“It was a model for life that was shared by all of us”

- An interview with Paolo Lomazzi

We meet Paolo Lomazzi at the end of the afternoon, in his Milanese top floor apartment, where some of his original designs are scattered around, like the Octopus coat rack in the hallway, the giant baseball glove Joe in the living room, and the table lamp Cloche in the kitchen. For most of his long career Lomazzi was part of the trio De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi, the studio that received many awards for their fresh and innovative designs. In 2018, Paolo Lomazzi received Italy’s most important design award, the Compasso D’Oro, for his successful career. Before we know it Lomazzi himself starts the interview, that was translated from Italian, with the following question:

-

“Who was the best lamp designer in the world, do you know? [After we fail to answer right away:] I know who: Ingo Maurer, a poet. Ingo Maurer, who was very good, made the lamps himself. He didn’t let others do it, otherwise such poetic things would never have arisen, such as the feather of the bird, the attached notes, very beautiful. I was moved.”

To prepare themselves for the interview, Lomazzi together with Donato D’Urbino made a list of the lamps that they created during their careers.

“We made a total of thirty-eight lamps; it’s absurd! We have made this list for you. D’Urbino and I had forgotten how many lamps we had made. And maybe this is not even all of them.”

-

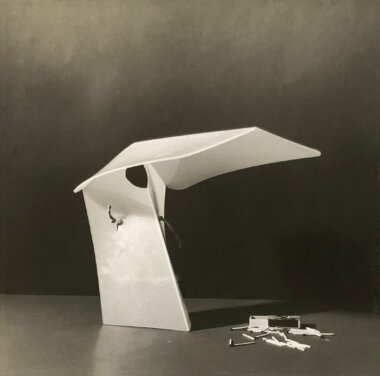

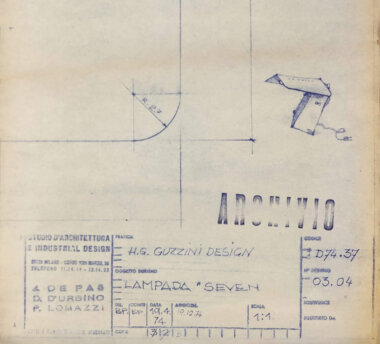

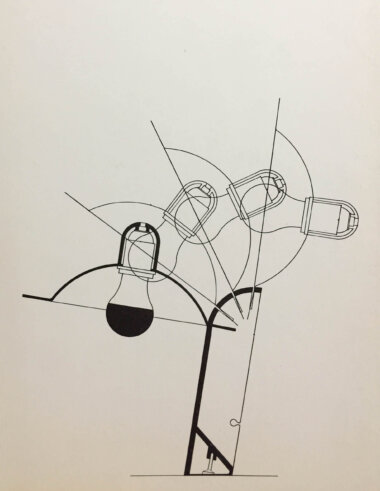

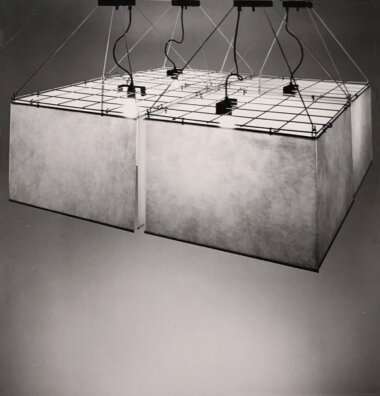

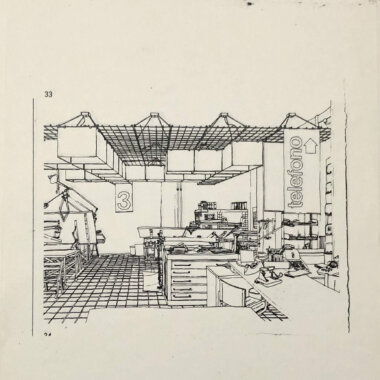

Left: A prototype of the Seven table lamp, designed by De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi for H.G. Guzzini Design. Unfortunately the model was never taken into production (source: L’archivio De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi, CASVA). Right: A drawing of the Seven table lamp for H.G. Guzzini Design (source: L’archivio De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi, CASVA). Main picture above: Paolo Lomazzi (picture from the private collection of the designer).

Left: A prototype of the Seven table lamp, designed by De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi for H.G. Guzzini Design. Unfortunately the model was never taken into production (source: L’archivio De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi, CASVA). Right: A drawing of the Seven table lamp for H.G. Guzzini Design (source: L’archivio De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi, CASVA). Main picture above: Paolo Lomazzi (picture from the private collection of the designer).

