“You need to remove the fantasy from design. Design is tied to reality.”

- An interview with Donato D'Urbino

We are in Milan and spring is in the air. Being a little early for our appointment with Donato D’Urbino, his wife—who arrives at the same time—addresses us in the street to say her husband is expecting us on the eighth floor. Architect Donato D’Urbino spent most of his career working with Jonathan De Pas and Paolo Lomazzi, in the innovative and multi-award winning trio Studio De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi. In 2018, D’Urbino received Italy’s most important design award, a Compasso D’Oro, for his successful career (after he received one in the 1970s for his clothes hanger Sciangai). He receives us in his home where we notice a recent prototype for a new lamp on the ceiling of his living room. The walls are covered with bookshelves and paintings made by his father and his grandfather.

A sketchbook and a pencil at hand, as well as a list that he made with Paolo Lomazzi with no fewer than 38 lamps created by Studio De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi, Donato D’Urbino is ready to answer our questions. The following interview was translated from Italian.

-

“You know, we only made it just now, we never thought it would be necessary to make such a list. We made it in the past few days, after we got your email.”

You really made a lot of lamps.

“Yes, but a handful of them are not so interesting. And there are also some in the CASVA archive [in Milan—Palainco], which have not been produced.”

-

A prototype of the Seven table lamp, designed by De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi for iGuzzini. Unfortunately the model was never taken into production (source: L’archivio De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi, CASVA). Picture above: Donato D’Urbino with his beloved Valentina table lamp from his private collection, that was designed by De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi and produced by Valenti (picture by Palainco).

A prototype of the Seven table lamp, designed by De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi for iGuzzini. Unfortunately the model was never taken into production (source: L’archivio De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi, CASVA). Picture above: Donato D’Urbino with his beloved Valentina table lamp from his private collection, that was designed by De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi and produced by Valenti (picture by Palainco).

-

Like this one for iGuzzini, Seven?

“Seven, yes, mi piaceva da matti, I loved it. I don’t know why it wasn’t successful. It is based on a simple bent plate. It is not the only DDL project to fail to materialize.”

[We show him a picture of table lamp Ibis.] Harvey Guzzini did produce this one though…

[With a cry of recognition:] “Aaaah! Now I remember…”

What do you think of it?

[He hovers his hand barely above the floor, so as to indicate a low level.] “I will remain silent.”

You don’t like it?

“No, I don’t like it, I prefer not to elaborate.”

[While looking at some pictures of Ibis.] “Ah, I don’t like it, I don’t like it… Now I remember, I never liked it.” [He laughs.]

Lomazzi told us: “If I could, I would change it.”

“Ah!” [laughs], “he too has criticisms!”

-

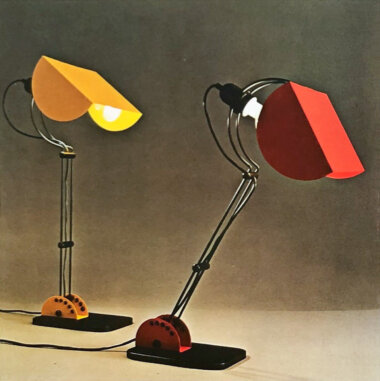

Wall version of the Lampiatta lamp, designed by De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi, with a body in ABS and a multi-positionable reflector in white lacquered metal. Picture from an original Stilnovo catalogue (from the Palainco archive).

Below: Ibis table lamps designed by De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi for iGuzzini as published in a leaflet by the company (source: L’archivio De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi, CASVA).

