“In my next life I will be an artist”- an interview with designer Carlo Nason

Magical forms in Murano glass

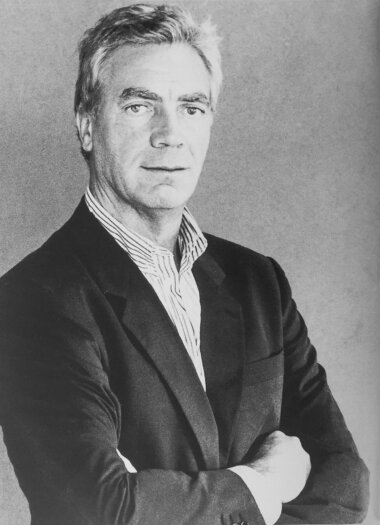

Carlo Nason is the creator of numerous extraordinary lighting pieces. Born in Murano in Italy, into a family of many generations of glass makers, he was destined to work with the material, though not in the traditional way. Always inspired by forms, Nason designed many objects—and of course lighting pieces—using the most refined Muranese glass techniques.

While many of Nason’s pieces were very successful, their creator maintained great privacy. Evi, his wonderfully supportive wife, helped us to secure an interview, for which we met in his studio. There, against his nature, he kindly let us lift a tip of the veil of his world. The following interview was translated from Italian.

-

Main picture: Carlo Nason in his studio (source: Palainco); This picture: The entrance to Carlo Nason's studio (source: Palainco).

Main picture: Carlo Nason in his studio (source: Palainco); This picture: The entrance to Carlo Nason's studio (source: Palainco).

-

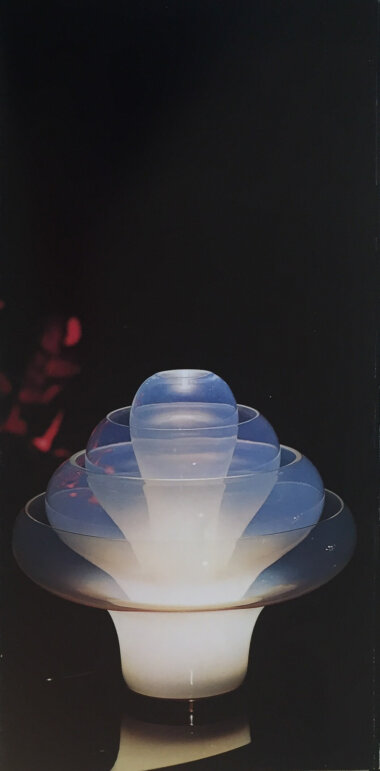

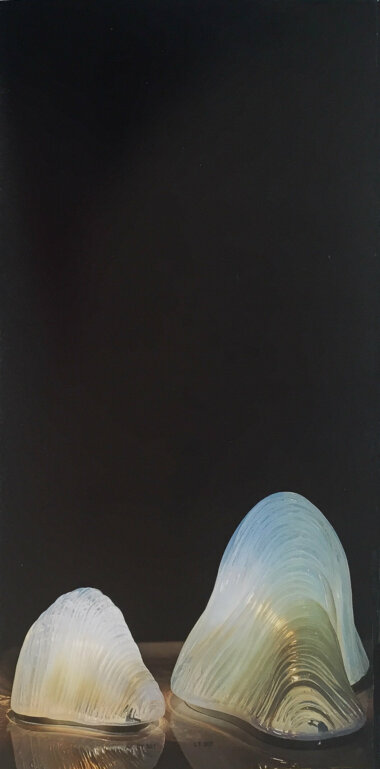

LT 305 table lamp, designed by Carlo Nason for A.V. Mazzega (picture by Carlo Nason).

LT 305 table lamp, designed by Carlo Nason for A.V. Mazzega (picture by Carlo Nason).

Do you remember the first time you went to see how glass was made?

“When I was small, together with my father I lit the first ovens [of V. Nason &C.] with a match. I was maybe ten years old. At the time, they didn’t have gas, they used coal or wood, and later naphtha. That was how the ovens, the vetrerie [glass factories] worked. They were dirty with oil, etcetera. I remember that my father’s first glass factory worked on coal.”