-

There are several models that have remained in your archive, that were never produced. Like this one, Seven, that you made for Guzzini. Do you know why it wasn’t taken into production?

“Maybe we’ve always made things that were a bit ahead of their time when we made them. It was simply made from a folded sheet, like Japanese origami. In those days things were a bit more elaborately embellished. But this here… [about model Seven—Palainco] how shall I say it… We had our own ideas about how to live, especially in the 60s and 70s, with all our research on inflatable structures. We were, let’s say, a bit avant-gardist.”

Things might have been a little strange to a lot of people at the time?

“Let’s say: very, very strange…, very, very strange!” [laughs]

Talking about illumination, which model that you made immediately comes to mind?

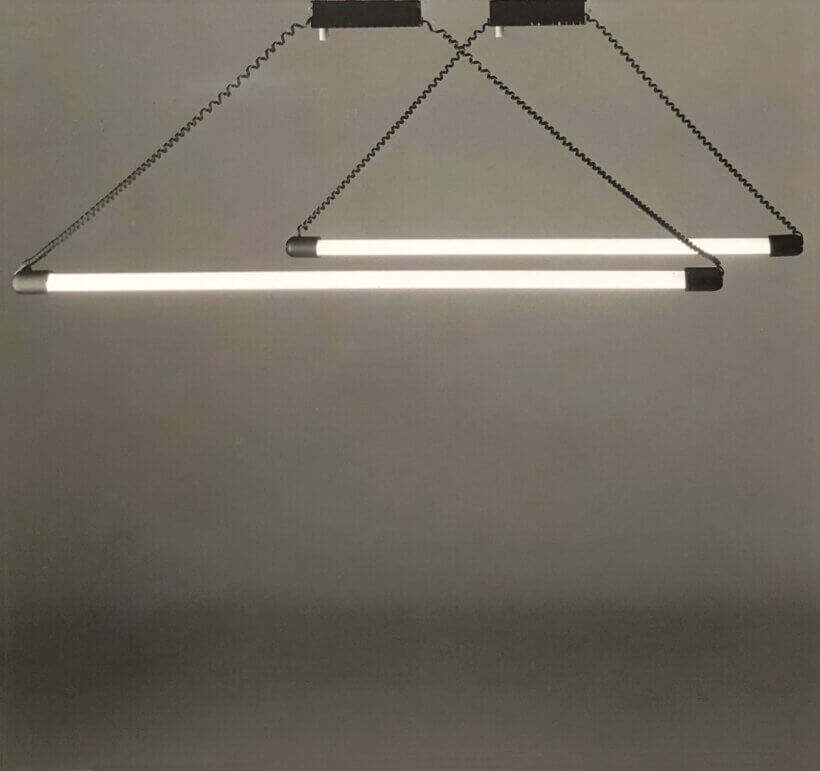

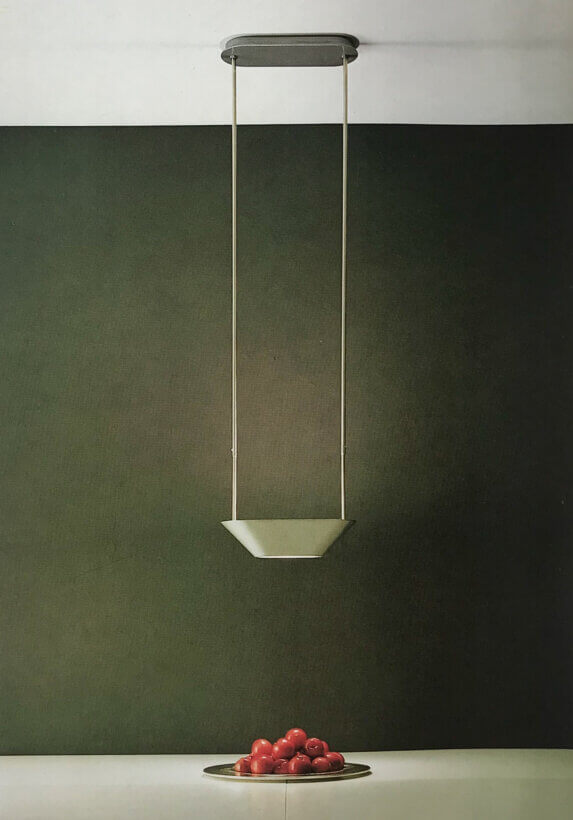

“ [Picks up a picture of Lampenudo, produced by Candle]. To make you understand, it’s not about whether I like it or not. Do you understand how it works? Where is the intelligence? One can’t see it, right? [He picks up paper and pencil and starts drawing the lamp.] This tube, this fluorescent lamp had a silver top. Here is shadow, the light is going in this direction. The head is made of rubber, and in whatever way you turn it, it gives light, like that, upside down, upwards. The end that was made of rubber had cut-outs inside, and you could twist it and direct the light.”

