“It’s all chemistry” — Fulvio Ferrari’s little-known avant garde lamps

Interview

During a magical period for Italian design at the beginning of the 1970s, Fulvio Ferrari started to create wonderful avant garde lamps for his company Solka B, which was one of the small craft companies in Italy producing lighting. Now well-known as an expert on the works of Carlo Mollino and Ettore Sottsass, we asked Ferrari to look back with us on a period when fascinating, rare lighting objects were born.

For our interview, Fulvio Ferrari took us to his favorite gastronomia in Turin and afterwards to Museo Casa Mollino, where we sat overlooking the river. He let us probe him with questions, while he opened box after box of pictures and sketches of his work. The following interview was translated from Italian.

-

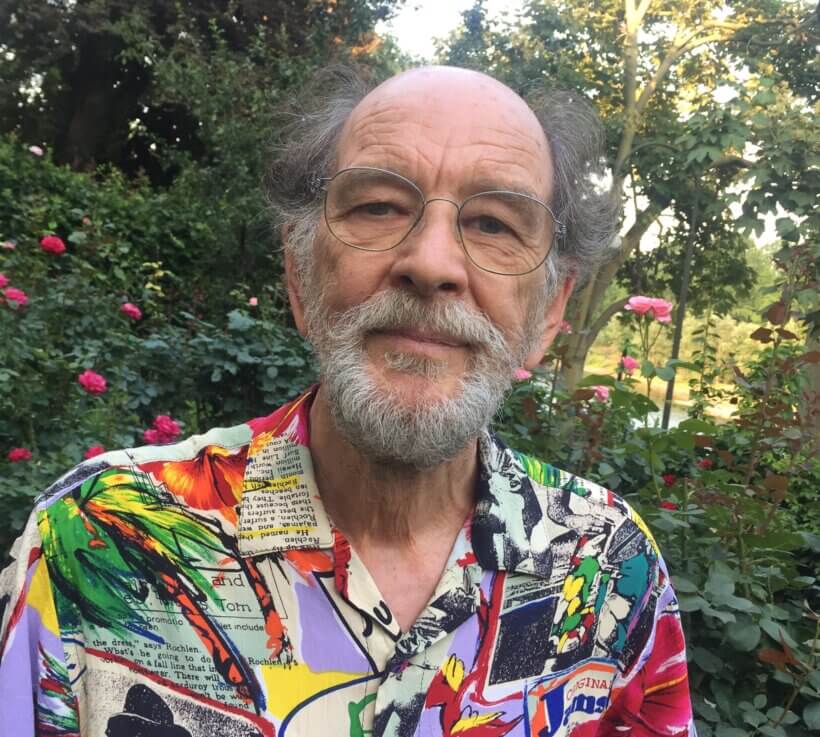

Fulvio Ferrari in the garden of Casa Mollino in Torino in 2017. Picture above: Fulvio Ferrari with the Molecola lamp from Palainco's private collection (Pictures by Palainco).

Fulvio Ferrari in the garden of Casa Mollino in Torino in 2017. Picture above: Fulvio Ferrari with the Molecola lamp from Palainco's private collection (Pictures by Palainco).

-

You are known as an author specialising in the works of Carlo Mollino, Ettore Sottsass, of Italian illumination at the end of the 1960s and the early 1970s, but are you also known as the founder of Solka B?

“Very rarely, because there are no documents of Solka B on the internet and also not on paper. It was a company that existed for a short time only, as a craft company. It was not a business that somebody invested money in and then would do a lot of publicity, like for example Flos did. Documents of Solka B hardly exist, it’s not a history that is known.” -

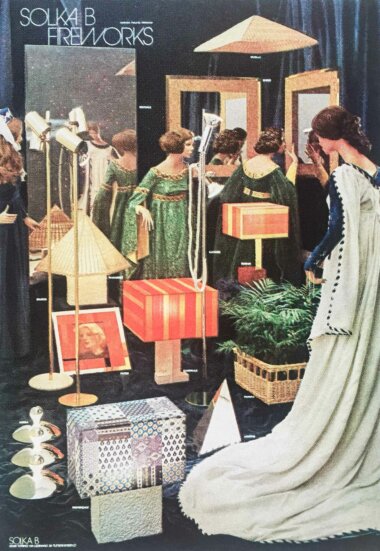

Solka B 'Fireworks' catalogue, 1970s (source: Pubblicità in Italia 74/1975, Editrice l'Ufficio Moderno), picture by Giulio Tua.

