nothing, absolutely nothing. To this day I can’t remember the simplest things, a joke for example. I have no memory if it’s not visual. But the simplest joke told in the most idiotic way, I say: ‘Tomorrow I’ll tell you’— but I don’t know it anymore! It doesn’t stay.”

Apparently, you are a very particular case, but this perhaps teaches us that each of us must follow their own path?

“Yes, it would be better, because then it will bring you greater results. If, on the other hand, you follow paths that were already traced by others, it’s difficult to excel, to invent, to do things… yes.”

Maybe you’ve been fortunate in this respect…

“Yes, because I don’t have role models to follow, but I do what I want every day and I follow my own path, which is very tortuous, so it’s definitely not… precisely because of my shortcomings, yes.”

-

- Palainco would like to thank: Ugo La Pietra, for sharing his beautiful stories.

- We would also like to thank: Simona Cesana for her kind support.

Unless otherwise stated, all material is sourced and/or generated internally. All rights reserved.

- Text: Palainco, Koos Logger & Ingrid Stadler.

- Image sources: L'Archivio Ugo La Pietra, Galleria Bianconi, the Palainco archive.

The article and its contents may not be copied or reproduced in any part or form without the prior written permission of the copyright holders.

Published on: 21 March 2023