“I used to tell myself that I have the magic touch”- Tobia Scarpa

“This is a profession that demands a collection of fantastic acts.”

We meet Tobia Scarpa, architect, restoration architect, designer, teacher, who has worked with many Italian companies like Benetton, Cassina and Flos on a Sunday morning in his home in the province of Treviso, not too far from his birthplace, Venice. He and his wife Valeria give us a warm welcome and within ten minutes after our arrival Tobia Scarpa invites us for lunch with their friends in a wonderful osteria, to take place after the interview. The following conversation is translated from Italian.

-

You have done more than forty lighting models.

“I don’t know… I know that I have done a lot. [laughs] I’m not an artist, I’m a producer of things that are sold.”

Most of the lighting models that you did, you made for Flos.

“I gave birth to Flos, together with i Castiglioni. Actually, to tell you the truth, as a young man I did the graphic parts of this new activity that was to come about. When the Castiglioni brothers [Achille and Pier Giacomo Castiglioni– Palainco] had met the managers, they talked to me like a father and mother talk to a child. They said: ‘We can’t work with that one, let’s forget it.’ And I saw the opportunity vanish before my eyes, because if it was up to the Castiglioni brothers –who were famous– I wouldn’t be the child who was working with the company. So, I said: ‘No, I’m committed!’ and they were in, and so Flos was born.

About the name Flos, Achille [Castiglioni– Palainco] called me and said: ‘Let’s call it Flora,’ and I said: ‘Wait, let me have a look. No, maybe Flos is better.’”

-

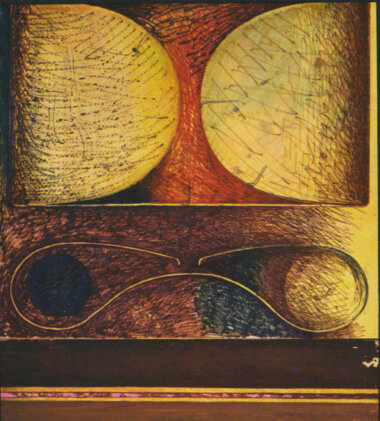

Bilobo pendant in frosted and metalised glass, and Sfera pendant in frosted glass, both models with support in anodised aluminium. Bilobo and Sfera were designed by Afra and Tobia Scarpa and produced by Flos. Picture shown is a detail of a page of an original Flos catalogue (Source: The Palainco archive).

Bilobo pendant in frosted and metalised glass, and Sfera pendant in frosted glass, both models with support in anodised aluminium. Bilobo and Sfera were designed by Afra and Tobia Scarpa and produced by Flos. Picture shown is a detail of a page of an original Flos catalogue (Source: The Palainco archive).

-

“There were a lot of small things put together. At the time, they were considering the possibility of a new product company. The gentleman who generated this stimulus was Dino Gavina. At the time he was a small industrialist who had also begun to build a shop to sell his products. He had the Castiglioni family and a hypothesis. That hypothesis was Carlo Scarpa. So, Dino Gavina asked Carlo Scarpa to draw objects for him. My father said: ‘No, I don’t draw objects.’ because he didn’t know how to approach the subject. He would have made a unique object for your home by studying everything, by making it even more beautiful, because that was where papà dominated. He hadn’t understood the fluidity of so many elements that involved the presence of an object on the market. And so, he started by saying no. I asked him: ‘Can I try?’ And he said: ‘If you want to do it, go ahead.’ He was someone who made drawings to plan things. In order to make things, he had to draw first.

And so I deformed myself; I make the thing first, and what I then draw becomes easier for me. For an industrial product this is perfect: you can’t have the ability to first draw for the final object. The final object will be understood by a quick drawing that then gets corrected a little bit at a time for the technologies that are applied. Because there is the machine that produces, the mould, or whatever is needed.”