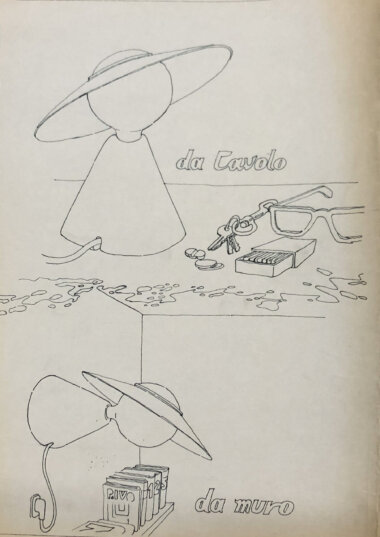

Bottom picture: Drawing of the Fante table and wall lamps, that were designed by De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi for Stilnovo (source: L’archivio De Pas, D’Urbino, Lomazzi CASVA).

Wall version of the Lampiatta lamp, designed by De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi, with a body in ABS and a multi-positionable reflector in white lacquered metal. Picture from an original Stilnovo catalogue (from the Palainco archive).

Below: Ibis table lamps designed by De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi for iGuzzini as published in a leaflet by the company (source: L’archivio De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi, CASVA).

Bottom picture: Drawing of the Fante table and wall lamps, that were designed by De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi for Stilnovo (source: L’archivio De Pas, D’Urbino, Lomazzi CASVA).

-

[He looks at his list of lamps.] Stilnovo was a great company, but it doesn’t exist anymore. There is a different company that has chosen to make two of our lamps: Lampiatta and Fante. They have chosen very well; these lamps are quite important. Both are very simple: Fante uses the sphere of the lamp to direct the light from one point to another. Lampiatta has no hinges, there are no strange mechanisms, you pick it up and put it in different positions. They are two of the most important lamps that we have made. Not all our lamps are as successful as those two.”

-

-

Lampiatta is a very pleasant object, also when it’s not switched on?

“Yes, that is important. While the one by Guzzini [model Ibis—Palainco], doesn’t have that ability. It is complicated. Now I’m self-critical”

Maybe it’s a strange object?

“It’s the kind of strange that is a bit gratuitous.

Another lamp with the same characteristics of simplicity [as Lampiatta—Palainco] is Lampenudo.” -

Fluorescent Lampenudo pendant, designed by De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi and produced by Candle. According to Donato D’Urbino it is “one of the most beautiful things” (picture by Aldo Ballo, source: L’archivio De Pas, D’Urbino, Lomazzi, CASVA).

Fluorescent Lampenudo pendant, designed by De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi and produced by Candle. According to Donato D’Urbino it is “one of the most beautiful things” (picture by Aldo Ballo, source: L’archivio De Pas, D’Urbino, Lomazzi, CASVA).

-

Do you like Lampenudo?

“Yesss… very much. It’s one of the most beautiful things.”

Why do you like it so much?

“Because it’s nudo [bare, nude–Palainco], it is essential, it can’t be more simple.”

When a design is simple, it probably means that a lot of work is spent to achieve the simple result?

“Yes, that’s true. To achieve simplicity, you need to take away, to reduce it to its basic elements…”

We sit at the dining table with a view of the lively yellow kitchen with some homemade designs, like a bread board that also collects the crumbs, and a holder to always keep a nutcracker within reach. After Jonathan De Pas’s death in 1991, Donato D’Urbino continued working with Paolo Lomazzi until they closed the studio in 2017, after more than fifty years of working together.

“Our meeting was accidental. De Pas and I had already opened our studio when in the same building, on the same courtyard Lomazzi arrived with his wife [Carla Scolari— Palainco], who was an architect as well. The first days we looked at each other, the competition… [he pronounces the word competition with emphasis, mockingly].