I didn’t know that, because it looks like a static object.

“Sure! [Laughs] But the intelligence was there.”

“This one [the wall lamp Dea, produced by Zeus] is also very intelligent, but where’s the intelligence? It’s easy, I’ll help you. Normally with wall lamps you either make the cord in the right position, or else the cord hangs down. This one, however, goes directly to the socket that is already there. You can make these high and long, especially at the bedside where there are always sockets. It’s these little things that please us.”

-

Lampenudo pendant, designed by De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi for Candle. Original picture by Aldo Ballo (source: L’archivio De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi, CASVA).

Lampenudo pendant, designed by De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi for Candle. Original picture by Aldo Ballo (source: L’archivio De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi, CASVA).

-

Can we go back to your youth for a moment, your grandfather had an art foundry that made art sculptures and decorations in bronze. Was that an interesting environment for you?

“We made nineteenth century things, Liberty [in English: Art Nouveau – Palainco], very decorated objects, but I learned the craft, as they say, from when I was a very young boy. I annoyed all the workers, I went to see how they made things, in other words it has been like a school of craftsmanship, it was very particular.”

Were you able to use this experience, this knowledge, later on in your career?

“Yes, absolutely! Just think that in the studio we had a workshop where we made models for everything that we have done. Maybe also models that we made just for ourselves, so not the models that we showed to the public, but the ones made of paper, plaster, etcetera. In the workshop we made prototypes of everything. For lamps it was fundamental, because a lamp partly consists of a form, but partly of the light… We took a lightbulb and we tried if it worked, if it irritated the eyes. We had a large studio, with a lot of people, and the workshop was fundamental. D’Urbino in particular had golden hands, and he made models of everything.”

But despite the interesting environment of your grandfather’s company you chose architecture?

“Fortunately, otherwise I would have been a very bad small industrialist, the company would have gone bankrupt immediately [laughs].

I never graduated, I am one of the competent ones [A self-deprecating look]. I am in the company of Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe [laughs]. Everybody calls me architect, and every time when people call me architect I have to say I didn’t graduate, I’m an architect without a graduation, like the capimastri [in English: master builders—Palainco] of the past. We have made a lot of architecture, though.

I was close to the art world, I did some exams at the Accademia di Brera [Accademia di Belle Arti di Brera, art academy in Milan – Palainco], and then at a certain point I understood that I was very interested in light and space, which is architecture, and so I moved into that direction. I began to work very, very early, without a graduation, but very early. The first constructions I made before I met D’Urbino and De Pas, when I was very, very young.”

So at a young age you already realised what you wanted to do?

“Yes, above all there was one thing that I understood, which was that I didn’t know how to do anything else [laughs]!”

But you were talented?

“Well, talent is too big a word…, I liked it, and we had a lot of fun. Eravamo tre matti [We were three madmen—Palainco].”

-

Paolo Lomazzi and Carla Scolari in 1968 at home relaxing in Blow lounge chairs, designed by De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi for Zanotta. Picture by Toni Nicolini (source: L’archivio De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi, CASVA).

Paolo Lomazzi and Carla Scolari in 1968 at home relaxing in Blow lounge chairs, designed by De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi for Zanotta. Picture by Toni Nicolini (source: L’archivio De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi, CASVA).

-

At the beginning of his career Lomazzi collaborated with different other architects, for some time at the Milanese Studio BBPR, and later amongst others with his then wife, Carla Scolari. When they moved their studio to a different location, he was to meet his future partners, Jonathan De Pas and Donato D’Urbino.

“They had a studio in Via Rossini in an old and very beautiful house, that was called La Casa dei Pittori, because until the end of the nineteenth century it was filled with painters’ studios. And then my wife and I arrived, and we had our studio opposite their studio. We looked at each other, they looked at us especially, because my wife was very pretty. That’s how it started. They did mostly architecture, I on the other hand already did design. However, when you’re young architecture is difficult, especially because of all the paperwork, permits, bureaucracy, in short. Instead, design, especially in those years in Milan, was very lively, a bit like fashion. You needed to present things at the Salone [Salone del Mobile in Milan – Palainco] at a certain date, so the timeframes were short, and there was also a great folly.”

And now you are mainly known as a designer?