-

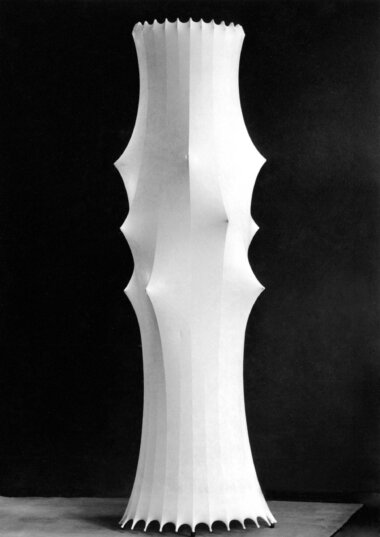

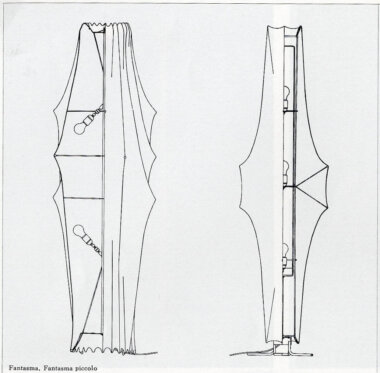

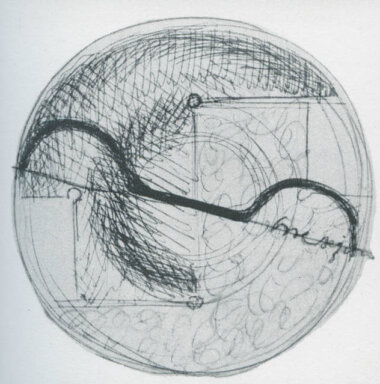

Fantasma, designed by Afra and Tobia Scarpa in 1961, was one of the first lamps made with the new material “cocoon” a resin that hadn’t been used before for the production of lamps. Fantasma and Fantasma piccolo (see drawing above) emitted a diffused light. They were both produced by Flos. Afra and Tobia Scarpa also designed the Nuvola pendant with the same technique. Achille and Pier Giacomo Castiglioni at the time also designed several models using the material (Picture Fantasma by Luciano Svegliado, source: Tobia Scarpa. Drawing Fantasma and Fantasma piccolo, source: Tobia Scarpa).

Fantasma, designed by Afra and Tobia Scarpa in 1961, was one of the first lamps made with the new material “cocoon” a resin that hadn’t been used before for the production of lamps. Fantasma and Fantasma piccolo (see drawing above) emitted a diffused light. They were both produced by Flos. Afra and Tobia Scarpa also designed the Nuvola pendant with the same technique. Achille and Pier Giacomo Castiglioni at the time also designed several models using the material (Picture Fantasma by Luciano Svegliado, source: Tobia Scarpa. Drawing Fantasma and Fantasma piccolo, source: Tobia Scarpa).

-

Among the first lighting objects that Flos produced was a series of sculptural models, among which Viscontea, and Taraxacum by Achille and Pier Giacomo Castiglioni and Fantasma and Nuvola by Tobia Scarpa. For these models a foam was sprayed on a slender metal structure over which a nylon yarn was applied. The foam later turned into a solid film. This application of a material, which was originally developed to protect US army vehicles while being transported, was a true innovation.

When you started to work for Flos, what did you think of the new material they got hold of, “cocoon?” Did you like the idea of working with it?

“Sure, in fact I immediately started to draw some things. I don’t remember. I did Fantasma, I think. But it’s been a long time…”

Yes, I know… [We laugh].

“No, because I have the habit that when I’ve done something I want to forget it; because if I don’t forget it, I can’t have another thing to work on, the novelty let’s say. Because if I drag it along… it will be the complete opposite of what my father did. He would have something which he could repeat 25,000 or 30,000 times, but they would be different things, while I perhaps was already deformed. If you work for technical, mechanical production things can’t be repeated indefinitely with the machines that work with that logic and that have that presence, and therefore it’s a culture that evolves. The important thing is to be aware of it.”

The new material, a resin, that was imported from the United States had never been used to make lamps, which was a real innovation.

“Yes, absolutely. When it arrived in our area the idea that you could make lamps with it was in a way infectious. In particular the company that produced these new product images was revolutionary, it later became Flos.”

It seems a great opportunity for a designer, your start with Flos.

“Yes, for me it was the ability to grow a great company. I thought: ‘What am I going to do, we have the potential, let’s use it and see what happens. I am sure, personally, that this thing we do is a winner’. I’m talking about thirty, forty years ago. Maybe even more, I don’t know.”

