“I managed never to copy my own work”

An interview with Bruno Gecchelin

Bruno Gecchelin was born a designer; at a very young age he started out by making numerous drawings and models of cars. During his career Gecchelin made products for many different manufacturers, for which he received three Compassi d’Oro, the oldest and most prestigious design award in Italy. Among his designs are more than a hundred lighting models. Still active and as enthusiastic as when he started out, we meet Gecchelin on a hot summer’s day in his studio in Milan that he shares with his son and two daughters, all three of them architects. The following interview was translated from Italian.

-

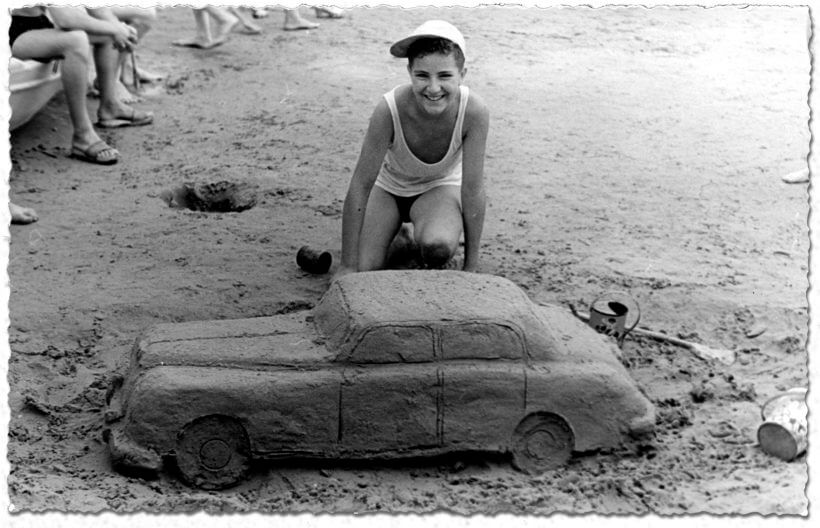

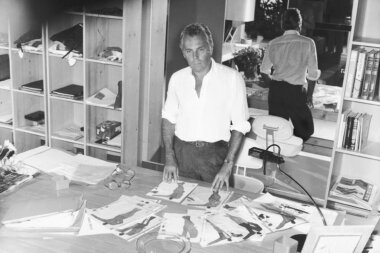

Main picture: Bruno Gecchelin in his studio (Source: Studio Gecchelin). Above: Bruno Gecchelin as a child at the beach with a sand sculpture of a car (picture by Umberto Gecchelin).

Main picture: Bruno Gecchelin in his studio (Source: Studio Gecchelin). Above: Bruno Gecchelin as a child at the beach with a sand sculpture of a car (picture by Umberto Gecchelin).

-

“Cars were my big passion when I was young. Apart from the fact that they were beautiful, they were useful. They were the perfect expressions of the technological avant-garde of those years. Here we were at the seaside, where I made these sand sculptures [he shows us the photograph with the sand sculpture of a car, see above]. I was the only one who did that, and everybody watched. I was very young when I did a lot of drawings, and made many models. The industrial product that was beautiful and well-made was my passion.”

-

The letter that Gecchelin received from General Motors in 1959 referring to the car designs that he had submitted (source: Studio Gecchelin).

The letter that Gecchelin received from General Motors in 1959 referring to the car designs that he had submitted (source: Studio Gecchelin).

The young Gecchelin was so serious about his car designs that he even sent a letter to General Motors to offer his designs to the company. He was very proud when he received a reply.

So can we say that you were already a designer when you were six years old?

“Subconsciously, I already was a designer. I loved the equilibrium and all the elements that from the point of view of a designer are important. In reality, I only did the aesthetic part of the design. It was not industrial design yet, as the technological part is a bit more complex. However, in essence I did the final part of the design. So you could say that I always made design.”