Slowly we came to a shared vision about the work. Lomazzi got divorced, then another character, Decursu, came to work with us for a short time. So, the formation of the group didn’t happen right away, it came together slowly.” -

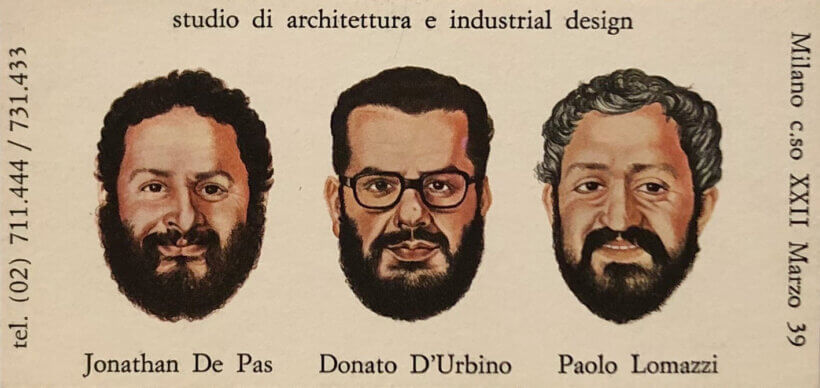

Businesscard used by De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi, implicitly emphasizing that all work was signed by the trio (source: L’archivio De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi, CASVA).

Businesscard used by De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi, implicitly emphasizing that all work was signed by the trio (source: L’archivio De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi, CASVA).

-

What did you have in common when you started working together, was it an attitude, or did you have the same aspirations?

“At first, we had a lot of confrontations about our ideas. Slowly we understood that we wanted to design simple products, elementary things. We wanted to create objects for the home that were all different from the things in our parents’ homes. We wanted to tailor our work to a young audience. Our parents had objects that were very important, handcrafted things. We wanted to make objects for the houses of young people, simple things that were easy to use. And not only that, but that were also simple to move. Young people are not attached to a home for life. People travel and move more, someone living in Milan can at a certain moment live in America. We always chose to make simple things, that are flexible, easy to fold and to ship. Also, things that were easy to transform, that had more applications. Do you see this table? [He walks to a coffee table in the living room.] You turn the tabletop… and slowly it becomes a dining table. This is just an example. We made many foldable things, which forced us to design with a lot of geometry. It was very necessary to know the depths of geometry. If an object needs to be transformable in two different applications, it needs to be geometrically controlled. That was my personal choice, my passion, geometry.

My father was an architect and an accomplished painter. I have many of his works.” [He shows us the considerable quantity of watercolours in his living room made by his father, Manfredo D’Urbino.]

Since your father was an architect, you were probably aware of what being an architect was about?

“I knew it and I often criticised his work, but I learned a lot from him. I studied architecture, but at the end of my studies I decided to focus on design. It also was a coincidence, because De Pas, who was four years older than me, worked in a very famous design studio, Nizzoli. When I had to write my thesis, I wrote it about the work of Nizzoli. That’s where my love for design started.”

Why did you want to work with De Pas?

“De Pas was a school friend of my brother’s, so we already knew each other. The first architecture job I had to do was very demanding, and as a young student I lacked confidence. I thought: perhaps I can do it together with De Pas, so we can help each other.

We were very young, and for us this period was very beautiful. Before these years design almost didn’t exist, there were only few designers. There was Nizzoli, and only a few others. Nizzoli wasn’t a designer in the literal sense, this line of work didn’t exist yet, he was a painter. Immediately after the war he started to work for Olivetti. He made very beautiful things. I worked in his studio. He was so famous that he got many architecture assignments despite his lack of experience as an architect. So, De Pas and I were sent to his studio to develop the projects that required an architect’s approach. He did many important things, for Olivetti he made typewriters, and he made sewing machines for other companies. But for us it was important to work in his studio, because he was in touch with a model maker, a very good one, his name was Sacchi [Giovanni Sacchi, a famous modeller—Palainco]. So, we got to know this Sacchi, and we visited his workplace, where we had the opportunity to learn many things”.

This seems very useful for a designer?

“Perbacco! [By Jove!] Sacchi worked with wood, he was very good at it. He had five or six collaborators and a big space with working tables. I admired his skill to work the wood with machines, as well as by hand, using tools. [He goes to the kitchen to fetch a wooden object.] Do you see this? Sacchi had made a test model in wood for Stilnovo, it wasn’t a lamp, and in the studio this piece of unfinished wood remained. I worked on it, as I had learned from him. This piece of wood is from Sacchi’s workplace. [From the way he holds it it is clearly a cherished object.]