“I am not known. I have three surnames. As Lomazzi I am not known. People know me as De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi [laughs heartily].”

So making design was very attractive to an architect?

“Yes, attractive and entertaining; there were magazines, newspapers, press— it was a madness. The Salone del Mobile… It was a magical moment, I would say.”

Did you realise that at the time, or only afterwards?

“Not in the moment, at the time you never know anything. Of course, there was a great liveliness. We had discussions, every night, until late. Not just us, but with many others, the most intelligent and lively architects, young people. We discussed, we danced…

I had a studio across the courtyard on the first floor, De Pas and D’Urbino on the ground floor. During the day we walked up and down the stairs all day, and so we decided to go to a studio on Corso XXII Marzo, where we had one studio, with one secretary.”

-

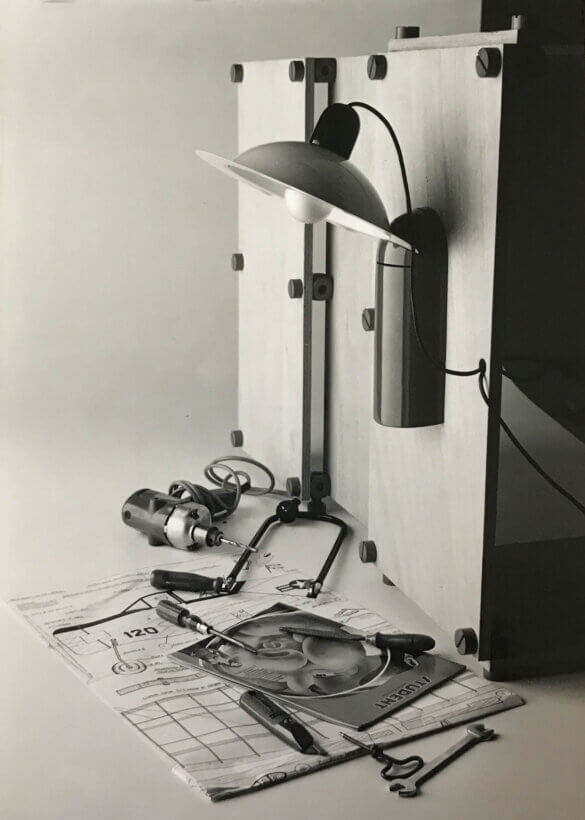

Multipla floor lamp, designed by De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi for Stilnovo. The lamp that is made of lacquered aluminium and a chromed tubular frame is fully swivelling. Picture from the original Stilnovo catalogue (from the Palainco archive).

Multipla floor lamp, designed by De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi for Stilnovo. The lamp that is made of lacquered aluminium and a chromed tubular frame is fully swivelling. Picture from the original Stilnovo catalogue (from the Palainco archive).

-

One of the first lamps that you made was Multipla, for Stilnovo.

“It has a story a bit different from the others, meaning that I had found a lamp in Switzerland, which I still have in the attic. They made this ‘hat’ for medical practices, for operations, etcetera. We studied the shape of the parabola, because it provided a perfect light. It began to go around in the studio, and we said: What shall we do with it? Under the hood there is a little cup, that reflects the light on the entire parabola and gives a very concentrated light, but it does this very, very well. In fact, subsequently in the studio the idea was born to make this support so that the hood could turn in all directions.

The idea came from a found object, which functioned very well. We said: let’s make it even better [laughs]. This way it became a pendant, it could be placed on the floor, and used as a wall lamp.

The idea always comes from somewhere. Designers aren’t inventors. For example, nowadays LED bulbs are a great innovation, with LED you can do extraordinary things. We then apply it and hopefully make intelligent lamps.”

How did you get in touch with Stilnovo?

“I don’t remember. I believe that they came to us. During the economic boom we designed some objects that were very symbolic, that were a bit unconventional. The lounge chair Blow, and Joe. We had a lot of visibility, so I think in this case they came to us and asked us to make something.”

“It was a model for life that was shared by all of us, otherwise we could never have worked together for fifty years or more. We camped, we had a boat, we all rode a bicycle, we dressed differently from others, we had long hair. So it was all part of a lifestyle. It was not about having a representative house; we had simple and humble homes with objects that we used. We started to create objects for our peers. We actually had a spirit close to the Dutch [laughs]. Eventually we had a model for life, that became a model for the house.