-

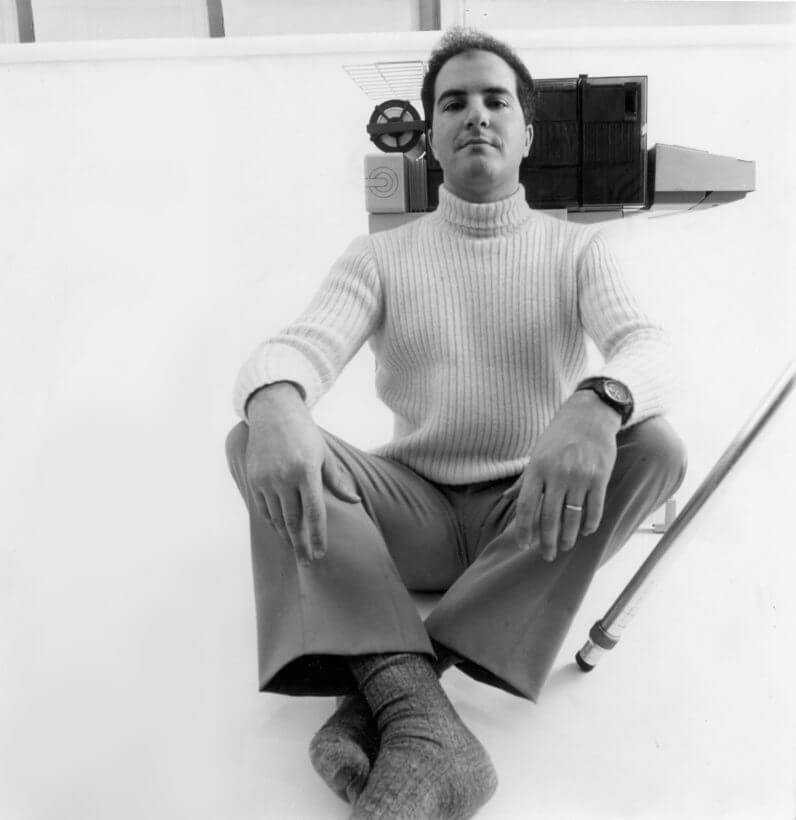

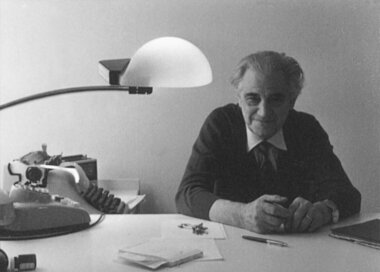

Bruno Gecchelin with Telescrivente TE 300 that he had worked on with Ettore Sottsass and Hans von Klier for Olivetti (picture by Bruno Gecchelin).

Bruno Gecchelin with Telescrivente TE 300 that he had worked on with Ettore Sottsass and Hans von Klier for Olivetti (picture by Bruno Gecchelin).

-

At the age of fourteen Gecchelin, whose father was a mechanical engineer, chose a technical school (ITIS Feltrinelli – Milano) to become a perito industriale, a specialization very close to engineering. At school he distinguished himself by his great aptitude for technical subjects. Before he received his diploma a fantastic opportunity came along: he was offered a job at Olivetti.

“At this school an Olivetti recruiter hired me immediately and sent me to the studio led by Ettore Sottsass in Milan [he shows us a picture of Ettore Sottsass, with collaborators, see below].

I was twenty years old. I had failed one subject at school, history or something, I don’t remember. I had to resit the exam in September, but they waited for me. Until I got the call from Olivetti I didn’t even know that this kind of work existed, I just wanted to design cars. The first day at Sottsass’ studio I showed him my car designs and he said: ‘Look, this is not design. This is styling, it’s only form. Design is the part that makes it possible to create these things.’ Design is design for the industry, it’s not for the craftsman, but for the industry.”