More, more than fifty…

“Why am I getting so old! Excuse me…” [laughs]

So, it was a big break?

“For me it was a unique opportunity. I thought: If I do everything right, I’ll be the first in my class.”

-

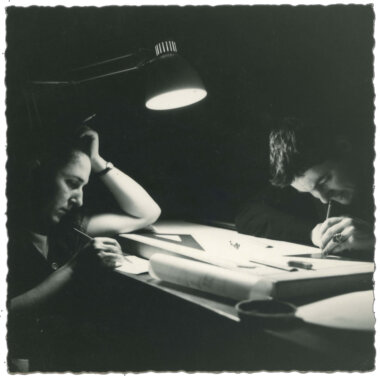

Afra and Tobia Scarpa working (source: Tobia Scarpa).

Afra and Tobia Scarpa working (source: Tobia Scarpa).

How did the collaboration with Afra Bianchin, then your wife, come about?

[Shrugging] “I don’t know, by instinct, and when you’re wrong you carry the burden. I have always worked with her. I think we were not yet married, but anyway. At university let’s say. To tell you the truth, I pushed my wife to go into architecture, though.”

You have made so many models together. What would you say was her strength?

“She was very critical and so I was just buying a huge amount of time, because if you are discussing and say: ’I would make this curve like this, or I would make this curve like that – it doesn’t make sense.

-

“I will make a curve like this” is already better.’ Then the presence that physically creates the design does not appear, but it was the most important element for making the design a vital, perfect, or an almost perfect thing.”

If you collaborate the idea is transformed?

“Of course, the misfortune of one of the collaborators is that there was no material part of her presence.“

You already started working together at university, doing good things, and were probably way ahead of other students?

“Even professors.“

Does it mean that you were successful from the start?

“I was trying to do things right. Right means that there is a gentleman who wants to make an industry, and who has certain potentials. There is a market that could accept these things, and there is a designer, an idiot, who can take advantage of this situation.”

-

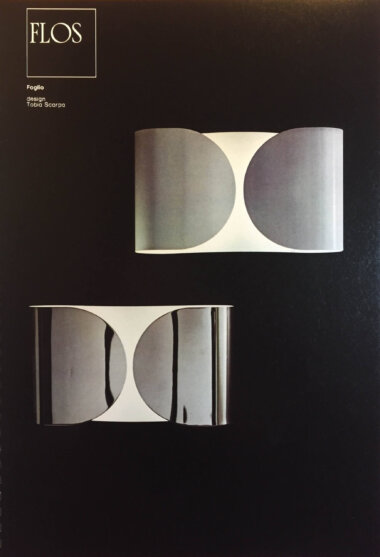

Drawing of Foglio wall lamp, the epitome of simplicity (above), designed by Afra and Tobia Scarpa in 1966 for Flos. The model in nickel-plated or enamelled metal gives a screened light (left) (sources pictures: Drawing Foglio: Tobia Scarpa, Picture original catalogue Flos: from the Palainco archive.).

Drawing of Foglio wall lamp, the epitome of simplicity (above), designed by Afra and Tobia Scarpa in 1966 for Flos. The model in nickel-plated or enamelled metal gives a screened light (left) (sources pictures: Drawing Foglio: Tobia Scarpa, Picture original catalogue Flos: from the Palainco archive.).

-

Another model that you made for Flos is Foglio.

“Yes, a single piece of bent sheet metal, but that one came about in a different way. The people who founded Flos, Gavina and others, weren’t salesmen. They were succeeded by relatives, and this became the Flos company. They wanted a novelty every day. They thought about selling, but the art of selling is like the art of drawing. They weren’t able to sell, and it’s a shame, but this is what happened. When I was designing something, they didn’t understand why I did this stuff. It could have been an intellectual game… It was a low level in short.”

But later they probably understood it?

“Yes, yes, afterwards… yes.” [We laugh.]

Foglio is simple, but according to you it’s a right thing?