We didn’t make the objects that we made because there was a client who said to us: I need a lamp. We made them, because we encountered practical things in our lives. For example a chair that was very comfortable, so we said: Let’s make one that we think is more correct. Another important thing that is different from today: Now there is a great hyper specialisation in design. For us it’s been fun; we made a house, and when a sofa was needed and we didn’t like the sofas in the catalogues, we designed one. This type of ping-pong, not doing the same things over and over, but we went from one subject to another. It was very entertaining.”So you have worked a lot on the basis of your own ideas, and not on the basis of assignments?

“Not always, but often.”

That seems very beautiful?

“Yes, but from an economic point of view it’s better to have a client. It often happened that when we had an assignment, each of us tried their hand and wanted to be involved in the design. So in that respect it got very creative, hence our work became very creative, the type of work that we did. Apart from this kind of ping-pong, this going from one thing to another, we put our ideas on the table during our meetings, and when two had the majority, the third was left to cry. A very strong democracy. What did it mean? We didn’t work on the form, but on the concept. When you work alone, your work becomes more formal, concentrating on form, which is then repeated. But when you look at our work, you can see that the work is recognisable, but not because of its formality. There is a coherence to the design.

We discussed the design and very often we demolished it. We said: Why like this? Is it good? Is it useful? It’s too expensive. Just look: What an ugly form! Etcetera. But the next day, what one of us had rejected, the other picked up again. The transformation of an idea, which then became a synergy. Not regarding the form, but the content of the object, and this way it got better.”

Maybe that’s why your designs are still fresh?

“… [Pause] Thank you! [laughs] You know what’s very strange? That at the moment everyone is asking us about designs from the 60s and 70s. Tomorrow I will be at Zanotta, that wants to produce Blow, the inflatable chair, again. Right now everyone wants to make re-editions of things from those years. That is also a fashion. But it is clear that at that time those objects were somewhat symbolic objects, which were taken up by an elite. Now many things come into everyone’s house.”

-

Lampiatta wall lamp, designed by De Pas D'Urbino Lomazzi for Stilnovo. Picture by Rodolfo Facchini (source: L’archivio De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi, CASVA).

Picture below: Drawing of the Lampiatta table lamp designed by De Pas D'Urbino Lomazzi for Stilnovo from the original catalogue (from the Palainco archive).

Lampiatta wall lamp, designed by De Pas D'Urbino Lomazzi for Stilnovo. Picture by Rodolfo Facchini (source: L’archivio De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi, CASVA).

Picture below: Drawing of the Lampiatta table lamp designed by De Pas D'Urbino Lomazzi for Stilnovo from the original catalogue (from the Palainco archive).

-

The Lampiatta series that you did for Stilnovo seems simple, but is brilliant?

“It’s been reissued. Yes, it is one of the most beautiful objects. There are two separate objects, which you can apply many ways, for instance as a pendant or as a wall lamp, when turned upside down.

-

One of the things I like the most, I don’t say it’s the most beautiful, but always because of its simplicity and intelligence, is this one, Fante. It seems simple, but it is very studied. Here is the lamp holder in rubber and there are no screws, nothing. You can’t see this, but it’s a little rubber stamp [the body of the lamp—Palainco], it doesn’t damage the table top. The lamp holder sits inside by pressure, so there are no screws, etcetera. And then there is this little hat, you just move it. What could be simpler? And upside down, it becomes a ceiling lamp. You direct the light where you want it. This is an intelligent design.”

But to make something so simple, you must leave out a lot?

“Bravissima, that’s how it is.”

-

Fante table lamp, designed by De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi for Stilnovo. There was also a wall and a ceiling version of the model. The body was made of stamped rubber and the reflector of white lacquered metal. Picture from an original Stilnovo catalogue (from the Palainco archive).

Fante table lamp, designed by De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi for Stilnovo. There was also a wall and a ceiling version of the model. The body was made of stamped rubber and the reflector of white lacquered metal. Picture from an original Stilnovo catalogue (from the Palainco archive).

-

We sit in the spacious kitchen with windows overlooking the city, enjoying a glass of wine and some appetizers. After Jonathan De Pas’s death in 1991, Paolo Lomazzi continued working with Donato D’Urbino until they closed the studio a few years ago, after more than fifty years of working together. One of the more important exhibitions that the studio contributed to was “Italy: The New Domestic Landscape” that was held in 1972 in the MoMa in New York. It showed the achievements of modern Italian design at the time and meant a lot for the recognition of Italian design in the world.

Some of your designs were shown in New York at the time?

“Our pieces are in almost all museums of the world. We had about five or six objects at the MoMa. We wanted a mime artist to show and explain the objects, but I was very young and there was no money, and I didn’t have the capacity, the allure to convince him [Emilio Ambasz, curator of the exhibition – Palainco]. It was a very important exhibition for Italy and for design. He [Ambasz—Palainco] was a genius. And I was there.”