-

Team Studio Sottsass. First row center: Ettore Sottsass, second row right: Bruno Gecchelin (source: l’Espresso, June 1968).

Team Studio Sottsass. First row center: Ettore Sottsass, second row right: Bruno Gecchelin (source: l’Espresso, June 1968).

-

Years later Ettore Sottsass remembers meeting Bruno Gecchelin for the first time in the preface that he wrote to the book about Gecchelin’s lamps (see below, at the end of the interview).

Working at Sottsass’ studio seems an excellent start to your career?

“Sure, era bellissimo! Working with Sottsass, was different from working in a technical office or company workshop. First of all he was an artist. Maybe that’s why there were certain things he didn’t like to do, such as drawing objects in a precise way and getting into the technical and productive aspects of the Olivetti work program.

I helped him by making coloured sketches, photographs, technical drawings and by meeting engineers in Ivrea [at Olivetti’s head office] to discuss and improve the feasibility of the products that he conceived. I helped Sottsass, and in certain respects Sottsass helped me. He had a very artistic vision of the situation, which was philosophically very advanced.”

-

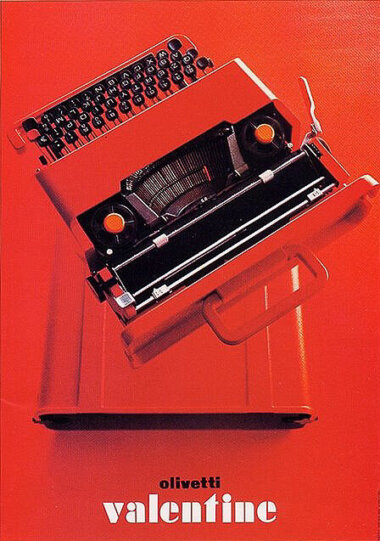

Iconic typewriter Valentine designed by Ettore Sottsass and Perry King for Olivetti (picture on the left, Olivetti publicity, 1969) and sketches for the Valentine typewriter by Bruno Gecchelin (picture on the right by Bruno Gecchelin).

Iconic typewriter Valentine designed by Ettore Sottsass and Perry King for Olivetti (picture on the left, Olivetti publicity, 1969) and sketches for the Valentine typewriter by Bruno Gecchelin (picture on the right by Bruno Gecchelin).

-

Did you become Sottsass’ right-hand man?

“In some respects, yes, with respect to what was done; the capacity, the possibility to be produced by an industry. I was directly involved in many of his projects such as the typewriter Valentine that, following his directions, I carried out from an aesthetic and productive point of view.

The fact that I was also a photographer gave me an extra eye. That is, as a photographer I saw something in a certain way, as a technician in a different way. It enriched me. I was very lucky to have that.”

-

The iconic portrait of Ettore Sottsass in the corridor at Studio Sottsass in Milan (picture by Bruno Gecchelin).

The iconic portrait of Ettore Sottsass in the corridor at Studio Sottsass in Milan (picture by Bruno Gecchelin).

-

During the years of collaboration with Olivetti, Gecchelin met Laura Maria Mandelli, who soon would become his wife and thanks to whom he decided to leave the economics studies undertaken at Bocconi to enrol together in the Faculty of Architecture. Also, Sottsass had recommended him to do so, to broaden his view. Once graduated in 1978, Gecchelin resigned from Sottsass design office, remaining an external consultant for two years and founding his own studio In Milan.

Wing was the first lamp that he designed for manufacturer O-luce—at the time one of Italy’s most prestigious and innovative manufacturers—led by founder Giuseppe Ostuni. The halogen lamp had just been invented. The new bulbs were small, though very powerful, and prompted new designs.

-

Table lamp Wing, that Bruno Gecchelin designed for O-luce (picture by Bruno Gecchelin).

Table lamp Wing, that Bruno Gecchelin designed for O-luce (picture by Bruno Gecchelin).