Lomazzi told us that you have “golden hands.”

[At this, D’Urbino laughs.]

-

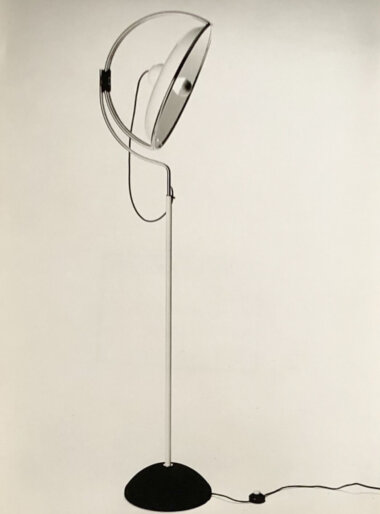

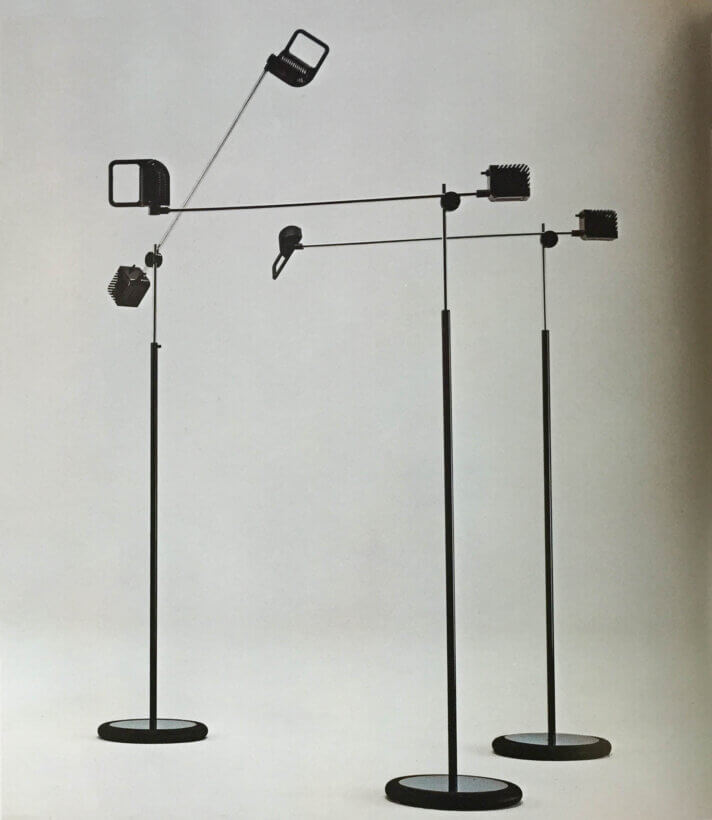

Multipla floor lamp (left) and wall lamp (right) in lacquered aluminium with a chromed tubular frame, designed by De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi for Stilnovo. The reflector can be swivelled in all directions (both original pictures, source: L’archivio De Pas, D’Urbino, Lomazzi CASVA).

Multipla floor lamp (left) and wall lamp (right) in lacquered aluminium with a chromed tubular frame, designed by De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi for Stilnovo. The reflector can be swivelled in all directions (both original pictures, source: L’archivio De Pas, D’Urbino, Lomazzi CASVA).

-

Another lamp that you did for Stilnovo was Multipla.

“It’s a beautiful lamp. The idea was that it could turn in every way, without a hinge. You could move it like this and to the other side. The idea was to attain this flexibility in use.”

Does it please you aesthetically?

“It is a very beautiful lamp.”

Were you involved in all projects that the studio worked on?

“We always all three of us signed the designs. We all agreed, each person bringing their contribution to the finished product, but then each continued with the project he was working on. Sometimes a design also passed from hand to hand.