Solka B 'Fireworks' catalogue, 1970s (source: Pubblicità in Italia 74/1975, Editrice l'Ufficio Moderno), picture by Giulio Tua.

As a young man, Ferrari drew inspiration from the laboratory where his elder brother worked at as a chemist. The strange world of a chemical laboratory seemed very interesting to him, he perceived it as a sort of augmented reality. After he studied chemistry, he started working in a paper mill, like his father and grandfather had done before him. The world of big machines at the paper mill and a later job as a chemist at a petrochemical factory both inspired him to create his first art works.

-

“I got involved in the sector of petrochemical industry, and this world was like a drug to me—without having to take anything. If you are ready, it takes you out of this reality and shows you a different one. A different reality helps you understand that you live among a series of endless things that maybe are right in front of your eyes or before your feet, but you are not aware of them.”

“From that type of vision, and also from the intent to continue to see things differently, I had developed a special mode that opened the door to … art. My first step was to start using materials that were used by the companies that I worked for to make real works of art.”

-

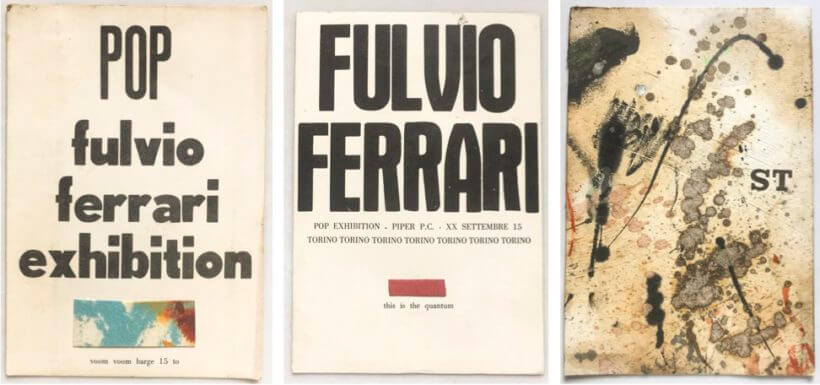

Invitations for exhibitions of Ferrari’s work in the late 1960s (left & center) and an artwork by Fulvio Ferrari (right) (source: Fulvio Ferrari).

Invitations for exhibitions of Ferrari’s work in the late 1960s (left & center) and an artwork by Fulvio Ferrari (right) (source: Fulvio Ferrari).

-

Do you still have examples of your early work?

“I always had an interest in environments that were out of the ordinary. So I organised exhibitions of my works, but not in galleries that I did not really like, but in places where—in my opinion—life flowed: in discotheques. Practically all of my exhibitions were held in discotheques. Of course, there was no art system there was no catalogue, there was no gallery owner, there was no customer that came to see if there was anything new. As a result much of my work is lost. But it is not important to me, because I have expressed myself. I don’t expect recognition for that stuff.” -