“It’s semplicissima, but intellectually it’s a good design thought. However, its birth was a proud act because I didn’t have time to design it. Because to be able to design you need to be in a certain state, you need also to be capable of anger if necessary. Because if you say: ‘This will do, ‘it doesn’t have the right energy.”

“One of the owners of Flos, Marco Pezzolo, visited me at home. I lived with my wife in a building that I had built. He arrives in the morning, and I give him the big tour and we talk and talk. And in the evening we eat, and he doesn’t have the courage to ask me to design a lamp. And so, the moment arrives when he needs to leave, and he finally finds the courage to say: ‘I need a lamp.’ And as I needed to make something, I took a piece of paper and folded it and said: ‘Here you are!’”

A stroke of genius?

“Yes.”

It sounds so simple, but if it really were so simple everyone could do it.

“Everyone could do it, but an idea is something that doesn’t exist yet. How do you take an idea that doesn’t exist? An idea needs materialisation; in fact, designers are here exactly to carry out this kind of ideas.”

Maybe the pressure helped you?

“Certainly– the intellectual stimulus comes from pressure, from squeezing and stretching, from falling in love; anything and everything that is dynamic is good for thought.”

-

Fior di Loto (1961, left) and Nictea (1961, right) pendant lamps, both designed by Afra and Tobia Scarpa for Flos.

They give a filtered and concentrated light, and are made of polished or nickel-plated brass, or enamelled metal (Picture Fior di Loto by Luciano Svegliado, source: Tobia Scarpa. Picture Nictea: by Palainco).

Fior di Loto (1961, left) and Nictea (1961, right) pendant lamps, both designed by Afra and Tobia Scarpa for Flos.

They give a filtered and concentrated light, and are made of polished or nickel-plated brass, or enamelled metal (Picture Fior di Loto by Luciano Svegliado, source: Tobia Scarpa. Picture Nictea: by Palainco).

-

The pendant lamps Fior di Loto and Nictea are very particular.

“They are the first things I designed. They weren’t lamps, they were objects, and they didn’t give light, or just a little, while they wanted a lamp that really gave a lot [he pronounces the word with a lot of emphasis] of light. And so it all went south, in short.”

You on the other hand wanted to make objects to enjoy looking at, that were not just any lamp.

“Exactly. It was the concept of making a powerful brass metal object that can be polished as if it was silver or gold, that stands out in a room creating a structure.”

Fior di Loto and Nictea are timeless models, don’t you agree?

“I hope so; personally, I didn’t want to be a simple chain of events leading to the sale of an object.”

I understand, but this doesn’t mean that one is also capable of creating these objects that are still fresh.

“When we look at ancient objects, we see that they are bellissimi. Their only defect is not having someone who can produce them and sell them. But they could be sold. We are lucky enough that there is a company that has invented machines that make it easy to produce something that otherwise would dissolve in thought and there would be nothing left, or that would remain only in a written appointment or in a sign. Actually, those are not the things that remain, or that should remain. I don’t have the imagination connected to the rationalisation, to the formal identification that we then must have a glass of wine, and everything is resolved. While if you carry it out, it remains matter. And so the industry has produced things; the ability to produce has made it possible to materialise things that would otherwise vanish.”

-

Tobia Scarpa (source: Tobia Scarpa).

Tobia Scarpa (source: Tobia Scarpa).

-

We sit on Libertà chairs in a room in the former farmer’s house that Tobia Scarpa restructured himself. It is filled with his designs, with the lamps Papillona, Perpetua, and a prototype of a floor lamp. Talking about his work in a calm voice with a Venetian accent he regularly brings up his father, Carlo Scarpa, the genius architect and also a gifted teacher.

“He had a magical ability; he talked about a sign, a small object, a drawing of some artist, or a corner of a house that was suddenly illuminated by the sun. He talked about all these phenomena, these things that for him were the structure of his work. I don’t have this quality, but I understand it, I recognise it.”

Your father showed all these things to you as well?

“Oh yeah…, yeah, absolutely. I was the one who went to steal things from him. It always happened, already when I was very little.”

You probably already understood many things at a young age?