Was it expected of you to start working in the family business once you had finished school?

“It was easy to do so, because at the time the factory was next to the house. The family was involved in the vetreria, so it was easy to follow the production. I always went in, also when I studied ragioneria [accounting]. And the vetreria itself was like family at the time. You didn’t know where the vetreria ended and where the family started.

When I was young and went to school, the glass from Murano did not interest me much. I always had the idea of the form, of forms. When I was young I remember my father taking me to Milan, to La Rinascente and to the fairs. I bought Japanese vases made of metal, because I liked very simple and smooth forms. I maybe started from there.”

-

La Rinascente department store in Milan: Grandi manifestazioni, “Il Giappone”, 1956 (source: Archivio Amneris Latis, Milano).

La Rinascente department store in Milan: Grandi manifestazioni, “Il Giappone”, 1956 (source: Archivio Amneris Latis, Milano).

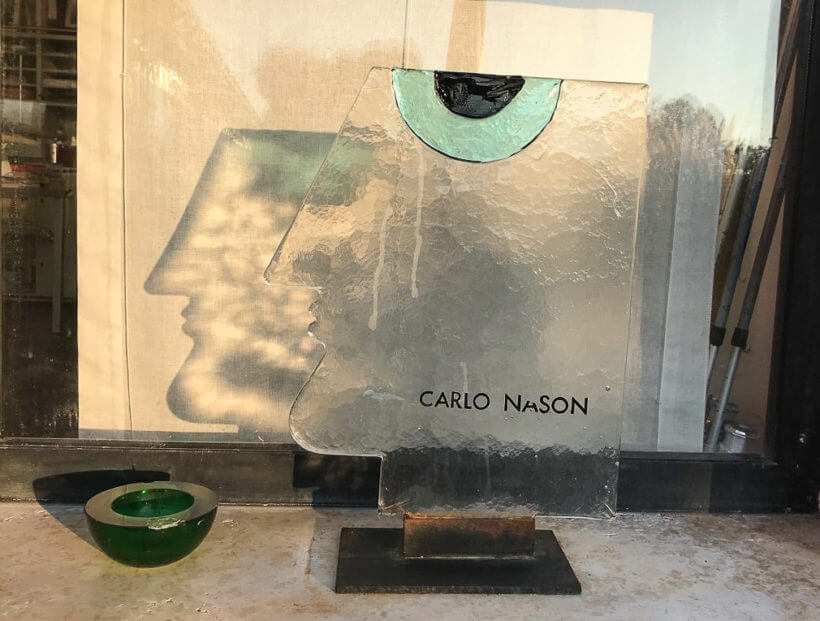

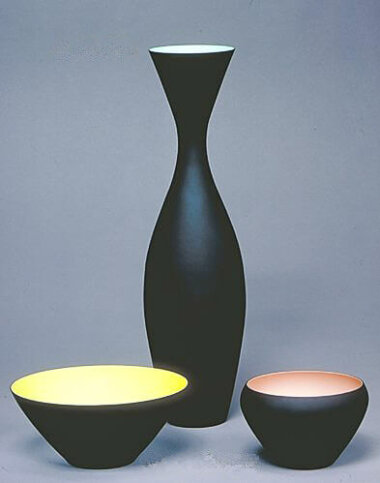

Vases designed by Carlo Nason for V. Nason &C., Corning Museum of Glass, New York (source: Corning Museum of Glass).

Vases designed by Carlo Nason for V. Nason &C., Corning Museum of Glass, New York (source: Corning Museum of Glass).

-

Did you also work in that period?

“I always had these ideas to design, so I started to make things. I started to work in 1955. I was around eighteen years old when I designed vases that were produced and sold, and in 1959 the Corning Museum [in New York] included them in their collection. They ascribed it to V. Nason &C., but it was my design.