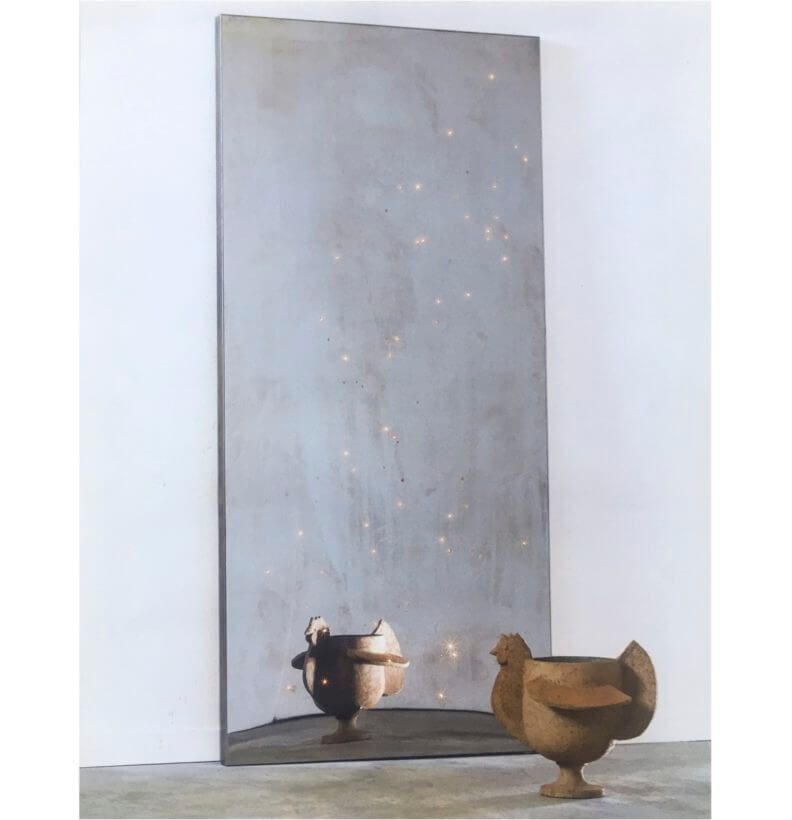

'Virtuale' publicity picture, 1970s, Artcurial.

'Virtuale' publicity picture, 1970s, Artcurial.

-

What triggered you to create lamps?

“One day I took one of my paintings and glued it onto a plywood table, and I started to make some holes in them. Then I put some light bulbs at the back, from where they shone their little light. With this invention I went to a furniture shop and asked: ‘I make this kind of work, could this be of any interest to you?’ Furniture shops towards the end of the 1960s were fairly avant garde places. They were forming what we nowadays call Italian design, things that were never seen before, chromed things, shiny surfaces, et cetera.”“It was a very beautiful shop, and this gentleman, Italo Meroni, who was a very intelligent person, said: ‘This is very beautiful work, but it is too small. You need to make it much bigger.’ I went home and I got the idea to make Virtuale from a steel plate standard 1 meter by 2 meter, because it was produced in these dimensions. I made holes in the plate, put the light bulbs in, and I had invented Virtuale.”

-

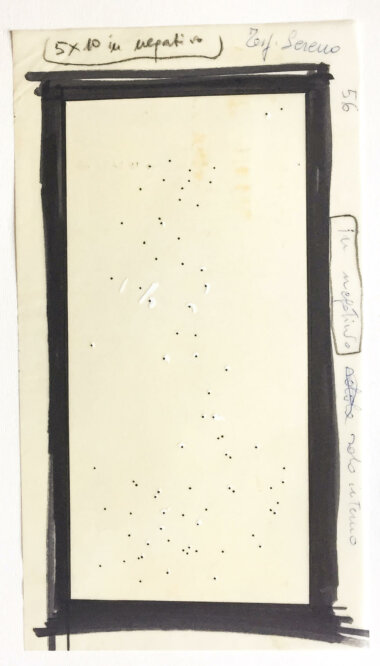

'Virtuale' drawing (source: Fulvio Ferrari).

'Virtuale' drawing (source: Fulvio Ferrari).

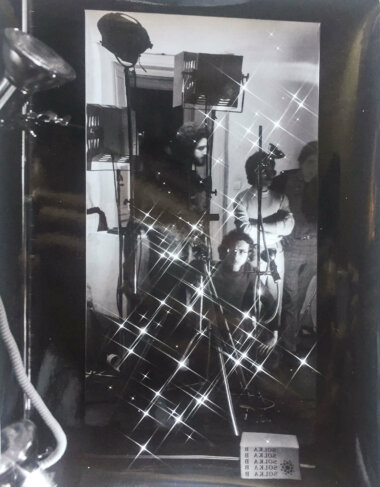

A photographic team in a studio reflected in 'Virtuale', picture by Studio Tede.

A photographic team in a studio reflected in 'Virtuale', picture by Studio Tede.

-

And from this moment on you started Solka B?

“This was not part of the company yet. I continued to work as a chemist. At this point I began to sell industrial chemicals, so I was a commercial employee. In this role I was able put my nose in all types of industries.““Seeing all these companies I learned about plastics, I went to see and ask about chrome plating. One day I met Beniamino Fassetta who made the wheel caps for the Volkswagen Beetle. A chromed form, that reflects all that is around. I liked it a lot, this possibility. I asked him if I could have one of the wheel caps, and then I asked my father to make a hole in the middle, and after that I had a lamp holder soldered under it. It was handcrafted in a very artisan way. It cost nothing, though.“

-

'Ameba', original publicity picture, 1970s, picture by F. Ferrari.