There were also times when we didn’t all agree. Then there was someone pushing, and someone pulling. Sometimes it happened during discussions that the one who was against the idea, suddenly became supportive of it [laughs]. It happened. I remember a children’s chair, that caused a lot of debate. When it was finished, one or two years later, we all really appreciated the work.

There was not always total participation: there was someone who listened and expressed their opinion, and there was someone who listened but was concerned with other things. Because a collective studio produces revenue for three people, not just one. So it makes sense that there are several roads that each of us has taken. But it was very pleasant.”

When did you understand that this way of working was very important?

“From day one, for sure. I don’t believe there are many studios where three people are working together. I don’t know any other. I may know one with two elements, but not three. It’s difficult to strike a balance, but it was also our strength.”

Lomazzi told us: I am unknown as a designer; I have three surnames…

It happened that a French company invited us to see the factory, and when the person saw us he was amazed: De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi turned out to be three people!” [D’Urbino laughs heartily.]

What kind of a person was De Pas, what strengths did he have?

“A nice question. De Pas was a very intelligent character. I’d say very creative, but also someone to be held in check [laughs]. Lui andava per tangenti, he took strange turns, but in the studio he was a very useful character as a collaborator, because he always managed to come up with ideas that were extraordinary, unknown, not standard. It helped a lot.

And he was also very important to us, because he was very present everywhere. He had a pencil in his hand, but at six o’clock he would drop the pencil and go out to socialise. He didn’t take care of public relations like those who did it for a profession, but he was very curious, so he kept going out and he knew a lot of people. He was very useful for that as well. He did it spontaneously.

[While looking at a drawing made by Jonathan De Pas:] This pencil drawing, beautiful. De Pas drew da matti [like crazy—Palainco], he had a mano felice [a happy hand—Palainco]. I also drew a lot.”

-

Sidone suspension lamp with an upward diffused light and a downward concentrated flow of light, as published in the original Artemide catalogue. Design by De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi for Artemide (from the Palainco archive).

Sidone suspension lamp with an upward diffused light and a downward concentrated flow of light, as published in the original Artemide catalogue. Design by De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi for Artemide (from the Palainco archive).

-

[Looking at a picture of the pendant Sidone, produced by Artemide]. This one is very beautiful.”

Why do you like it?

“Because it has double lighting, aimed both upwards and downwards. The light gets on the table, but it doesn’t completely obscure the top. That’s very intelligent.”

Where did the idea come from, to let the light shine upwards as well?

“There was a physical reason for this. Do you envision what happens when you watch television? You should always have light around it. Your eye when it moves the gaze is looking at the darkness. It makes it difficult to see. So it’s important to have a double lighting, strong on the table, and weak on the rest. There is a practical and a technical reason behind it. That’s where the idea comes from.

In essence, ideas in the field of design can come in different ways. What you need to take away is the fantasy from design. It needs intelligence, creativity and flexibility. Design is tied to reality, not fantasy. [He slaps the table, as if to reinforce his words.]

For example, an idea can come from a new material. We worked a lot with padded furniture, because this material, polyurethane foam, had come out and made new processings possible, new shapes, and that immediately excited us. We have worked a lot with it. Many ideas came also from daily observations, as we observed things that were not functioning well.”

-

From left to right: Jonathan De Pas, Paolo Lomazzi and Donato D’Urbino with the Sciangai clothes stand, for which they received a Compasso d’Oro in 1979 (source: L’archivio De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi, CASVA).

From left to right: Jonathan De Pas, Paolo Lomazzi and Donato D’Urbino with the Sciangai clothes stand, for which they received a Compasso d’Oro in 1979 (source: L’archivio De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi, CASVA).

-

What did it mean to you to be a designer in the 1960s and 1970s? Designers wanted to change the world, society, the way of life.

“Brava, that’s exactly how it was. We also thought we could change society, but this didn’t happen.” [He laughs.]

How did you want to change society, in what sense?