-

“I was still at Olivetti when I met signor Ostuni. He said: ‘I need a table lamp with a halogen bulb.’ So I thought about it. Since those lamps gave off tremendous heat one should not touch them, and furthermore they were small. The miniaturisation of the object in general fascinated me. So I needed to keep the design small. The idea was to do this [shows the head of the Wing lamp]. The parts are all identical. We needed just one mould for the little fencing, and a structural element. It didn’t cost signor Ostuni much, this mould, which had also been used by Joe Colombo. And it was made into one of the most beautiful lamps in the world.” [He shows us the picture of Giorgio Armani with the Wing table lamp on his desk, and laughs].

-

Giorgio Armani with the Wing table lamp on his desk (source: Vogue).

Giorgio Armani with the Wing table lamp on his desk (source: Vogue).

So Wing was an immediate success?

“Yes. Signor Ostuni had the great ability to captivate those who entered his shop at the foot of the Torre Velasca [a skyscraper in Milan, part of the first generation of Italian modern architecture]. It was a kind of cellar or warehouse, where they assembled lamps in the evening. When ladies arrived to snatch up the lamps of Joe Colombo he said: ‘Madam, take the lamp, take it home, and if you like it, you pay me. If you don’t like it, bring it back.’

-

Not one of them ever returned. So he was very successful in this respect: Tocca, assaggia e vedrai [literally: Touch, taste and you will see].

Ostuni was an industrial who took pleasure in the things he did. In the evening he went to his workshop and said: ‘I am going to say goodbye to my little girls,’ which were the lamps that were ready to be finished and to be put in boxes and be sold. He was a romantic.”

-

Giuseppe Ostuni, founder of O-luce with the Dogale desk lamp, designed by Bruno Gecchelin (picture by Bruno Gecchelin).

Giuseppe Ostuni, founder of O-luce with the Dogale desk lamp, designed by Bruno Gecchelin (picture by Bruno Gecchelin).

Mezzaluna floor lamp, designed by Bruno Gecchelin for Skipper (source: Studio Bruno Gecchelin).

Mezzaluna floor lamp, designed by Bruno Gecchelin for Skipper (source: Studio Bruno Gecchelin).

-

“After Wing everybody began to call me. Skipper called me to make the Mezzaluna, everybody called me. At Skipper, signor Pasini, who was very clever, had seen the things I had made and asked me to do something for him in a world that was completely different, because Skipper was open and was very generous and also they were able to invest a lot of money.

First of all, Skipper had a very beautiful shop in Via Manzoni, so it was in the centre of furniture shops and social life during the era of the economic boom. Meanwhile Ostuni worked downstairs in his workshop. Skipper on the other hand was better informed and knew better what to make. They had their own marble quarries in Tuscany. So I used marble right away for certain models. In short, there were many opportunities to make modern and luxurious things.

There was also the boom of the great power halogen linear 1000 Watt lighting bulb. And this stimulated me to make many new things. So I made a lot of beautiful things with Skipper and fortunately they were all successful.

Pasini was, most of all, a businessman. He didn’t have a factory, he had no workers. He had terzisti, contractors, small workshops and suppliers, who made things. And he organised everything.

Ostuni was a bit angry when I left him, but at Skipper I made things that were very different, which was always one of my qualities: to never copy things.” -

Ring table lamp designed by Bruno Gecchelin for Arteluce (source: Studio Bruno Gecchelin).

Ring table lamp designed by Bruno Gecchelin for Arteluce (source: Studio Bruno Gecchelin).

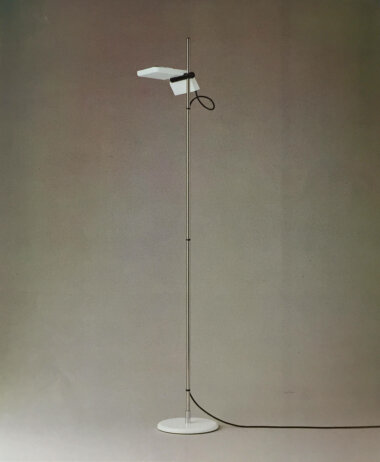

Model 1105 halogen floor lamp designed by Bruno Gecchelin for Arteluce as published in the Arteluce catalogue Lampade per Ufficio 1980 (from the Palainco Archive).