'Ameba', original publicity picture, 1970s, picture by F. Ferrari.

'Ameba' on the wall in Fulvio Ferrari’s home in Turin (source: Palainco).

'Ameba' on the wall in Fulvio Ferrari’s home in Turin (source: Palainco).

-

“One Saturday morning I went around some very beautiful stores of contemporary furnishings that do not exist anymore and I sold—I don’t remember the exact amount—but let’s say thirty-six lamps! And I had only one in my hand… So on Monday morning I resigned from my job and I started to make lamps.”

What did you do next?

“Of course I needed to make other models. The second lamp was Capacio. It was a spotlight, a stem, very simple, made of chromed metal with pincers from the chemical laboratory, which allowed you to position the spotlight in every direction. You send the light where you want it to go to, a very functional lamp.” -

‘Capacio’ floor lamp, original Solka B publicity pictures by Giulio Tua (left and right).

‘Capacio’ floor lamp, original Solka B publicity pictures by Giulio Tua (left and right).

-

“More than a design, again, I put things together. Capacio had the switch from the Fiat 500, because I didn’t try to achieve the design of a perfect lamp where I myself designed everything. This switch was very beautiful, so I used it.”

“I was not unique in this sense, when Achille Castiglioni made his lamp, Toio, the cord was held by the little rings of a fishing rod. So he also used something that he had seen around. Castiglioni was a of course a genius in design, and he made an impeccable, perfect lamp. Mine, if you want, was not in the same way refined, but it was a beautiful vision, people liked it a lot.”

“So this thing was successful, and thus I continued to design other models and other things to expand my company. With this lamp I started to have a real but very small business, but the shop owners whom I sold to belonged more to the avant garde and they liked it a lot, the completely new aesthetics with which I designed.”

“What helped me greatly, in the meantime, was my ability to sell objects having done a commercial job in a big company. I also understood —I don’t know how— that I should sell to the most important shops. To give importance to my lamps in a city like Turin I sold to one shop only, or at the most to two shops. In general, I sold my lamps in all provincial capitals, one shop in Bologna, one in Venice, and always the most beautiful ones. And so my lamps were sold in the most important places.”

-

Molecola (Picture by F. Ferrari).

Molecola (Picture by F. Ferrari).

-

What is the story behind Molecola?

“It was born exactly when Gino Sarfatti did the illumination for the Teatro Regio (in Turin) and without me knowing anything we both used the same invention in lighting technology, based more or less on the same intuition. He used prisms made of plexiglass, in the middle of which are the light bulbs. The light is reflected through the prisms and we see a cloud of light, lots of dots.

Mine was a bundle of tubes made of glass, inside there are micro light bulbs and the light of course was reflected, more or less in the same way. My lamp was much less sophisticated, Sarfatti was a fantastic designer who designed around 1000 lamps in his life, and produced them, while mine in fact was more of a vision, close to a vision of art, rather than a functional object.” -

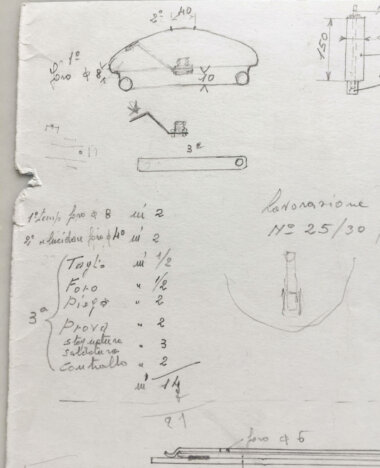

Drawing of ‘Molecola’ table lamp for Solka B, 1971 (source: Fulvio Ferrari).

Drawing of ‘Molecola’ table lamp for Solka B, 1971 (source: Fulvio Ferrari).

Of course it didn’t give a lot of light, but that was great, because it was a perfect lamp for the garçonnière, and at the time there was a big market for these places where people rented something for the girlfriend of the moment. And at the time it was popular to have brown painted walls in the living room, where even with 10.000 Watt it still seemed dark. The lighting object signalled a presence, set a boundary. A thing with many colours that was also very beautiful, a bit strange, because you did not understand from where this light came out.”