What was the experience like?

I felt like an Italian [laughs]. All those big Americans… The opening was in the winter, it was cold. I had a big glass of whiskey at six o’clock in the evening, I really felt like a little mouse. But it was interesting. I went there especially to see all those American artists, like Rauschenberg. So the experience was not only the exhibition, but also the tour that I did.

Was the trip inspiring?

“I was like a sponge, I was a little lost.”

-

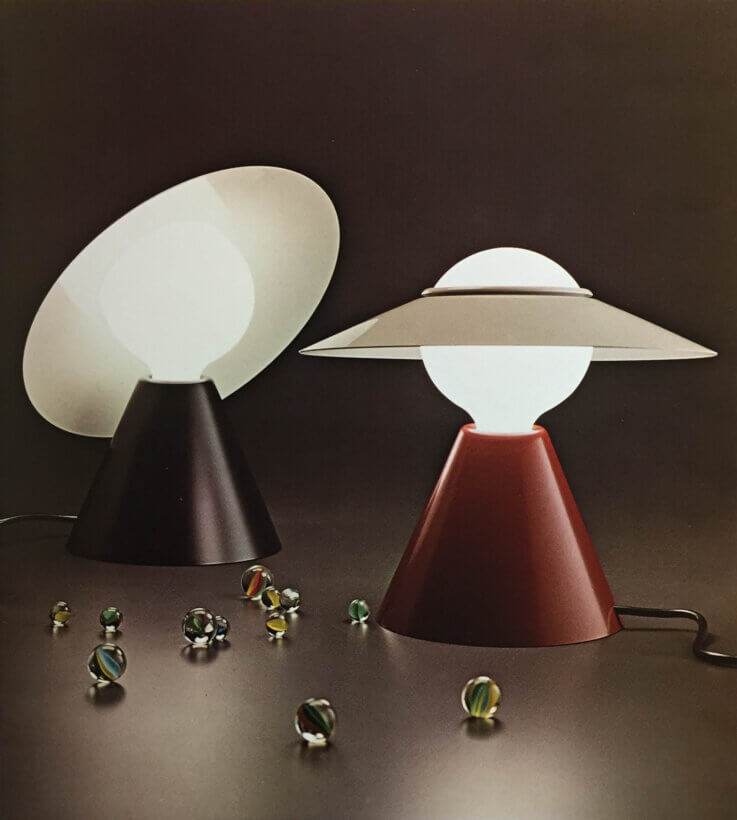

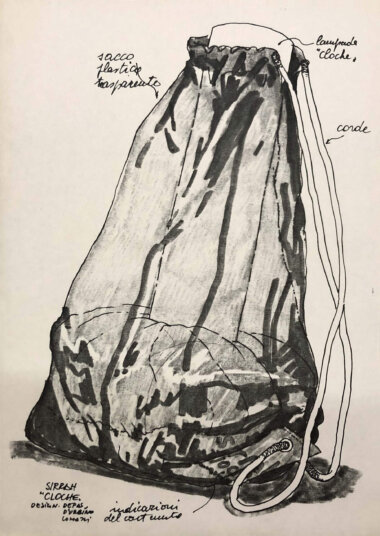

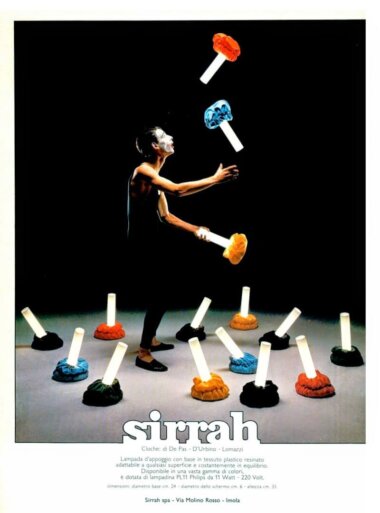

Picture left: Original drawing for Cloche table lamp, designed by De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi for Sirrah (source: L’archivio De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi, CASVA).

Picture right: Cloche table lamp, designed by De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi for Sirrah in an advertisement (from the Palainco archive).

Picture left: Original drawing for Cloche table lamp, designed by De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi for Sirrah (source: L’archivio De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi, CASVA).

Picture right: Cloche table lamp, designed by De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi for Sirrah in an advertisement (from the Palainco archive).

-

Gets up and fetches the table lamp Cloche that sits in the spacious kitchen, and puts it on the table.