“By designing rigorously, in a serious, concrete manner. A manner of leading the way for the development of society. But then we were ignored.” [He laughs.].”

Not quite…

“Not quite, but the world has become more and more complicated, and not simpler.”

So, you failed…

“…to make an impact.

We have always worked in the workshop. We were craftsmen, but not in the literal sense, artigiani del design. Real craftsmen are engaged in making things. We tried to design, but we were craftsmen of a different kind. Our thought was always linked to creativity, but no more than a good craftsman could do.”

Can you describe how the design process went?

“We worked around a table, on which we put our ideas. Before we talked about our ideas, we made a drawing. We always discussed a drawing. It happened that the drawing was not enough, and then we asked a collaborator to develop and clarify the concept. The first idea would come back to the table, and everyone would start to shoot at it, and gave their opinion. That’s how we took things further. It was also a difficulty, because all those meetings took a lot of time, and made the work harder. On one hand you used your neighbour’s creativity, on the other hand you thought: Today I’m busy, I have to do something else. It was quite demanding. Over time we became so united that each one of us could always guess the ideas of the others. We shared the idea to such an extent that it was no longer necessary to meet. When De Pas passed away, the two of us remained. The dynamic of discussions became much easier.”

A lot of designers work at the request of a company, but you have also done many projects…

“…because there was an idea.”

That seems ideal for a designer, and maybe it’s more interesting?

“In the studio we lacked a salesperson. We always worked locked up in the studio, and many projects stayed there, because rarely any of us had the patience to present an idea to a producer. Those inflatable objects were ours, we took them to producer Zanotta, who was immediately enthusiastic and went to work. That was a happy road. But not everything went like that. If you look at the CASVA archive, there are a lot of works that have remained there.”

Lomazzi told us that someone came by every now and then, from different companies, to see if you could work together?

“Yes, that happened after we made the Blow lounge chair. Producers understood that we had this creativity and came to see if we could do other work.

This way of working is very different from working in architecture, because when you do beautiful things in the design sector, intelligent things, and they are in exhibitions, shops and magazines, the public, the industrialist, the likely customers understand that you have capabilities. And that’s why they turned to us. This rarely happens in architecture.”

-

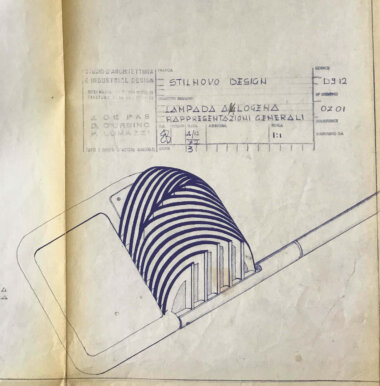

Swivelling floor lamp Maniglia (top picture) and a drawing of the reflector (picture above) designed by De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi. The arm of the lamps is in chromed metal and the reflector and transformer holder are made of Makrolon (source picture: Stilnovo catalogue, from the Palainco archive. Source drawing: L’archivio De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi, CASVA).

Swivelling floor lamp Maniglia (top picture) and a drawing of the reflector (picture above) designed by De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi. The arm of the lamps is in chromed metal and the reflector and transformer holder are made of Makrolon (source picture: Stilnovo catalogue, from the Palainco archive. Source drawing: L’archivio De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi, CASVA).

-

-

Another model that you made for Stilnovo was Maniglia. Do you like it?

“Yes, Maniglia is very beautiful. Maniglia got that name because the head of the lamp had a handle. [He draws the head of the lamp for us.] Maniglia was a fairly simple model, which subsequently gave us the desire to make it more user-friendly. And that’s why Valentina was born. Maniglia is a very beautiful object that has aroused the desire to do even more.”