After that I continued to design, but at V. Nason & C. there were not many possibilities to make these things. I had in mind to produce modern lamps in glass, so I went to Mazzega [A.V. Mazzega]. Gianni Mazzega was a friend of the family. With them I tried to make lamps, as I wanted to make a catalogue. In the vetreria at the time they did things for the American market: ashtrays, vases in big series, nothing special. And I was busy trying to make these lamps. A client of Mazzega, a big producer of furniture, liked them. He had a line of lamps himself. He said: ‘You should make them for me’—but in the end I made them for Mazzega. So they opened the road for me, the vetreria, to do tests of all kinds and to make handblown lamps.”

-

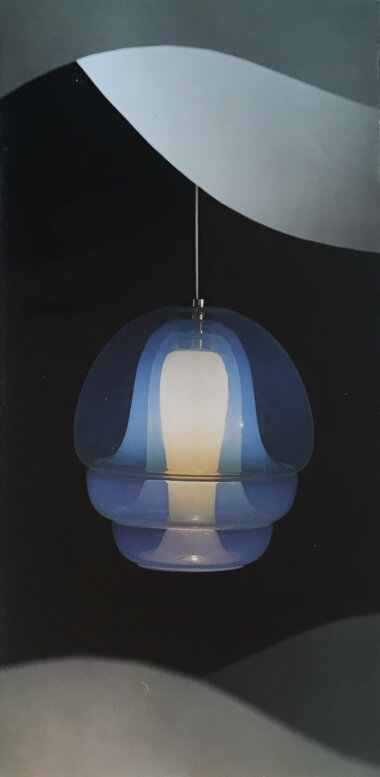

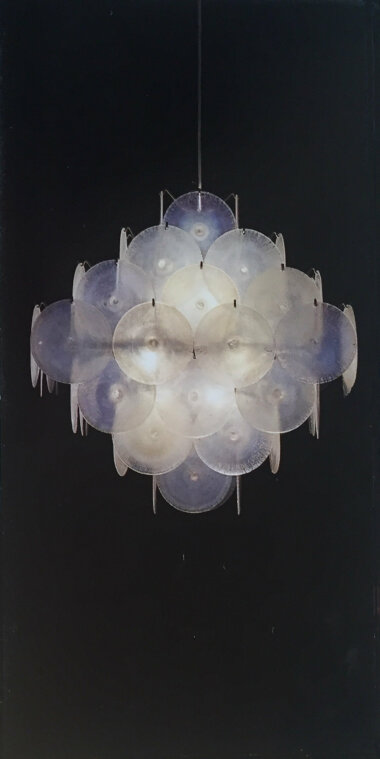

LS 134 pendant in opaline blown glass, designed by Carlo Nason for A.V. Mazzega (picture by Carlo Nason).

LS 134 pendant in opaline blown glass, designed by Carlo Nason for A.V. Mazzega (picture by Carlo Nason).

In that period you were fascinated by layers of glass?

“I made several things like that, I don’t know why… Maybe it was easy for me to make these things with Mazzega. There was this possibility. For me it was not difficult to make lamps with all these layers. They gave me the possibility and I gave it a try…”

Would you say it has become your style?

“Maybe.“

It is very recognisable, and maybe nobody else did the same?

“Not with many glass pieces. It’s easy to find a lamp made of only one glass. Maybe it was because of the possibility that I had with Mazzega to express myself in the most free way… This lamp for example, whether it cost a thousand or ten thousand euros, I did not think about it. And also Mazzega did not think about it. He thought about making something new, something different. I worked as a designer from the outside, or as an independent designer, but I was the only one there. Mazzega gave me the possibility to do everything that I wanted to try, to throw away if it did not work out, to hand-blow, not to hand-blow…”

-

Carlo Nason (picture by Neno Brusegan).

Carlo Nason (picture by Neno Brusegan).

LS 120 pendant in opaline blown glass, designed by Carlo Nason for A.V. Mazzega (picture by Carlo Nason).

LS 120 pendant in opaline blown glass, designed by Carlo Nason for A.V. Mazzega (picture by Carlo Nason).

-

So when you really started to work, and started to do what you really wanted to do, you had the possibility to do whatever you wanted?