“Yes, we have very clear ideas and my experience has led me to help others. I could have done a lot more if the others had been a little bit more culturally active, but instead I found only bifolchi. Do you know what a bifolco is? Those who raise cows, intellectuals who know nothing. I have worked with industrialists to whom I tried to explain, but they just didn’t understand. They all liked hearing me explain, even my father, who was better than me, managed to flatter people in a way that they then claimed to always have known it. It’s a job like any other.”

“I don’t know how to explain it because it can be equivocal, but at the beginning of my career I made objects for sale, and I continued to do this for the rest of my life. To give myself a purpose that can be controlled. The artist has his own specificity, but he doesn’t know what will happen next. He could be lucky and become great, he could be intelligent, he could be abusing this quality, or stay in his harmony. However, the potential is there. And what happened to me: I was able to build the continuity out of potential. So, I know how to design. I will help this design to be appreciated by all, that’s what I can do with ease. I don’t know now as I’ve gotten old; maybe I don’t care anymore, but when I was young it was a wonderful tool because I was able to flatter others. Flattery… Therefore, consequently I was able to do what I wanted, which was to draw an object knowing that the object was the right object in the environment of production. No longer in the sphere of the artist, who makes a unique object. A unique object means with an absolute value and an equally great difficulty to convince others that the object is not unique by mistake. Instead by lowering everything to the level of continuity you can work through the industrial product. You have lost, let’s say, the magic moment of the unique sign. It’s a kind of trivialisation of something that is impossible to explain to others. In the moment when it’s trivialised, even if you don’t understand it, you can approach it. This is the game that I was able to play.”

How beautiful! When did you understand that you had this ability?

“Forever. It’s not like you can develop these things; either you have them, or you don’t. When you have them, you already had them when you were born.”

It seems a great force.

“Yes, it’s a great ability, but if you use it badly, you destroy it.”

Do you call it a talent, a gift?

“It’s not a gift in the absolute sense. It is a gift in a relative sense. It is a potential gift that you can develop. On the other hand, on my mother’s side they were artists, on my father’s side there was his quality. And the child? Am I going to be a blacksmith, I’m going to do physical work, or will I throw myself into madness? Because this is a profession that demands a collection of fantastic acts.”

-

Tobia Scarpa and Afra Bianchin in the 1980s working on a floor lamp featuring two curved screens. Picture by Cesare Colombo (source: Tobia Scarpa).

Tobia Scarpa and Afra Bianchin in the 1980s working on a floor lamp featuring two curved screens. Picture by Cesare Colombo (source: Tobia Scarpa).

When did you realise that you could be a good designer?

“I can’t explain well, because at the time I met a person who was starting to make clothes [Luciano Benetton, with whom Tobia Scarpa and Afra Bianchin have worked for a long time– Palainco]. I have done more than the things he originally needed. He was a lucky man because everything went well. Maybe it was me who had the magic touch, how can I put it? I used to tell myself that I have the magic touch, because the things I did were going well. It absolutely wasn’t true, but the consequences of a correctly oriented act in a situation that was well analysed worked out, because it was the right thing. But you don’t have to be very good to analyse something like this. We were all young at the time.”

Did you have the insight to know when something was right?

-

“A right thing is a series of values that you put in order because they must be your tools. So either it’s right, or it’s not done. For example, it’s different from the workmanship, my dad’s work, which comes from antiquity. That is, to work even at night to make a drawing. Every time I tried to make a drawing when creating something I preferred to modify it. So, it was better to modify it immediately, and then someone or myself could do the drawing. Drawing is a waste product; it is not a birth product. It’s quite complicated, because it depends on an ability to analyse, a desire to perform, a knowledge of machines– It’s a lot. Therefore, if a drawing should encompass all that doubt I doubt there’s anyone capable of doing it today. So, what happens: anyone who makes a drawing then must correct it. Then today technicians come forward, I use the word technique in an unkind way here. If the designer doesn’t have these skills, the object is lame, something is missing. So when the first prototypes are made, the technician says: ‘Look, you need to make this correction, and in the end the product turns out well, that is, it has its function, which is that it can be sold. But from an individual point of view it is a progressive fall in capacity. A designer must know how to do everything, otherwise he is not a designer.”

I was wondering if an object makes you happy when you feel the final object is right?