Model 1105 halogen floor lamp designed by Bruno Gecchelin for Arteluce as published in the Arteluce catalogue Lampade per Ufficio 1980 (from the Palainco Archive).

-

You also worked for Arteluce. What was their request?

“They wanted a halogen lamp that emitted a lot of light. They had an opportunity, because they had a foundry, where they produced metal castings [he shows us models no. 1105 and 271]. This is cast aluminium on a base. The parts were cast and were not made of sheet metal, since they had that factory. So in this case the company had a fusion press; other companies for example had the capacity to bend sheet metal.”

Desk lamp Ring is a distinct model, both for the shape and its flexibility.

“It is a very interesting lamp, because technically it is complex. You can turn it in any direction. It is a small masterpiece of practical technology, elegant and beautiful. It is very flexible, it gives you the opportunity to bring the light wherever you want. This was difficult to do, because the object was complex.”

How did you always come up with new ideas?

“I am very curious and very observant; I see details and from those details I get emotions that I take back and use. I don’t make too many sketches, I draw as it comes. If nothing comes, I throw them away. At a certain point, if I make a drawing that stands out, I stop: basta, finito. I don’t continue and make endless versions. I stop and take a chance on that one.

I make things for myself. I am lucky, because I like things that turn out well. But I am not excessive, exaggerated, so I know when I am on the right track. Afterwards I can personalise things according to the company’s demands. As long as I work to please myself it is all right.

I never wanted to see what others made, because I didn’t want to be influenced. I made drawings anyway, and if someone told me that it looked like something they had seen somewhere, it was fine. However, I did not want to see things beforehand.”

A commission by Japanese company Matsushita for a table lamp unfortunately did not lead to commercial success. The brief was given by Matsushita employees living in Milan, who apparently had forgotten that dimensions for the Japanese market needed to be smaller.

-

Desk lamp Pinocchio, designed by Bruno Gecchelin for Matsushita, a technically advanced lamp with a touch button, with which one could also operate the dimmer (picture by Bruno Gecchelin).

Desk lamp Pinocchio, designed by Bruno Gecchelin for Matsushita, a technically advanced lamp with a touch button, with which one could also operate the dimmer (picture by Bruno Gecchelin).

“At a certain moment people from the Japanese company Matsushita [now Panasonic] came over. They wanted a lamp based on an object that they had just invented, namely a very slim neon tube, which at the time was a novelty. So I made this lamp [shows Pinocchio lamp], that consisted of a transformer and an element. Since it was a desk lamp, I gave it these measurements. I called the model Pinocchio.

-

I even went to Japan and visited the home of one of their managers. However, the lesson here is that the lamps did not sell because they were too big for Japan. The general manager of Matsushita had a desk like this [indicates with his hands a very small size], where a work like this is useless. So we went to have a look at the shops where they were on offer, and in the windows they had put them on the floor, because they were too big for them. If only they would have told me, the asini [jackasses], that they needed a small lamp, we wouldn’t have had a problem. So we all missed a great opportunity there.”

-

-

Rigoletto floor lamps, designed by Bruno Gecchelin for Venini (source: Studio Bruno Gecchelin).

Paggio table lamp, designed by Bruno Gecchelin for Venini (above left, source: Studio Bruno Gecchelin) and sketches for Paggio table lamp for Venini by Bruno Gecchelin (above right, picture by Bruno Gecchelin).

Rigoletto floor lamps, designed by Bruno Gecchelin for Venini (source: Studio Bruno Gecchelin).