“Yes. In the beginning, when the first models turned out well, and they sold well, had a success, Mazzega gave me the space to do whatever I wanted. It was beautiful!”

Can we look at some models that you made for Mazzega?

Sitting in his studio we browse through Nason’s extensive collection of original catalogues. During his long career he worked for many other producers besides Mazzega, like I TRE, Murano Due and Kalmar.

“There are some models that had success, others had less success.”

This one, for example, model LS 120?

“This one was a big success, although it was very difficult to make. There were four glasses, you see…”

And this one, LS 134, is often called Medusa [jellyfish]?

“I don’t know what idea I had, maybe the glass gave me the idea, the glass in the middle… half transparent, not completely transparent. There are four soffiature [blown parts]. I made the form, then I had it blown, then had it cut and tested until it worked out well.”

It seems complicated to make?

“Yes, a bit complicated, but the effect was great. It was very successful, that lamp. Now it would be more difficult, it would cost a lot to make four pieces of glass for one lamp. At that time it was possible. “

And everything had to be very precise?

“Absolutely! The moulds were made of wood and they had a metal section where one part was supported by another. When the glass was blown into the wood it burnt a bit, but it was necessary to have the same circumference for all lamps. So there was always a piece of metal in the wooden mould, to keep them all the same. It was always complicated, in short.

Many forms needed a mould, into which the maestro blew the glass. So I went to the workshop, where they were made, and I said: ‘Can you make it like this?’ Sometimes I learnt a lesson, I got to know how they worked the wood, how they worked the glass, what they could and what they could not do.

When I had an idea, I made little sketches, I experimented to see if it was worthwhile continuing. If it was interesting, we could try something with glass. Anyhow, I always did a lot of tests for a model.”

And so by experimenting…?

“Exactly. Many experiments died, because it was not possible to continue.

I remember that once we had to do a fair in Milano. We tried with the maestro to make a lamp, he had added a decoration and a beautiful lamp came out. We presented it as a model. But when we had to put it into production, we couldn’t make it again—at this, Nason laughs. The maestro couldn’t remember, he was not able to do it, and we cancelled the lamp.”

-

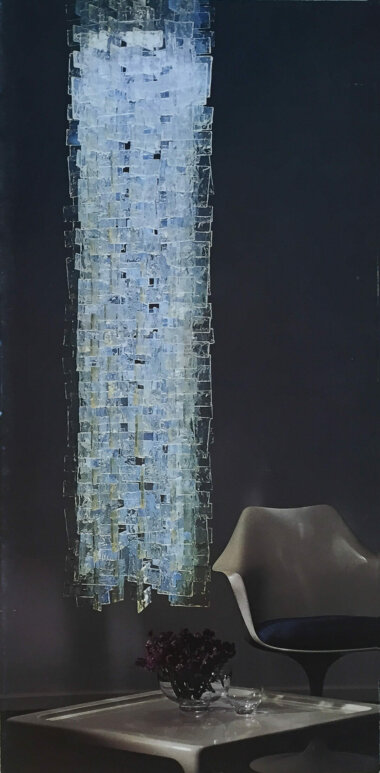

LS 150 and LS 151 pendants, with individual elements (or 'neck-ties') in crystal or opaline glass, designed by Carlo Nason for A.V. Mazzega (picture by Carlo Nason).

LS 150 and LS 151 pendants, with individual elements (or 'neck-ties') in crystal or opaline glass, designed by Carlo Nason for A.V. Mazzega (picture by Carlo Nason).

LS 170 pendant, consisting of 312 'hooks' in opaline glass, designed by Carlo Nason for A.V. Mazzega (picture by Carlo Nason).

LS 170 pendant, consisting of 312 'hooks' in opaline glass, designed by Carlo Nason for A.V. Mazzega (picture by Carlo Nason).

-

What did you say when you returned home when, for example, you had made the Medusa: ‘I made something wonderful?’

“No… I felt it when I made a good lamp, a beautiful lamp. I had the sensation that I had made something different.”

What did you think of the products that were made in Murano?