“This was one of the first lamps made in Italy with optical fibers. Nobody even knew what they were. I bought them at a company in Florence. I made two of these lamps”.

-

Where are they now?

“Who knows… It was very complicated to produce, and it was very expensive. My lamps were fairly expensive anyway. Virtuale, at the time, cost 225.000 Lire, half the price of a Fiat 500. So it was also not easy to sell a big number, but that was also not what I wanted, since I did not want to have an organisation, because I had understood very well that if you put in place an organisation you will be a slave of that organisation.” -

Solka B letterhead, 1970s. Design: Giulio Tua.

Solka B letterhead, 1970s. Design: Giulio Tua.

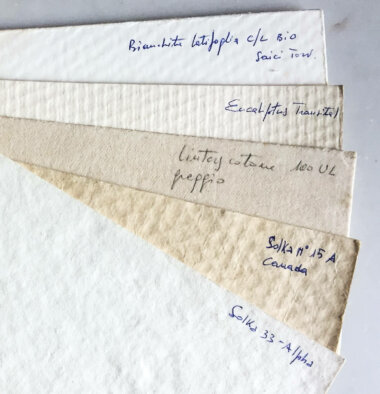

Swatches of cellulose used in the paper mill where Ferrari worked, among which 'Solka A’. 'Solka B', after which his company was named, was lost (source: Fulvio Ferrari).

Swatches of cellulose used in the paper mill where Ferrari worked, among which 'Solka A’. 'Solka B', after which his company was named, was lost (source: Fulvio Ferrari).

-

How many people did you work with?

“Three or four people who maybe came for half a day. I never had any real employees, so I had a tram driver that came in the morning or in the afternoon to mount lamps, and a student who came almost every day, he worked as a warehouseman. And there was a very kind man who was a welder at Fiat. And there was the wife of an immigrant from the south. She was ecstatic to work in this environment, for them it was something they had never seen before. It was very nice, it was work of course, but the atmosphere was like at the bar, because I never wanted a real business.” -

‘Girottola’ table lamp by Fulvio Ferrari for Solka B, 1971. Picture by Giulio Tua.

‘Girottola’ table lamp by Fulvio Ferrari for Solka B, 1971. Picture by Giulio Tua.

-

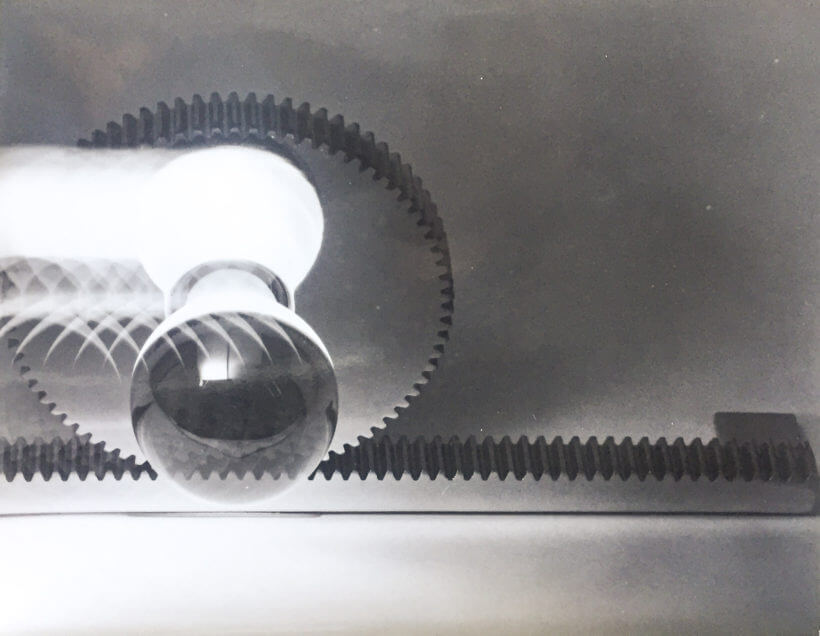

Then there was Girottola, another extraordinary model…

“The idea was to have an industrial object. It was a stick made of chromed metal, toothed, that is used in companies for a printing machine for instance, for a cart that needs to make a precise movement with a cogwheel. The bar lies on a table or desk, you can move the cogwheel back and forth. There is a light bulb in the centre exactly like I did with Ameba. -

‘Riccio’, table or wall lamp by Fulvio Ferrari for Solka B (1971). Picture by Giulio Tua.