-

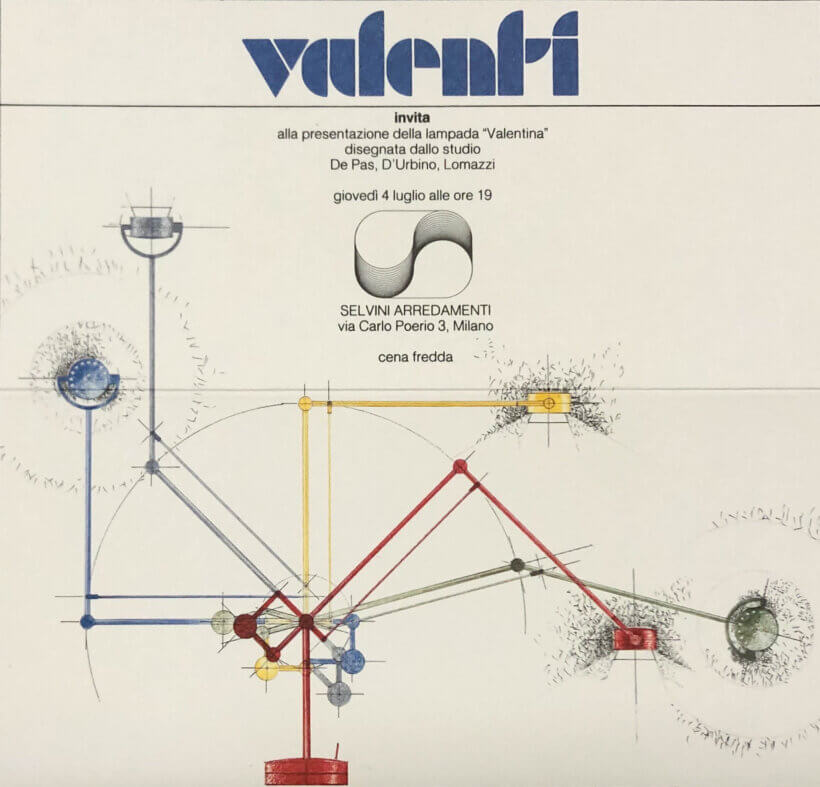

Picture above: Invitation for the official presentation of the Valentina (source: L’archivio De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi, CASVA).

Picture below, left: A wooden prototype made by Donato D’Urbino of the Valentina table lamp, that was designed by De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi for Valenti (source: L’archivio De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi, CASVA. Picture by Palainco).

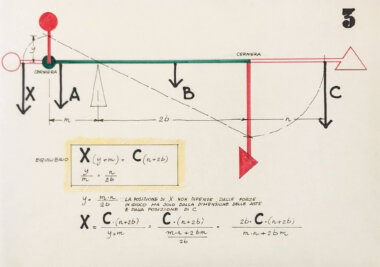

Picture below, right: Formula used to reach optimal balance (source: L’archivio De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi, CASVA).

Picture above: Invitation for the official presentation of the Valentina (source: L’archivio De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi, CASVA).

Picture below, left: A wooden prototype made by Donato D’Urbino of the Valentina table lamp, that was designed by De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi for Valenti (source: L’archivio De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi, CASVA. Picture by Palainco).

Picture below, right: Formula used to reach optimal balance (source: L’archivio De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi, CASVA).

-

-

Before this interview Donato D’Urbino wrote to us that he would like to talk especially about the Valentina table lamp that was produced by Valenti. It is very dear to him, since he decided to record all the stages of the design process.

Let’s talk about Valentina…

“Oh! [looks delighted]. It’s my passion [Goes downstairs to get the Valentina table lamp produced by Valenti and puts in on the table.] There it is! It’s been more than 35 years.

The lamp can stay wherever you put it and will always keep the balance, in any position. That’s why I wanted to talk about Valentina, because Valentina’s project has been photographed in all its stages, something we’ve never done before. It is thus a documentation of the method of the design. If you’re patient, I’ll show you on the computer.”

Why did you record the whole process?