“I wasn’t too enthusiastic about them. Regarding illumination there weren’t many modern things in Murano, maybe there were none at all when I started to make certain things, to use certain glass types, the hooks, the piastra [plate], etcetera. I found it interesting to work with colature; they poured the glass on metal, the plate, and so it was possible to make these kinds of shapes. I did a bit of everything, some things went well, others not very well.”

-

LT 301 and LT 302 table lamps in opaline glass, designed by Carlo Nason for A.V. Mazzega (picture by Carlo Nason).

LT 301 and LT 302 table lamps in opaline glass, designed by Carlo Nason for A.V. Mazzega (picture by Carlo Nason).

How did you get the idea for the Iceberg table lamp?

“Who knows… “, he laughs, “They were blown.”

But how did you obtain that surface…?

“The glass was blown into a mould completely made of metal. It was all made by little metal sheets that circled all around the mould—Nason starts to draw—like this. They blew the glass inside, between one sheet and the other went the glass, but it was all a bit irregular, not too even… It came out like this. I also made vases this way.

Ideas undoubtedly come from emotions, also from the moment in which you live, what happens around you. Maybe you have an idea when you see something that has nothing to do with a lamp, but which comes from a form. And you think it over in your head, and like that… Often it happened in the vetreria that maybe a maestro or a ragazzo [apprentice] did something for himself, a little something, una stupidata, and from there maybe later there could pop out something different. This also happened at Mazzega.

-

I was always in the vetreria, also with my father, I saw them trying to make things. I didn’t learn at some school, I learned in the vetreria. And that is important, because you know what result you can obtain, and what you can’t do. And then, who knows… Trying new things, all the hand-blowing that I did with Mazzega, the opaline etcetera, was important.

Sometimes at Mazzega, when an architect from Milan arrived and the maestri and workers liked him, they succeeded in making certain things. However, if they disliked him because he was arrogant, they tried, but said: ‘It’s not possible, it doesn’t work.’

-

LS 132 pendant, consisting of discs in iridescent crystal, designed by Carlo Nason for A.V. Mazzega (picture by Carlo Nason).

LS 132 pendant, consisting of discs in iridescent crystal, designed by Carlo Nason for A.V. Mazzega (picture by Carlo Nason).

The discs were very successful, and also this one, the cravatte [neck ties], LS 153… This one was very successful, LS 173, this one…, this one… And also this one (LT 305) that you, Palainco, also have.

The discs also cannot be made anymore. They were produced in crystal, made as a soffiatura [blown piece] and then opened and etched, burnt with an acid that is not permitted anymore. They turned opaque like this, a bit fluorescent, but it is not possible anymore to make them now. I tried to have them made, many times, but they didn’t turn out like they used to.”

Did you have to make a certain number of models?

“No, the quantity per year was not defined. But I made a lot anyhow. I liked to make things, I liked to try things. Some of them turned out well, others less so, but anyhow I made a lot.”

-

What does Murano mean to you, what has it been like for you to live here?

“It was not always easy, but it was possible to move around. I did all the fairs in Milan, a few with Mazzega, a few with others, I went to see the Salone del Mobile, I stayed informed about what was happening around me. “

So you were free in your mind? You didn’t feel that you had to remain here?

“I went to Milan, maybe once a week, once every ten days, because I needed to see the things that they did over there. Here the atmosphere was a bit classic, the old Murano.”

We already talked about innovation, that you always wanted to find new ways?

“I very much liked the form, modern forms. When I went to Milan, I was immediately interested in different forms, modern forms, very simple ones, Japanese ones… I wasn’t very interested in the decorated Murano glass, all the things with the decorations and colours. In fact, I used very few colours and decorations. I always looked for the clean form.”

-

LT 315 and LT 316 floor lamps in white sfumato glass, designed by Carlo Nason for A.V. Mazzega (picture by Carlo Nason).

LT 315 and LT 316 floor lamps in white sfumato glass, designed by Carlo Nason for A.V. Mazzega (picture by Carlo Nason).