‘Riccio’, table or wall lamp by Fulvio Ferrari for Solka B (1971). Picture by Giulio Tua.

Have you ever been interviewed about Solka B before?

“No. But sometimes people ask me a question because I composed the book ‘Luce’ (red. ‘Luce: Lampade 1968-1973: il nuovo design italiano, by Fulvio Ferrari and Napoleone Ferrari, Allemandi & C., 2003) which included some of my lamps. But apart from that nobody even knows that this company once existed. Before the book nobody knew what these lamps were when they appeared at auction houses.”For how many years did you have Solka B?

“I think for about 5 years. “How did the end of Solka B come about?

“I sold the company to a conglomerate of companies that operated in the home business. The owner knew me, and he naturally thought that I was very skilled. I called him and over the phone we decided that the company was sold.”

-

“I went away without passing on my knowledge. They found the catalogue with the lamps and they continued to produce. But nobody invented a new lamp, so obviously after a while they closed down. “

Why did you sell?

“My son was born, and Turin was very polluted, I didn’t want my son to grow up in a place like that. So I thought I would sell the company and go to Liguria. I had studied chemistry in Liguria, so I knew some people there.”Would you otherwise have continued?

“On the one hand I liked to create new things, on the other side I was a bit worried because I could not go on in the same way. I had to have an office where somebody made drawings. Because if I bought four mechanisms and one of them should turn out to be wrong, I could buy another. But if somebody would make them especially for me and they would turn out wrong, whose fault is it? It was necessary to have a structure, to have a real company.“ -

Sketch of ‘Ameba’ made by Gino Ferrari, Fulvio Ferrari’s father.

Sketch of ‘Ameba’ made by Gino Ferrari, Fulvio Ferrari’s father.

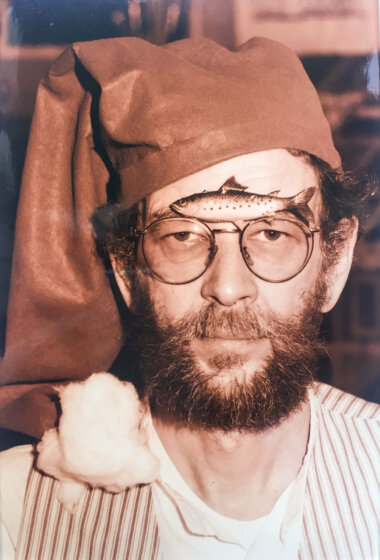

Fulvio Ferrari, 1970s (source: Fulvio Ferrari).

Fulvio Ferrari, 1970s (source: Fulvio Ferrari).

-

“It was a very interesting period, because I was in an avant garde place, things went ahead because they actually had a content. People saw these objects in a glass case and said: ‘Fantastic, I have never seen this before’. To be able to live these years full of creativity and seeing others like Castiglioni, Sottsass, and getting to know the process of manufacturing was very beautiful. “

Which of your lamps lamp do you like most?

“If today I had to save one lamp, I would save Molecola, because it’s the most imaginative lamp and immediately afterwards I would save Virtuale, but Molecola was one of the objects that was most representative of the desire to live in a space that was a little magical in essence.”So you created a little magic with everyday objects?

“I have to say yes, because also in chemistry things happen that seem magical. You put two things together and a green smoke comes out. Fireworks! It’s all chemistry…”If you would like to be the first to read articles on designers and special designs, please subscribe to our newsletter.

-

- Palainco wishes to thank: the brilliant and delightful Fulvio Ferrari for his gracious 'disponibilità'.

Unless otherwise stated, all material is sourced and/or generated internally. All rights reserved.

- Text: Palainco, Koos Logger & Ingrid Stadler.

- Image sources: Fulvio Ferrari & Palainco.

The article and its contents may not be copied or reproduced in any part or form without the prior written permission of the copyright holders.

Published on: 10 October 2017