“There is a story attached to this. There used to be these ashtrays that were made of a small leather bag filled with lead balls, like the ones you use for a shotgun, which are therefore heavy, with a small dish on it. You could place them on sofas, on the armrests. It was made by a good designer. The same with this lamp, that you can put anywhere.”

Maniglia, another model that you did for Stilnovo, was one of the first halogen lamps. Where did the idea come from?

“I don’t know, the idea was simple: a stick, very simple, with a light bulb with a handle on one side and the transformer on the other side for balance. The counterweight was the transformer, the essence.”

Who was the first to work on the idea of the handle?

“That was a very beautiful design by De Pas. He made very beautiful sketches. He had the capacity to draw almost automatically, with great ease.

He was a genius. An extraordinary person. He represented us. He had a great verbal capacity to express himself. He was the uomo pubblico [In English: the pr man – Palainco] of the studio. It is a pity that he passed away too soon.” [A look of emotion passes across his face.]

-

Picture left: Fiocco pendant, designed by De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi for Stilnovo, original picture (source: L’archivio De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi, CASVA).

Picture right: Drawing of the Fiocco lamp, designed by De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi for Stilnovo (source: L’archivio De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi, CASVA).

Picture left: Fiocco pendant, designed by De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi for Stilnovo, original picture (source: L’archivio De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi, CASVA).

Picture right: Drawing of the Fiocco lamp, designed by De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi for Stilnovo (source: L’archivio De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi, CASVA).

-

You also made Fiocco for Stilnovo. Was it designed for a special project?

“The idea was to do something for graphics. There is this metal grid from which you could hang a series of panels, for public spaces rather than houses, restaurants for example, to dampen sound waves. They reduce the noise a bit. They are made of a material that resembles fabric. Moreover, for example in travel agencies etcetera, they work with graphics… But it hasn’t had much success. But once, long ago during an Easter holiday, I went to the Caribbean and I flew in a small plane to a very small airport. And there was a whole installation above the counter, all dusty [laughs]. I thought: Do I have to come all the way here to see it! I had never seen it in Italy! Great, that sort of thing.”

You always had new ideas. Did they come naturally, or did you have to work on it?

“The more a person does, the more ideas he has. Furthermore, you get up in the morning, you brush your teeth. The toothbrush isn’t good—holy smoke!—so you design a new toothbrush. And from there everything arises. You design the toothbrush, the cup, the bottle.”

So you need to be very conscious of your surroundings?

“Also subconsciously perhaps, but in any case with the will to be curious. When you grab your pencil, you think: Why don’t you do it like this? Maybe you are wrong a hundred times, but still…

-

Sidone pendant, designed by De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi for Artemide, executed in metal and chrome with adjustable rods with an upward diffused and a downward concentrated light. Picture from the Artemide catalogue (from the Palainco archive).

Sidone pendant, designed by De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi for Artemide, executed in metal and chrome with adjustable rods with an upward diffused and a downward concentrated light. Picture from the Artemide catalogue (from the Palainco archive).

-

[Gets up and fetches pendant Sidone, produced by Artemide]. This lamp seems simple, but is very studied. It’s a 500W lamp, very strong, there is a glass above it, it projects the light upwards and downwards with concentrated light on the work surface without obstructing the view. So when you sit, it doesn’t dazzle your sight, when you look into it. Here are rods which you can make longer. This is one of the objects that is well made. Well made and well studied.”

Perhaps you can say something about the collaborations with producers – were they always constructive?

“I must say that especially with Artemide, with Gismondi, [Ernesto Gismondi, the founder of Artemide – Palainco] it wasn’t easy to work. It was a shame, because it was a very important company, but he had a very strong character, a bit prepotente [in English: overbearing – Palainco], so there wasn’t a great feeling with us. That’s very important when you meet.

Our history, by the way, within the history of design has this characteristic. Our generation started working early, we were among the first. We worked with companies that were closer to being artigiani [In English: craftsmen – Palainco], in the beginning. They have grown with us. At BBB Bonacina we didn’t make one piece, we did a lot, and also for Zanotta, etcetera. They’re all companies that started out as artigiani, and then they presented things that were successful, and the success caused the arrival of other requests. That collaboration was very intense and very strong, and it has brought remarkable results. At one point they trusted our judgement, and they trusted us. Nowadays, for young people the world has completely changed. It is not like that anymore. At the time, the producers were intelligent people, but they had no preparation. They were culturally ill prepared, but they were all very intelligent individuals with a spirito di fare [In English: entrepreneurial spirit – Palainco].