“Normally when you design, the project progresses gradually, and you throw away the old material. But this time we had the intuition that it could be an interesting story. That’s why we registered everything. Come sit here for a second.” [We sit at his computer and he shows us all stages of the design of Valentina table lamp.]

This is the origin, it’s an old lamp that we had in the studio that has a hinge at the top. Every time you moved the lamp it fell over [laughs]. We said: This is not good; we need to make a lamp that will stay in whatever position we put it in.

These things are also easy for you to understand, because we have the finished lamp in front of us. But when we started, we didn’t know what would emerge. Realizing that stability would be an issue took a while.”

Have you always designed this way?

“That’s why I wanted to show it, because the process is interesting. Oddio… [Oh God…], of course there have been things that have come about in a shorter amount of time, but this is one of the most interesting things.”

Have you always gone to the company to check the process? Otherwise, someone might say to you: We can’t do it like this, let’s do it like this?

“Perbacco! That’s how it was, but the owner was so enthusiastic about this object that he devoted a lot of time to it.

You learn a lot this way, because the producer in the company knows more about it than we do, so we make suggestions, but after that comes the discussion.”This reminds me that a designer also has to be patient? You cannot think: “this is the design and in a few days we will move on?”

“Perfect, you must print this! That’s exactly how it is [laughs].”

When does a design satisfy you?

“I’m satisfied when the initial idea eventually becomes an object that works. Did you see that there was an idea at the beginning, the will to make a well-made object. And when it’s over, I am satisfied.”

Perhaps the best part is that you are still working on projects and ideas?

“Yes, but without the studio it’s difficult.”

But your brain still continues with it?

“Yes, it’s a disease [laughs].”

Do you work every day?

“Well, look, inventing things, that’s why I say it’s a disease, never ends.”

That’s beautiful, isn’t it?

“Yes. When I look around, I see so many things that I can do. I have a workshop, a hundred meters from here, in a garage. It is completely full, there is no room for bicycles.”

So you never stop?

“No, it’s bellissimo.”

It seems more like a way of life than a profession, or a craft?

“Bravissima. Of course, when products are made in a factory there is a greater satisfaction, but it’s not necessary. You can also have fun and be fulfilled by designing and making models.”

As we are approaching the end of the interview, there is another question that D’Urbino himself would like to answer:

“You forgot to ask me a question that you wrote to me.”

Which question do you mean?

“The question ‘What do you think of the current state of design?’

What has happened in architecture, is now happening in design. In architecture there were the maestri, individuals like Alvar Aalto, Mies van der Rohe, etcetera. Those belonging of that era, who founded modern architecture. What happened afterwards, because of the success of these individuals? Others have discovered design, its simplicity and all those things, but they have done it in a less cultured manner. This has happened to everything, the design market, the product market has expanded like crazy. So, if you, like I did the other day because I’m planning to design one, look for what’s already been made in the field of a mezzaluna [chopping knife], you will find an incredible number of items. All modern, none of them particular, let’s say that they copy them from each other. The origin of this huge abundance is that there are many companies doing the same thing. They need to distinguish themselves from the others and find their corner of the market. So, the market is flooded with products that are called design, but that are not design. And that’s the situation. I’m not saying that design is dead, because it isn’t, because there are still beautiful and interesting things, especially with the new technology and electronics. But it’s not the same anymore.”

If you would like to be the first to read articles on designers and special designs, please subscribe to our newsletter.

-

- Palainco would like to thank : Donato D’Urbino, for his dedicated collaboration, for which we are very thankful.

- We would also like to thank: Elisabetta Pernich, Caterina Zeffiro and Guia Campiglio (CASVA Milano).

Unless otherwise stated, all material is sourced and/or generated internally. All rights reserved.

- Text: Palainco, Koos Logger & Ingrid Stadler.

- Image sources: L’archivio De Pas D’Urbino Lomazzi (CASVA Milano) and the Palainco archive.

The article and its contents may not be copied or reproduced in any part or form without the prior written permission of the copyright holders.

Published on: 27 October 2022