Paggio table lamp, designed by Bruno Gecchelin for Venini (above left, source: Studio Bruno Gecchelin) and sketches for Paggio table lamp for Venini by Bruno Gecchelin (above right, picture by Bruno Gecchelin).

-

When he received a request by Venini, Muranese glass makers par excellence, Gecchelin let himself be inspired by the colours of the Venetian laguna, carnival and the refined techniques of the glass makers.

“These are the sketches that I did for a lamp [he gets up and fetches the glass parts of Rigoletto, a floor lamp he designed for Venini]. When you put these parts together they form the base of a halogen lamp, in hand-made vetro battuto [a decoration technique of the glass used by expert glass makers in Murano].”

At Venini you were asked to create a desk lamp: Messer, which seems strange: how does one create a desk lamp out of glass?

-

Extraordinary desk lamp Messer, that Bruno Gecchelin designed for Venini. The structure is made of aluminium with an unusual element in glass (source: Studio Bruno Gecchelin).

Extraordinary desk lamp Messer, that Bruno Gecchelin designed for Venini. The structure is made of aluminium with an unusual element in glass (source: Studio Bruno Gecchelin).

“There were of course table lamps made of glass, but a desk lamp needs to do many things, you need to be able to move it and to turn it, because it is operational. To make all this out of glass is almost impossible. So I used glass to make the counterweight, it keeps the balance of the arm. The lamp itself was made of aluminium. It was a contrast within Venini, but exceptional, because they didn’t have it yet.”

-

The glass part seems to resemble a part of a piece of jewellery?

“That is because the glass was processed like that; the hammered part is something that they do with diamonds.”

Did you know about glass techniques before you worked with Venini?

“No, I didn’t know what glass-blowing entailed, but I actually went there to make it. It was fantastic!”

-

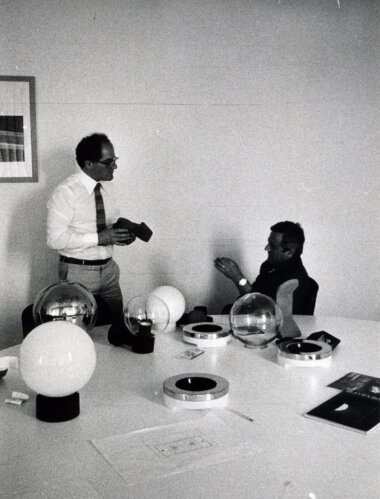

Bruno Gecchelin and Giannunzio Guzzini in the 1980s at iGuzzini during the development phases of a new product (source: iGuzzini).

Bruno Gecchelin and Giannunzio Guzzini in the 1980s at iGuzzini during the development phases of a new product (source: iGuzzini).

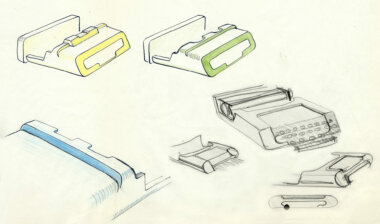

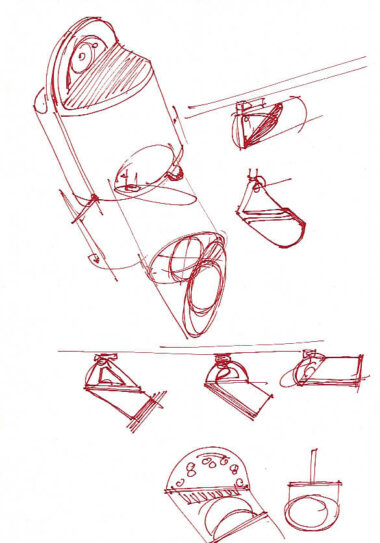

A sketch of the spotlight Shuttle by Bruno Gecchelin for iGuzzini (source: iGuzzini).

A sketch of the spotlight Shuttle by Bruno Gecchelin for iGuzzini (source: iGuzzini).