-

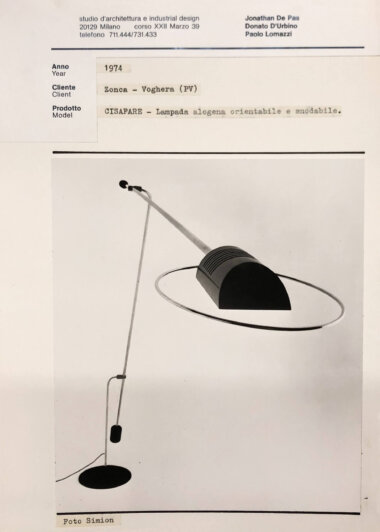

Cisafare floor lamp, designed De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi for Zonca. Original file from the Studio, picture by Simion (source: L’archivio De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi, CASVA).

Cisafare floor lamp, designed De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi for Zonca. Original file from the Studio, picture by Simion (source: L’archivio De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi, CASVA).

A lesser-known model is Cisafare, that you have created for Zonca.

“It’s wonderful. It’s not made of anything. It was big, you know. As big as Castiglioni’s [Arco, floor lamp by Achille Castiglioni for Flos – Palainco], it’s not a table lamp. That company made period lamps, tipo ottocento [In English: nineteenth century – Palainco]. Then they came to us to make this stuff and we made one, but they didn’t go any further, like Stilnovo did; they first made those lamps a bit déco, but then they started working with designers. In fact, this may have been a little forward for them, but that’s just the way they were.”

When did you feel satisfied about a design?

“In our profession, you could always do more in the end. I especially am very critical. I’d like to throw it away and make something new.“

But having that will is beautiful, isn’t it?

“Yes, because that’s how it keeps moving. To have such a list of lamps means that

-

a thousand designs have been made. They have remained on paper and there may be some very nice ones among them. That’s our job.”

You have closed the studio, but you are still active and you don’t seem retired to me.

“No, I’m not retired. Life has changed, because it didn’t make sense anymore, because we had a very large studio. We arguably had the largest design studio in Milan. Without external employees, we were fifteen people or more. Usually, studios have two people. In the end, instead of working at big design tables, we had computers and a big room that was difficult to heat. Now someone can do the work at home on a computer… There was no point anymore. Apart from the fact that we have grown old and everything has changed, but the will to design is not lacking [laughs].”

-

Paolo Lomazzi (left) with Donato D’Urbino (right) in their studio at the Corso XXII Marzo in Milan (source: L’archivio De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi, CASVA).

Paolo Lomazzi (left) with Donato D’Urbino (right) in their studio at the Corso XXII Marzo in Milan (source: L’archivio De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi, CASVA).

-

“We had a direct relationship with everyone, also abroad. We have collaborated for example with Ligne Roset. They picked us up from the airport and took us to the company. Meanwhile we talked about work and other things, like politics. So, there was a very strong human relationship. And now I have a relationship with Zanotta, but now I don’t talk to the owner anymore, I talk to the technical department, so my ideas don’t arrive where they should. That’s a big change, I think.

The industry, when it gets big, has someone that takes care of the business side, and they don’t have time to deal with products. But we took our time, like we did with Zanotta once a week –I remember it well— because that’s how it went on for many years, on Thursday morning I went to Nova Milanese. He [Aurelio Zanotta, the founder of Zanotta—Palainco] picked me up and didn’t let go of me. When it was evening, I was dead tired. He would then say: “Why, Paolino, come home with me.” His wife’s name was Nora, “Let’s go to Nora, she will make us due spaghetti.” I made his house, the settlements, the houses of the children, of his brothers. We were two comrades. We argued terribly. He was a strong man, he said holding his fists like this [clenching his fists], “Sono io che comando!”. [In English: I’m the one in charge here!— Palainco]. The next day he would write me a card: “Sorry Paolo…”. He took part in projects, when I brought him a drawing it wasn’t mine anymore, but it became hís project. We discussed everything like equals. With great respect. However, today, the world… In short, we have interpreted a historical moment.”

-

- Palainco would like to thank : Paolo Lomazzi, for sharing his passion with us.

- We would also like to thank : Elisabetta Pernich, Caterina Zeffiro and Guia Campiglio (CASVA Milano).

Unless otherwise stated, all material is sourced and/or generated internally. All rights reserved.

- Text: Palainco, Koos Logger & Ingrid Stadler.

- Image sources: L’archivio De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi (CASVA Milano) and the Palainco archive.

The article and its contents may not be copied or reproduced in any part or form without the prior written permission of the copyright holders.

Published on: 2 December 2022