“Yes, right means: similar to happiness. That’s why I don’t want to make mistakes, because if I make mistakes, I need to discard it and I missed the opportunity.”

And afterwards the object also gives happiness to the user?

“If I give happiness to an object, the object produces happiness. This goes for anyone’s object, it always does, and that’s beautiful.”

Yes, absolutely. And for this reason it’s very important that the object is right.

“It’s right when the man who creates it possesses happiness, and he then gives it to others. An object, let’s say an art object, an object of ability, of essentiality, of uniqueness. Otherwise objects become just things. It doesn’t necessarily mean that things don’t make happiness, but they lack that intellectual drive that makes them universal.”

-

-

Biagio table lamp (1968) was designed by Afra and Tobia Scarpa and later produced by Flos. The lamp in white Carrara marble gives a direct and diffused light. Initially from a milled marble disc two half-shells were cut and glued together with two other halfs, to form two lamps. Later, when production equipment had evolved it was possible to produce the lamp from just one marble disc (sources: picture Biagio: Tobia Scarpa. Drawing: Tobia Scarpa).

Biagio table lamp (1968) was designed by Afra and Tobia Scarpa and later produced by Flos. The lamp in white Carrara marble gives a direct and diffused light. Initially from a milled marble disc two half-shells were cut and glued together with two other halfs, to form two lamps. Later, when production equipment had evolved it was possible to produce the lamp from just one marble disc (sources: picture Biagio: Tobia Scarpa. Drawing: Tobia Scarpa).

-

Another model that you made for Flos is Biagio, that is made of marble, an unexpected material for a lamp.

“That’s another story, Flos has nothing to do with it. A friend of my father’s, Licisco Magagnato, who was in charge of the museum in Verona [Museo Civico di Verona– Palainco] goes to my father and says: ‘I want to make an art exhibition. My father says: ‘No, I don’t have time, go to Tobia.’ I get in the car with him and there’s nothing more beautiful than having nothing to do. And he takes me to another part of Italy, near Lucca. We have a good time, we look around and he says: ‘You should design something for me, why don’t you draw me a lamp?” and he takes me to this village where they work marble. Beautiful, a lamp. At the time there were no machines to make what I designed; a circle which is then cut in two, and the two pieces are assembled to make the lamp. The basic element is round, but to me round was too banal, so I cut it in half. Later the machines arrived that could make it in one piece, but they weren’t there at the time. The machines made a kind of hauberk, which is one piece of marble that comes clean cut like this. It is empty inside; there the bulb sits that gives the light. There was a stimulus because there was nothing in marble yet. It wasn’t my fault.”

There is no mention of guilt…

“Nevertheless, it should always be necessary to speak of guilt because guilt is part of life. That is, without guilt, there is no activity. A lamp is banal, a silly thing, but even that follows the thread of the logic of all the parts: man, stone and all these things put together produce something, sometimes of a high level, sometimes less. Then it’s just a lamp, a banality. However, the intelligence that’s inside belongs to me.”

What do you think now when you happen to see a model that you have made?

“What I like about a thing from the past –that I don’t know because I’ve forgotten it– is critical analysis. If it has some formal justifications of quality. The question I ask myself is: ‘Do you make me look bad?’ if not, I’m all happy, but in critical and precise judgement. A critical judgement is like a sword for the intellectual.“

Some models are taken into production again, like Fantasma.

“It’s tempting, but every object has its own story, so, no, that doesn’t seem like a good solution to me. We are alive, we are intelligent, we are full of desires to design a new one, we will find a solution. Because this justifies you before the eternal. We work with very modest things that fall apart over time, but we design for eternity.”

-

- Palainco would like to thank: Tobia Scarpa for his generosity in sharing his wonderful insights and Valeria Salvador for her gracious hospitality.

- We would also like to thank: Ilaria Cavallari for her kind support.

Unless otherwise stated, all material is sourced and/or generated internally. All rights reserved.

- Text: Palainco, Koos Logger & Ingrid Stadler

- Image sources: Tobia Scarpa, Luciano Svegliado and the Palainco archive.

The article and its contents may not be copied or reproduced in any part or form without the prior written permission of the copyright holders.

Published on: 11 May 2023