-

The Shuttle series by Bruno Gecchelin for iGuzzini (source: iGuzzini).

The Shuttle series by Bruno Gecchelin for iGuzzini (source: iGuzzini).

-

During his career Gecchelin received several design awards for the products he created, among which three Compassi d’Oro, Italy’s most prestigious design award. The series Shuttle, the spotlights that he created for iGuzzini, was one of them.

“For the Shuttle series the backside is the same for all models and then you can change the front part, just like lenses of photo cameras. There was this strangeness of this dimensional game.”

What did the Compasso d’Oro mean to you?

“It is a considerable qualification for those who do this work, so I was very pleased with it.”

For iGuzzini in collaboration with your wife, Laura Maria Mandelli, you also made Cirillo, which is a particular model, with that strange part in rubber. How did you get the idea?

“Guzzini had the possibility to make objects in plastic. A vase like this in plastic is already exceptional, so the exceptionality of the company Guzzini. We thought about how to finish it.

-

Cirillo table lamp, design by Laura Maria Mandelli for iGuzzini (picture by Palainco).

Cirillo table lamp, design by Laura Maria Mandelli for iGuzzini (picture by Palainco).

So we cut it off and, since it would have been stupid to have an external switch and in order to make it compact, we invented this strange part in rubber. It was a bit costly, because Guzzini needed to have a mould made and a switch.”

You made this model in collaboration with your wife?

“Yes, I always worked with her, I would show her things and she would say: ‘Hmm…, hmm…’ whenever I would show her something.

-

She was always very severe with me. She has great taste and sometimes she would say: ‘Stop here, this is beautiful.’ In this case I helped her, because technologically it would not have worked out.”

Did you always work upon request, or did you also develop independent ideas?

“I started from the demands trying to resolve the request also by looking at what the company was able to do. This was important, because if for example they only worked with marble, I couldn’t make something out of chocolate. So I went to see their opportunities and would ask things like: ‘What if we did a dimmer like this?’ And they would answer: ‘Yes, we could do that, because we have a special company that makes them.’ So I worked based on these experiences.”

-

Malia table lamp, that Bruno Gecchelin designed for Tronconi (picture by Palainco).

Malia table lamp, that Bruno Gecchelin designed for Tronconi (picture by Palainco).

-

“Opportunity and creativity, what does it mean? It means putting together the technological problems and form grace around it. I will show you [he takes desk lamp Malia from a shelf]. This lamp was produced by Tronconi. As you can see there is no wire. That is because the wire passes through here. The current, 12V enters over here, it splits, and goes to the lamp [he shows us the drawing of the model]. This is not just a drawing to make it beautiful. The difficulty led to the exceptionality of the object.”

It is difficult to characterise your style, do you think it is because the companies you worked for were all so different?

“I had the capacity to never to copy my own work. Every company had their own characteristics. In fact, I always tried to work like that. Besides, it was helpful that the lighting techniques always changed, there was always a new type of light.

-

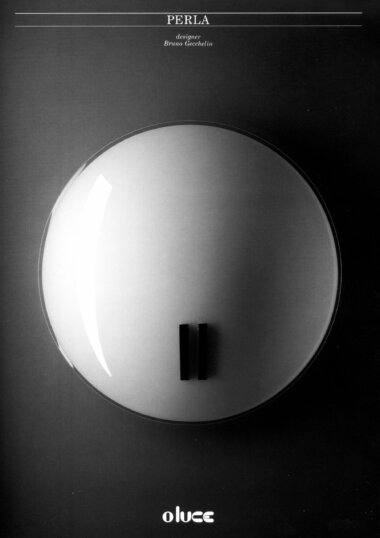

Perla wall lamp, designed by Bruno Gecchelin for O-luce (picture by O-luce, source: collection Bruno Gecchelin).