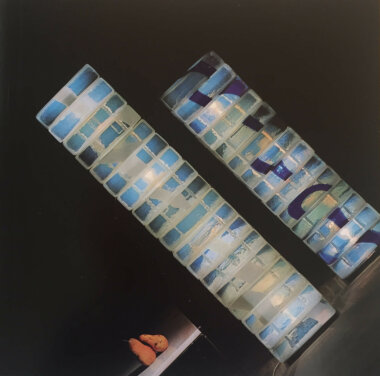

LT 313 and LT 314 floor lamps in opaline glass with white stripe and blue stripe, designed by Carlo Nason for A.V. Mazzega (picture by Carlo Nason).

LT 313 and LT 314 floor lamps in opaline glass with white stripe and blue stripe, designed by Carlo Nason for A.V. Mazzega (picture by Carlo Nason).

-

LT 220 floor lamp designed by Carlo Nason for A.V. Mazzega (picture by Carlo Nason).

LT 220 floor lamp designed by Carlo Nason for A.V. Mazzega (picture by Carlo Nason).

In your opinion, which of your models are the most innovative?

“There are always those models that, in my opinion, were different from others, that were new. Also to use a certain type of glass, to use those big soffiature, one inside the other. Very often I did things not only with one piece of glass, but with two or three pieces of glass. I don’t know, but that was what interested me. The right glass to make these different thicknesses was this glass that is transparent, but a bit opaque, opaline. It went very well and so maybe with this idea of superimposing various layers of glass, this type of glass was ideal. Maybe that’s why certain lamps were born, just because of the type of glass.

I did a lot at Mazzega and then I stopped working there, because I started to work for I TRE and Murano Due, a group of people. We were friends and they said: ‘Come work for me,’ so I worked for them. They were Venetians, but they had a large operation in Murano. I did a lot for them. I’ve got sketches of lamps that have not been executed, I’ve got ideas in abundance for table lamps, wall lamps, all kinds of lamps, and other things.”

-

So you still get ideas?

“Now and then, yes, but there needs to be a reason. If there is a reason you can have ideas, but it is no good when nobody cares.

You know, even now I study forms—Nason shows us some models. These I made for vases, a bit strange, handblown, so often I dedicate myself to making forms out of cardboard to see the effect. This one remained here. Nothing was made out of it, but it could be done. These could be ceramic vases; I always tried to make things that were different. “

-

Carlo Nason at home (source: Palainco).

Carlo Nason at home (source: Palainco).

-

Do you see yourself more as a designer or an artist?

“As a designer, but it would have been better to be an artist and to have made a few pieces, say, ten important pieces. However, I always made things that sold thousands of pieces. I always had to accept what the industry said, the factory. If they said: ‘No, we can’t do this, we did calculations and in the end it would cost too much, we can’t sell this lamp,’ then I had to cancel the idea. That is how the designer works. Being a designer also means that you need to think about which producer you approach, because many can do certain things, others can do other things. That is what being a designer is about. Instead when I’m an artist I only think of myself, to make a sculpture, to make ten of them and to sell them to galleries. However, since I was a designer things ended when they were not successful. It depended on the model, the money, the sales. That’s how it works for a designer, unfortunately.”

But in the beginning maybe you did not think a lot about these things and you did the things that you liked?

“Exactly, but I never made works of art, important things. I always wanted to make things that I liked, little things, like lamps. And they sold. Unfortunately, that was how it was. Maybe I should have been an artist.”

In your next life?

“In my next life I will be an artist.”

If you would like to be the first to read articles on designers and special designs, please subscribe to our newsletter.

-

- Palainco wishes to thank : Carlo and Evi Nason, for their very kind cooperation and warm hospitality.

Unless otherwise stated, all material is sourced and/or generated internally. All rights reserved.

- Text: Palainco, Koos Logger & Ingrid Stadler.

- Image sources: Carlo Nason, Corning Museum of Glass, Neno Brusegan, Archivio Amneris Latis and Palainco.

The article and its contents may not be copied or reproduced in any part or form without the prior written permission of the copyright holders.

Published on: 9 July 2019