Perla wall lamp, designed by Bruno Gecchelin for O-luce (picture by O-luce, source: collection Bruno Gecchelin).

Mezzaluna is fantastic, and the first lamp I did, Wing, and Dogale and the disc with only these two signs [shows a picture of Perla].

There is this word, gratificazione. The object that you buy should gratify you, as well as be useful, give pleasure, etc. and of course not be too expensive. But most of all it should gratify you.”

Is this also important for you while designing?

“Yes. If it gratifies me, I am sure that it can gratify—among other things—the person who buys it.

It is my job to help people; this is extremely important. I am not there to exploit them. There is an element in helping that gratifies me, that gives me satisfaction, you see.

-

I have tried to transfer the great human and technical experience that I have accumulated over the years to my many collaborators and more recently to my son Lorenzo and daughters Sara and Arianna, who in various ways are all carrying on the founding values of Studio Gecchelin, even if in a different period of history.

Today the world of design has changed a lot and we need a serious and conscious reflection on the role of the designer. In the future I hope that our work as “shape and emotions creators” will continue to add functional beauty to our daily lives.”

-

Ettore Sottsass about Bruno Gecchelin

In the preface to the book ‘Pensate, Prodotte, Illuminate’ or ‘Conceived, Produced, Lighted’ by Bruno Gecchelin about the first fifty lamps that Gecchelin designed (Edizioni Lybra, 1990) Ettore Sottsass remembered the first day that Gecchelin arrived at Olivetti as follows:

“When I was a manager at Olivetti, a young man, not much more than a smiling young boy, came into the design studio. There were no secretary’s desks barring the way, and so he came straight to my desk with some large sheets of matt black paper on which he had done some coloured pencil drawings of an aerodynamic and sometimes chic car. I told him that the studio bodywork he had come to did not design cars, or do any styling work for that matter, but dealt in the design of static electronic machines. He carried on smiling and said that it did not matter, he wanted to become a designer and electronic machines were fine. He was utterly sure of himself and absolutely optimistic about the future. Perhaps those were times in which we all felt sure of ourselves and had faith in the future. In any case the young man, who was called Bruno Gecchelin, came to work in the design studio for many years, but I do not remember how many, meanwhile graduating in architecture, learning to be a designer, to design unusual cars, to take photographs, to work in a dark room, helping me a number of times and at a certain point designing lamps and light-shades in his spare time with such concentration, technical expertise, technological knowledge, inventiveness and intensity that he became successful in a very short space of time. Bruno Gecchelin therefore finally broke away from his old workshop and set out to brave the world of freelance architecture. It seems to me that he navigates this rough sea with great dexterity, as in the space of just a few years he has managed to put together a book like this which documents such a vast quantity of works – begun and completed – so many products, ideas, and solutions, and gives a continuous insistent vision of lighting in modern environments, workplaces and homes in which we pass our time. I think that Bruno Gecchelin really knows how to navigate the rough sea of this profession, and it is my opinion that he will reach great heights.”

– Ettore Sottsass

If you would like to be the first to read articles on designers and special designs, please subscribe to our newsletter.

-

- Palainco wishes to thank: Bruno Gecchelin, for his enthusiastic cooperation.

- Special thanks to: Lorenzo Gecchelin, for his kind and generous support.

- Source preface Ettore Sottsass: Pensate, Prodotte, Illuminate: 50 Lampade Di Bruno Gecchelin – Publisher: Edizioni Lybra - 1990.

Unless otherwise stated, all material is sourced and/or generated internally. All rights reserved.

- Text: Palainco, Koos Logger & Ingrid Stadler.

- Image sources: Bruno Gecchelin, Umberto Gecchelin, Lorenzo Gecchelin, l’Espresso, Olivetti, Arteluce, iGuzzini, Studio Gecchelin & the Palainco archive.

The article and its contents may not be copied or reproduced in any part or form without the prior written permission of the copyright holders.

Published on: 16 December 2021